Knowledge warriors

Meet six Los Alamos National Laboratory employees who strive to educate the public and stakeholders about the Lab’s work.

- Whitney Spivey, Editor

Los Alamos scientists thrive on discovery—but they’re sustained by knowledge. These six “knowledge warriors” help keep that knowledge alive, preserving Los Alamos National Laboratory’s legacy and advancing its national security mission.

Alan Carr; senior historian

“Science is not imperceptible to the public, but it’s often spoken in a language most people have not learned,” says Alan Carr. “As a historian, I strive to make our scientific history accessible—and even exciting—to broad audiences.”

Carr, who has worked at Los Alamos National Laboratory since 2003, doesn’t aim to persuade audiences about how past events unfolded. Instead, he seeks to create accurate, engaging portrayals of history that educate and inspire. Recovering forgotten stories is a bonus. “Few things are more satisfying than discovering an elusive fragment from the past that helps us better understand our present,” he says.

For Carr, acquiring new information is an opportunity to grow as a historian. “Embrace opportunities to revise your understanding,” he advises. “Consider unfamiliar possibilities and perspectives. Expect surprises. Treasure feedback. Never be afraid to ask questions or admit, ‘I don’t know.’ And never stop listening.”

Carr frequently lectures at the Laboratory and is a familiar voice in local and national media, as well as at historical conferences and panels across the country. An expert on Manhattan Project and Cold War history, he’s also known for his engaging presentation style—marked by a subtle Texas accent, sharp wit, and rich multimedia that brings his stories to life. “The past is multidimensional,” he says. “Our interpretation of it should be, too.”

Regardless of audience or venue, Carr’s goal remains the same: to illuminate the Laboratory’s history to inspire the future. “Over the past 80 years, Los Alamos has built a nearly unmatched legacy of technical innovation and discovery,” he says. “Remembering our scientific lineage can help create an even greater future.” ★

Jonathan Creel; program manager, Manhattan Project National Historical Park

Many Manhattan Project structures were built hastily and with little documentation. Eighty years later, Jonathan Creel, the Lab’s program manager for the Los Alamos branch of Manhattan Project National Historical Park, is responsible for preserving those fragile buildings—and for helping the public experience them.

Maintaining authenticity while ensuring safety is a balancing act. “These buildings have to be free of hazards like asbestos and rodents, but they also need to look and feel as they did in the 1940s,” Creel says. “I want people to step into these spaces and feel like they are actually stepping back in time to the Manhattan Project.”

That sense of history is palpable at places like the Slotin Building, where physicist Louis Slotin suffered a fatal criticality accident in 1946. “The building’s period of significance is less than a fraction of a second,” Creel notes, “but that moment forever changed how the Laboratory operates.”

Getting the details right is sometimes a challenge. “We’re trying to solve problems that no other preservation professionals have to solve,” Creel says. “For example, no one else is trying to replicate the spark-resistant Hubbellite flooring that was used in high-explosives facilities.” The solution, he adds, is surprisingly simple: red paint mixed with sand.

Because the park sites are on restricted Laboratory property, public access is limited. Some structures—such as the Slotin Building—can be visited during guided tours offered through a lottery system. In 2025, more than 3,000 people vied for just 180 tour spots. Since the release of Oppenheimer, “people are flying in from all over the country for a four-hour tour—which most of them say feels too short,” Creel says. “We aren’t likely to make the tours longer, but every year we do manage to give more tours to more people.”

During tours, Creel likes to emphasize the creativeness and resourcefulness of the Manhattan Project scientists. “When they realized that high explosives melt like chocolate, they called major candy companies—and that’s why we have two giant candy kettles out at V-Site,” he says. “Kettles like these were used to make the explosive lenses for the Trinity Gadget and the Fat Man bomb. That kind of ingenuity is really fascinating to me.” ★

