Experts training experts

Los Alamos scientists teach international inspectors to identify nuclear material.

- Jill Gibson, Communications specialist

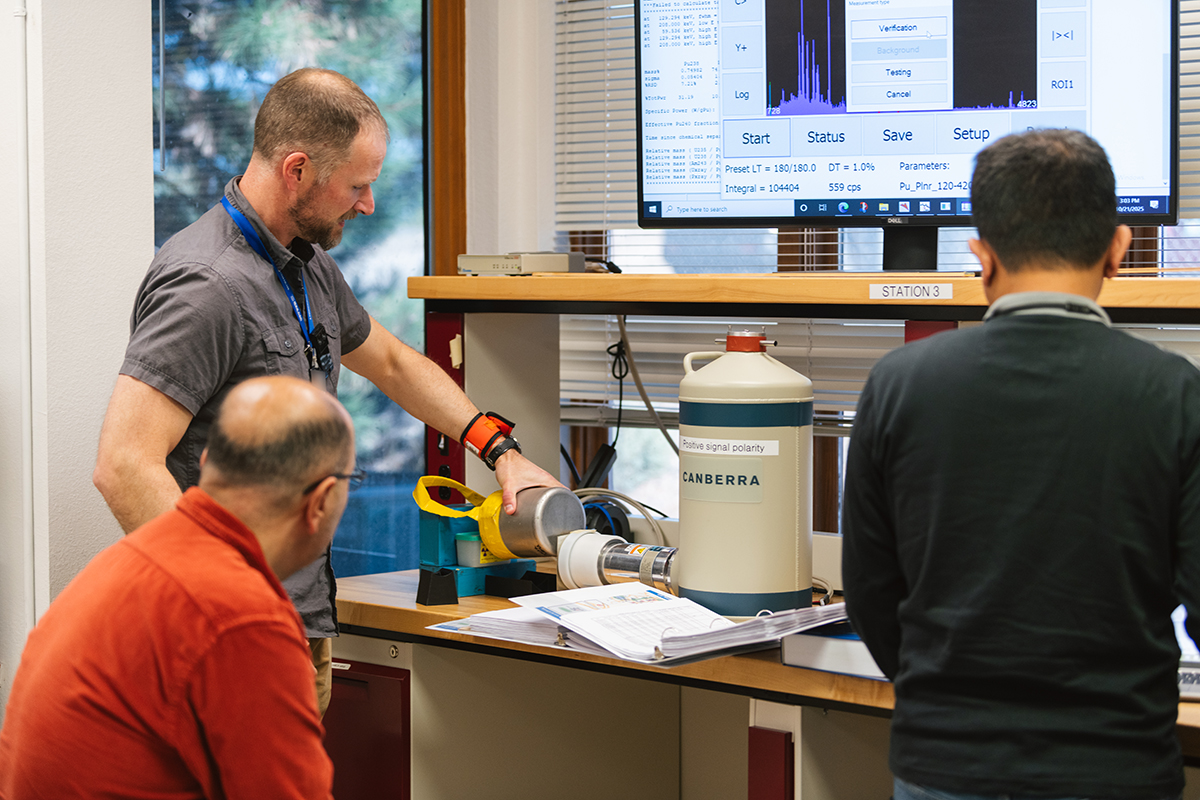

Los Alamos National Laboratory staff member Pete Karpius hands a small container to the group of people he is teaching. “See if you can figure out what’s inside,” he says. The container may—or may not—hold plutonium, a highly radioactive material that can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. The people in the class will use a specialized radiation detector to identify whether the sample inside the mystery container poses a risk.

This exercise is part of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspector training that Los Alamos has hosted for decades. Students come from across the globe to learn to use gamma-ray and neutron-based measurement techniques to determine the quantity and characteristics of nuclear materials—such as uranium, plutonium, and various associated isotopes—without altering or destroying the sample being measured. This approach is called nondestructive assay, and it’s a key part of how the IAEA verifies that countries are not misusing or concealing nuclear materials.

The IAEA is an autonomous international organization that works in close partnership with the United Nations. Headquartered in Vienna, Austria, the IAEA promotes the safe, secure, and peaceful use of nuclear technology. IAEA staff members travel to different countries to conduct inspections to verify that nuclear material and technology are not being used for nuclear weapons development. To learn how to do that, they turn to the experts at Los Alamos.

“This is a proud part of our Los Alamos legacy,” says Marc Ruch, the director of the Lab’s Safeguards and Security Technology training program. “Most of the tools and techniques that the inspectors use were developed here. Our trainers understand this stuff inside and out.”

Los Alamos offers both introductory and advanced courses so that the inspectors can practice measuring the kinds of nuclear materials they might encounter in the field, including depleted uranium, plutonium, and research reactor fuels. The training groups vary in size from about 10 to 25 people, and the classes are scheduled at the IAEA’s request. Each year, the Lab usually offers one introductory class that is required for all inspectors annually and a second, optional advanced class.

“The inspectors have a stressful role, and we aim to teach them to do the best job they possibly can,” says Karpius. He points to the image on the monitor displaying the readout from the mystery sample. This image is called a gamma-ray spectrum and is analogous to a fingerprint for the radionuclides inside. “This one is difficult to analyze,” he tells the students. “What would you do?”

Many of the IAEA inspectors in this advanced class have been in the field for several years and are eager to attend training. “These inspectors do an incredible job,” Ruch says. “It’s important for the people implementing nuclear safeguards to have a chance to go through a challenging measurement environment during training like this.”

The advanced class lasts two weeks, bringing people from around the world to Los Alamos. “I enjoy meeting inspectors from all over the world; they have a wide variety of backgrounds and perspectives,” says Katherine Schreiber, a Los Alamos physicist helping teach the current class.

“These inspectors ask a lot of questions and pick up information fast,” she says.“That’s important because the way they use this knowledge supports global security.” ★