Challenges accepted

After eight years of obstacles, an experiment is successfully executed.

- Jill Gibson, Communications specialist

Murphy’s Law states that anything that can go wrong, will go wrong. Although Murphy is often correct, a team of Los Alamos National Laboratory scientists, engineers, and technicians recently proved him wrong by overcoming eight years of challenges to execute an experiment—Hydrodynamic Test 3681—at the Lab’s Dual-Axis Radiographic Hydrodynamic Test (DARHT) facility.

“Eight years!” emphasizes Jennie Disterhaupt, the lead experimenter for the test. “Everybody had their opportunity to navigate difficult challenges.”

The experiment, which kicked off in 2017, faced numerous setbacks from the beginning. “People really rallied to work together against the odds,” Disterhaupt says. “We kept pushing, facing hard problems, and coming up with creative solutions to achieve great things.”

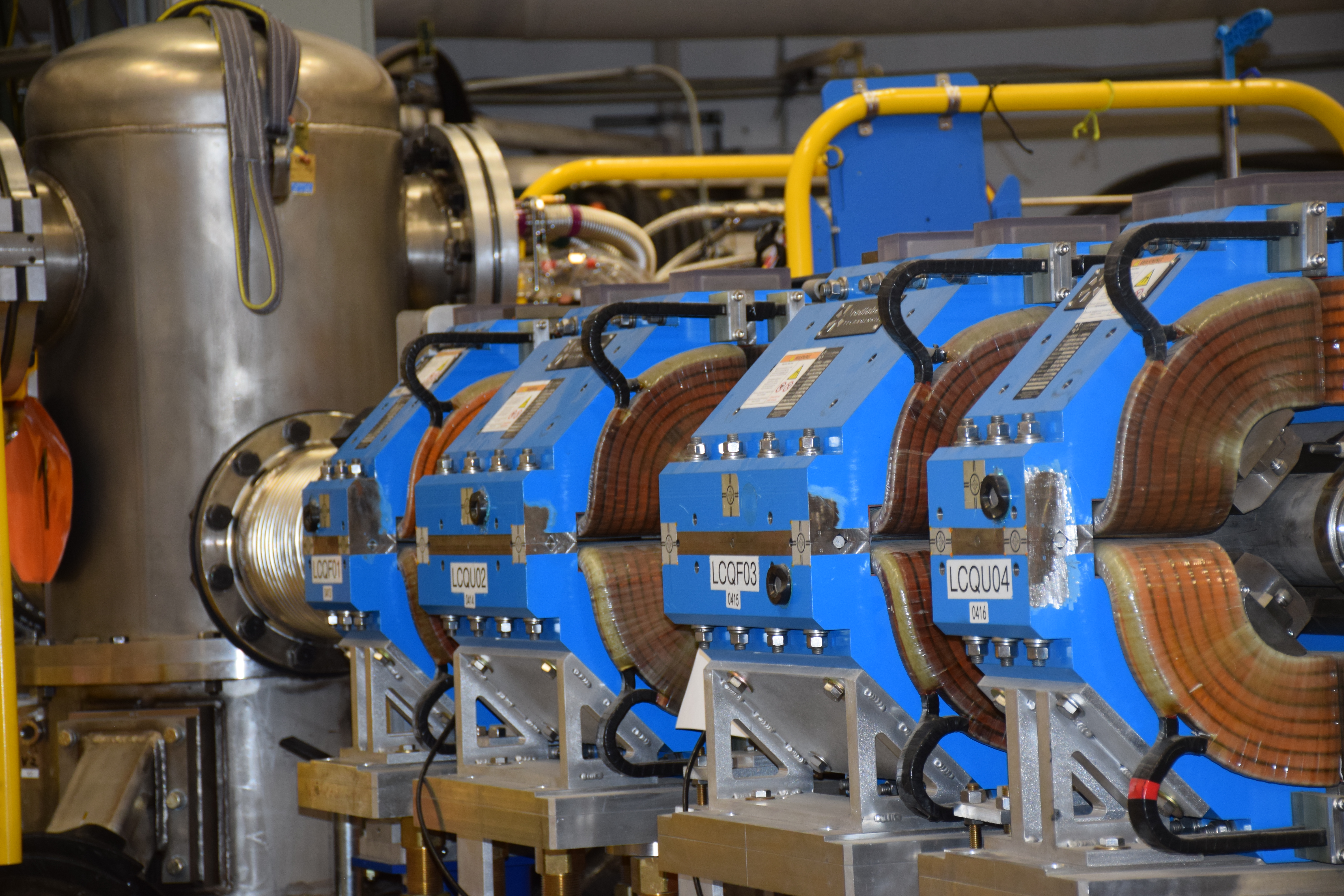

DARHT consists of two linear accelerators that intersect at right angles and create pulses of high-powered x-rays to produce radiographs (high-powered x-ray images) of mock nuclear weapons components detonating inside a steel containment vessel. In a real nuclear weapon, some of these components would be made with plutonium. In DARHT hydrotests, however, the components are made with a surrogate, non-plutonium metal. The implosion rapidly heats the surrogate to temperatures high enough to cause it to flow like water—which is why many DARHT tests are called hydrodynamic tests, or “hydrotests” for short. Hydrotests such as 3681 play a crucial role in conducting weapons research and ensuring the nation’s nuclear weapons are safe, secure, and reliable. But what happens when multiple things go wrong? Every experiment the Lab conducts at DARHT is challenging, but Hydrotest 3681 had extra issues to tackle, explains Disterhaupt.