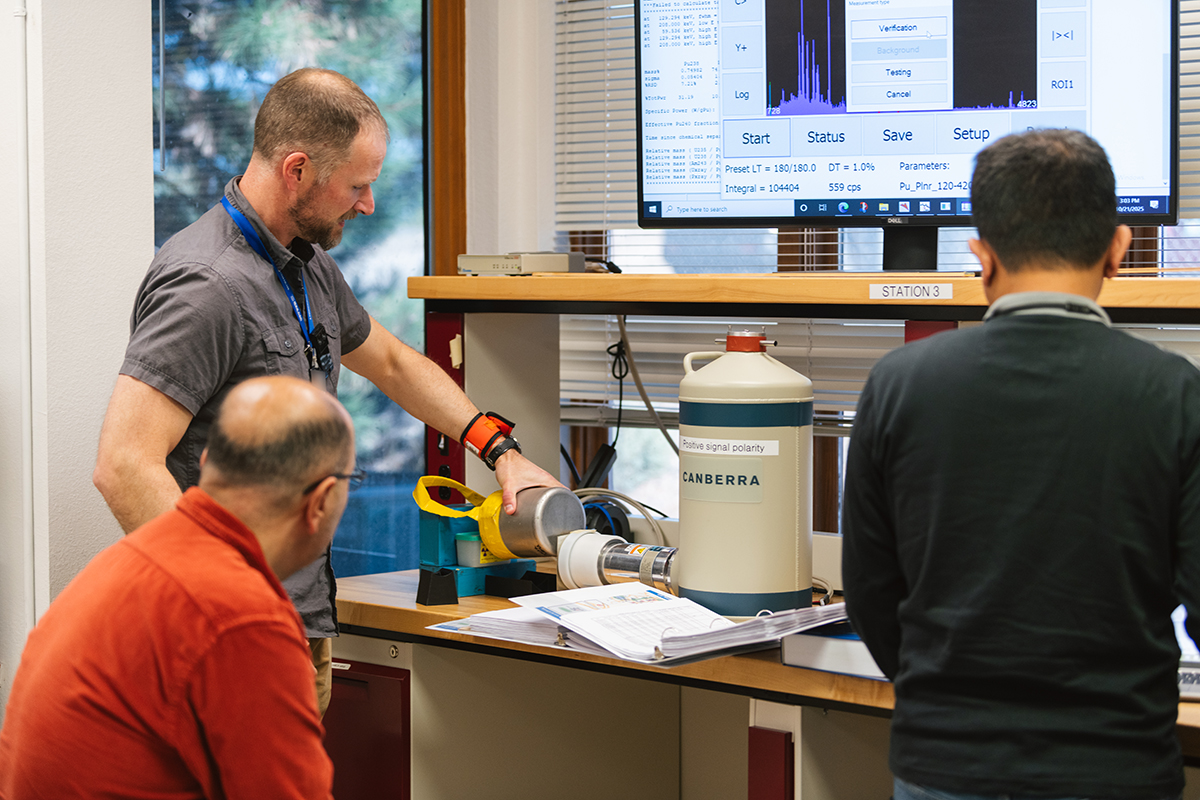

Tim Goorley; chief scientist for nuclear weapons effects

Some days, Tim Goorley feels like a movie critic. “I talk a lot about what people see in the movies: Terminator, Alien, Wolverine, and now Mission Impossible 8,” he explains. “I point out that Hollywood gets it wrong all the time—those effects are simply too big.”

Goorley is talking about weapons effects—what happens when a nuclear weapon detonates. His audiences are often members of the military: potential users of nuclear weapons who are not necessarily technical experts. “Effects are sometimes difficult to explain,” Goorley says. “So I try to relate scientific quantities to things most people can grasp—like the pressure you feel at the bottom of a pool, the pain of a second-degree sunburn, or the force of the wind on your hand when you stick it out of a car window going 100 miles per hour.”

To help make those concepts even more tangible, Goorley often turns to the Lab’s nuclear testing video archives, always mindful of classification limits. “They say a photo is worth a thousand words,” he notes. “Well, a movie is worth a thousand photos. And a complicated Mach stem—when a shock wave and its reflection merge—captured on film is priceless.”

When communicating with any audience, Goorley’s goal is to serve as a trusted source—someone who can provide accurate, unbiased information about weapons effects, regardless of which laboratory (Los Alamos or Lawrence Livermore) designed the weapon. “I’m weapon-agnostic,” he says. “I don’t advocate for Los Alamos over Livermore. I’m just the guy who can tell you what a particular detonation will do.”

Goorley acknowledges that discussions of weapons effects can be polarizing. “When I talk to people—especially members of the public—I try to be mindful and respectful of their experiences,” he says. “Someone might be a Hiroshima or Nagasaki survivor. Someone might have lived downwind of the Trinity test. We should never deny people their experiences or emotions. Sometimes we’re called to go beyond science and engage on a human level.” ★

Paula Knepper; deputy director, Center for National Security and International Studies

The Center for National Security and International Studies helps connect Los Alamos science and technology with the broader policy and strategy conversations that shape national and global security. “As the Center’s deputy director, much of my work involves translation between disciplines,” says Paula Knepper. “I help scientists understand what policymakers need, and I help policy audiences grasp the scientific and technical foundations of national security.”

During her 30 years at Los Alamos, Knepper has seen those conversations evolve. “A decade ago, discussions centered more on legacy nuclear issues—stockpile stewardship, nonproliferation, arms control, and deterrence,” she explains. “Those topics remain vital, but today’s audiences are equally focused on emerging technologies such as AI, biothreats, and cyber.”

Whether she’s hosting an interactive workshop or mentoring new employees, Knepper focuses on context. “Even when the details of our work can’t be shared publicly, the why almost always can,” she says. “Framing science in terms of its national purpose—whether that’s safety, deterrence, nonproliferation, emerging technologies, or crisis decision-making—helps audiences see the relevance of what we do.”

Equally important, she says, is connection. “Connection is how we invest in knowledge itself,” Knepper explains. “In a world of increasing polarization and misinformation, building understanding around national security science is both an act of service and an act of stewardship.”

For Knepper, sharing knowledge is essential to the Laboratory’s mission. “Knowledge doesn’t serve its purpose if it stays locked within institutional walls or remains accessible only to experts,” she says. “It needs to flow, to be passed forward. That’s especially true in national security, where today’s emerging challenges will be tomorrow’s crises. The next generation of leaders needs both the technical foundation and the contextual wisdom to navigate them effectively. Strengthening the bridge between knowledge and trust is how we ensure the Lab’s expertise continues to serve the nation for generations to come.” ★

Anna Llobet; scientist, director of the Summer Physics Camp, member of the Oppenheimer Memorial Committee

Experimental physicist Anna Llobet believes that science belongs to all. “It’s important that we bring the love and thrill of knowledge to everyone,” she says.

To that end, Llobet founded the Summer Physics Camp, a two-week program that introduces students from New Mexico and Hawaii to careers in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). The camp blends hands-on experimentation with mentorship from scientists across the Laboratory—an approach that has inspired many participants to pursue STEM degrees.

In 2023, Llobet was elected vice-chair of the J. Robert Oppenheimer Memorial Committee, which honors the Lab’s first director by promoting science education and preserving his legacy. The physics camp and the committee share a common goal: to make science accessible and relevant to people of all backgrounds. “Science and technology have brought longevity to humanity,” she says. “But for science to guide public policy and shape our future, society must first trust it from an educated standpoint.”