The first challenge was one researchers across the country battled: the COVID-19 pandemic, which delayed the test. When researchers returned to a regular work schedule, they faced personnel turnover, design changes, fabrication issues, assembly issues, and other problems.

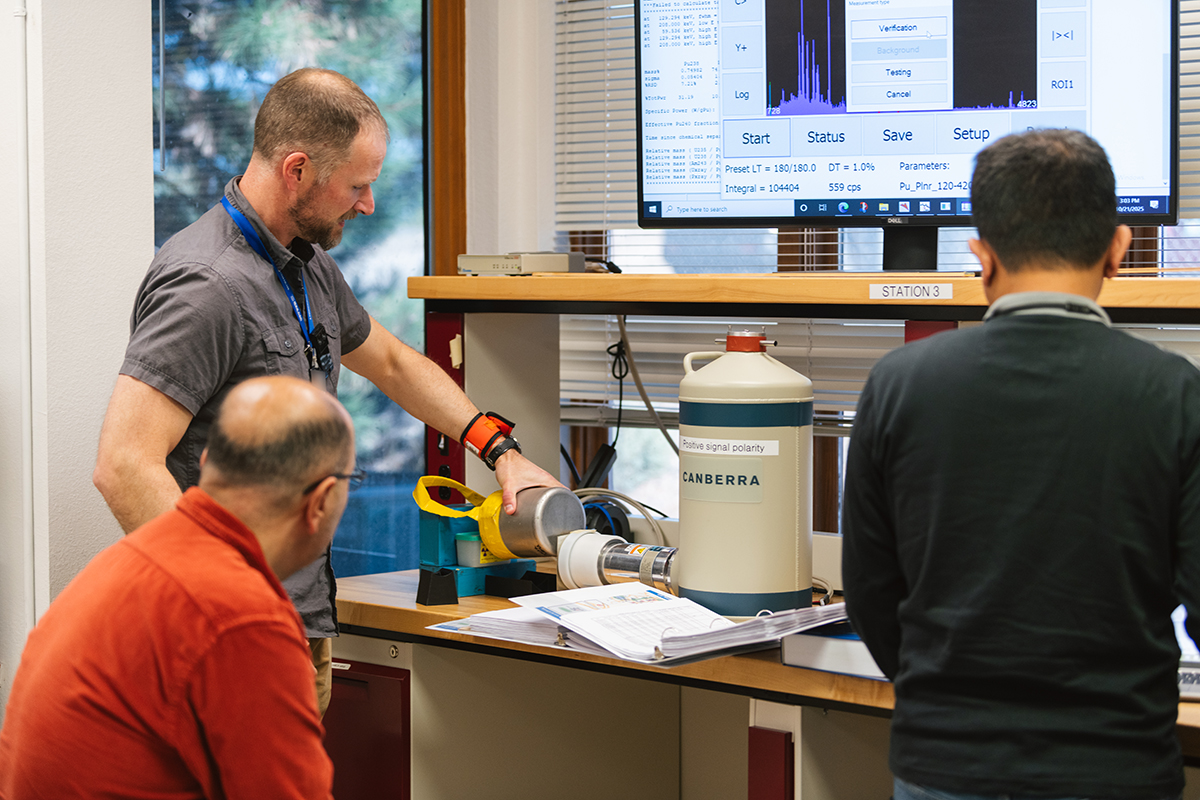

A second obstacle was the need to produce an extremely high-energy x-ray so scientists could “see” through what Disterhaupt describes as “a thick object.”

“We knew we would need to push the accelerator to produce an extremely high x-ray dose,” she says. Once again, Murphy’s Law came into play. From integrating maintenance and tuning of the machine to the loss of an accelerator cell and a camera that started showing signs of failure, difficulties continued to arise.

One teammate got extra kudos for his commitment, when the much-delayed test landed on the evening of his 30th birthday—on a Friday night to boot. “I definitely had to adjust my plans,” jokes Brian Esquibel, but he adds that he was eager to show up. “I’ve never worked on a project in my life that required this much tenacity.”

Hydrotest 3681 was also the first hydrotest to use optical initiation detonators to start the experiment. These detonators are triggered by laser power rather than electricity. Using optical initiation in the test was an unconventional effort, and the team had to jump through a lot of hoops to get results.

The use of laser technology to initiate high explosives is a major safety improvement, says CJ Benge, an engineer in the Detonation Science and Technology group.

“Traditional initiators are electrically driven, and with that comes the risks of static, lightning, or other electrical hazards,” Benge explains. “Optical initiation eliminates several of those hazards and acts as its own electrical standoff, drastically decreasing the risk of an electrical spark or discharge.”

The scientists also had to adjust their operational procedures for the new initiators. The form, fit, and function all had to align down to a billionth of a second—and they did.

Ultimately, Hydrotest 3681 returned much-needed data to ensure that the nation’s nuclear weapons remain safe, secure, and effective. Disterhaupt said the success was due to “hardworking people who are really good at what they do.”

Team members have already begun work on the next test for the system, which, according to Disterhaupt, they don’t expect to take eight years to complete. ★