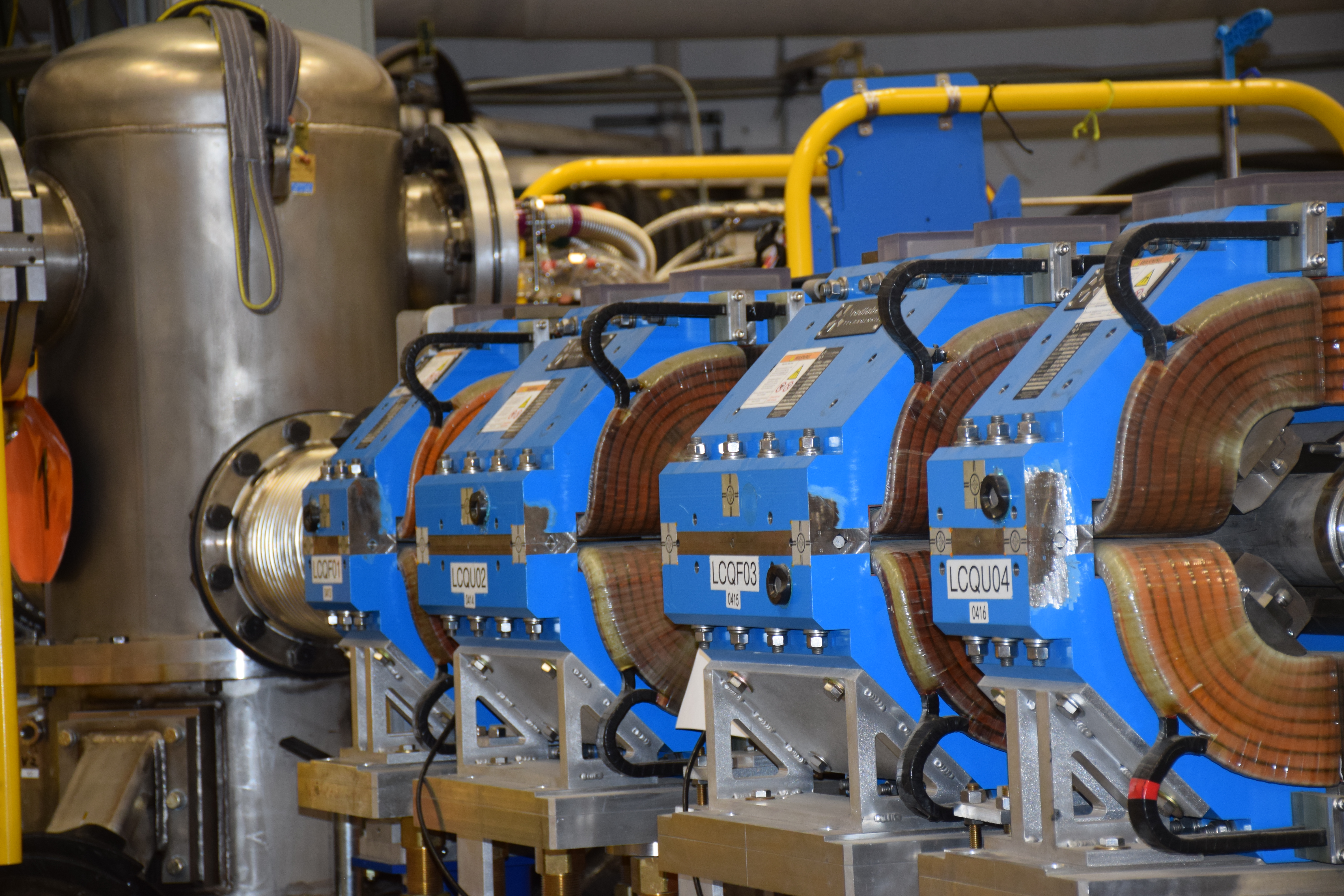

Originally from Barcelona, Spain, Llobet joined Los Alamos as a postdoctoral researcher in 2001. Her career has evolved from materials science and neutron scattering to shock physics—the study of how materials behave under extreme pressure. At the Los Alamos Neutron Science Center, she conducts experiments that, combined with supercomputing simulations, help ensure the safety and reliability of the nation’s nuclear deterrent.

After more than two decades at the Lab, she feels deeply connected to both her colleagues and her community. “Very few of us were born and raised here, but after 22 years, they’re my family away from home,” she says. “This town and the Laboratory are amazing spaces where knowledge and creativity feed one another,” she adds. “As a scientist and as a person, I want to contribute to my community, to society, and to the world’s future—and that’s exactly what working here allows me to do.” ★

Patrick Moore; director, Bradbury Science Museum

As a kid growing up in Los Alamos, Patrick Moore and his family often took visitors to the Laboratory’s Bradbury Science Museum. Back then, the unclassified museum was located at the Lab’s main technical area, its entrance flanked by replicas of Fat Man and Little Boy.

Some 40 years later—after a career spanning research, historic interpretation, and preservation at organizations including NASA, the National Park Service, the U.S. Navy, and the Smithsonian Institution—Moore returned home as the Bradbury’s director. His mission is to inspire the next generation of Los Alamos kids and visitors to the small mountain town.

“I make a point of taking time each day to engage with the public,” says Moore, noting that the museum, now located in downtown Los Alamos, welcomes up to 70,000 visitors annually. He’s observed a shift in recent years. “For a long time, the museum primarily attracted people who already had a connection to the Lab,” he explains. “Now, since Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer movie, people are discovering Los Alamos for the first time—and coming here specifically to learn more.”

Moore also notes that today’s audiences are increasingly aware of global tensions and are curious about the Laboratory’s role in national security. In 2024, a new exhibit was installed to highlight the Lab’s contributions to stockpile stewardship. “The work we’re doing to maintain and advance the nation’s nuclear deterrent is just as important as the work done during World War II and every single day of the Cold War,” Moore says. “There’s a growing awareness of new adversaries, and the sense of discomfort that brings is precisely why our work matters.”

Educating visitors about the Lab’s mission can be complex—not only because of the breadth of research conducted at Los Alamos but also because visitors have different levels of knowledge and curiosity, as well as different learning styles. “Every visitor is important, and we have to meet them where they are—not where we want them to be,” Moore says. “At the Bradbury, we’re as cutting edge as the Laboratory itself.” ★