Fetching for knowledge

A new tool uses artificial intelligence to make classified documents searchable.

- Jake Bartman, Communications specialist

In the 1940s, during the Manhattan Project, Project Y (what is today Los Alamos National Laboratory) began cataloguing the documents that its researchers created as they developed the world’s first nuclear weapons. In the eight decades since, the Laboratory has accumulated millions more weapon-related documents, which are today housed in the Laboratory’s National Security Research Center. Although these documents constitute an invaluable resource for weapons researchers and stakeholders, their sheer volume has created a challenge: how to access information efficiently.

Enter Terrier, a new tool that is leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) to sniff out relevant documents, helping weapons researchers and other stakeholders find the information they need. Originally intended to make data from diverse Laboratory data repositories accessible via a search-engine interface, Terrier has since evolved into a chat-based tool that is leveraging the use of AI in novel ways on Los Alamos’ classified network, streamlining a once-laborious processes and pointing toward future AI applications at the Laboratory.

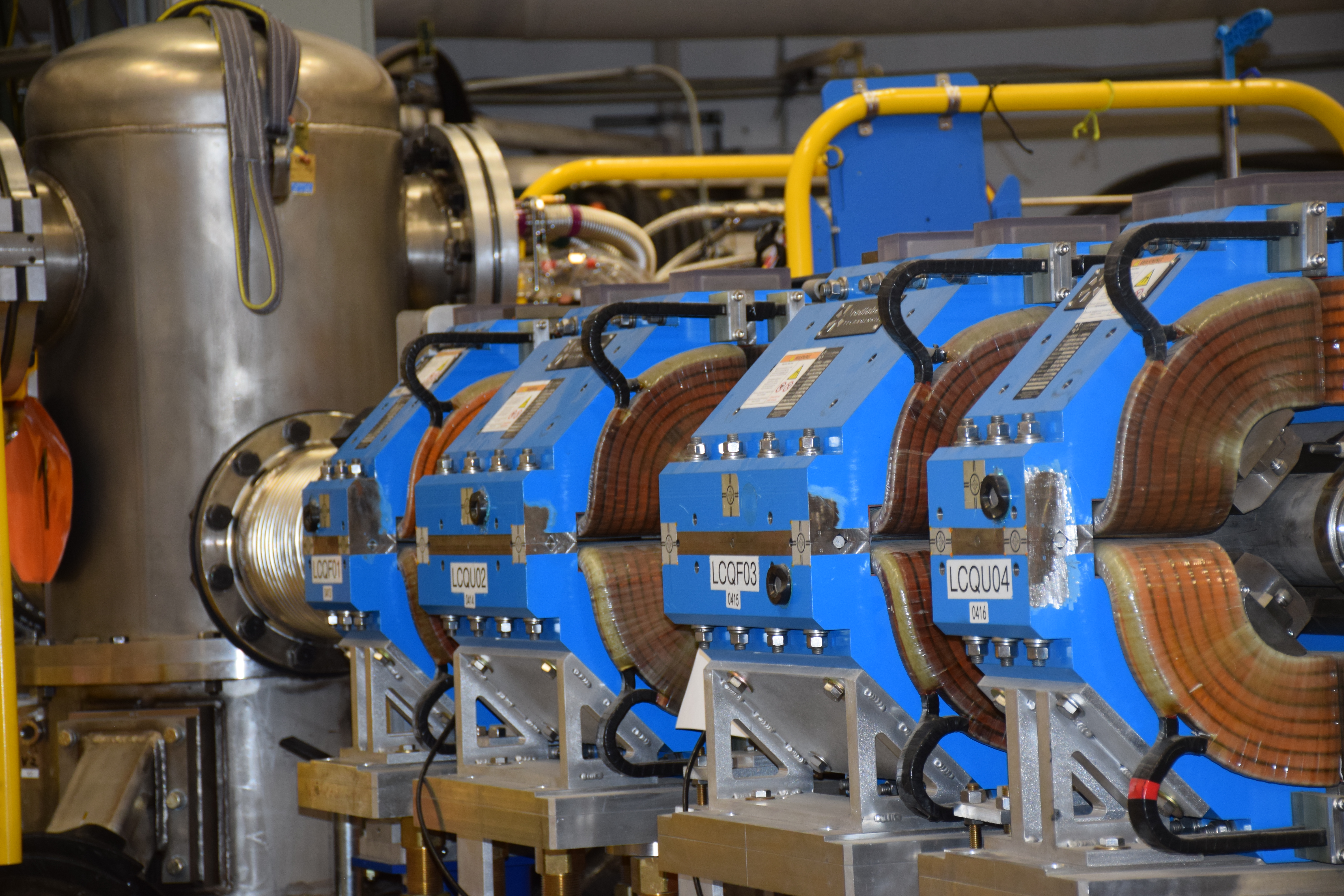

Terrier draws together data from multiple sources at Los Alamos, such as the National Security Data Solutions’ Online Vault and other shared drives that contain historic documents from the Laboratory, the (now closed) Rocky Flats Plant in Colorado (where the majority of plutonium pits—nuclear weapon cores—were manufactured), and more. To connect these previously siloed data repositories, Terrier relies on a knowledge graph—a schema that maps weapons-related concepts and terms in a way that computers can understand.

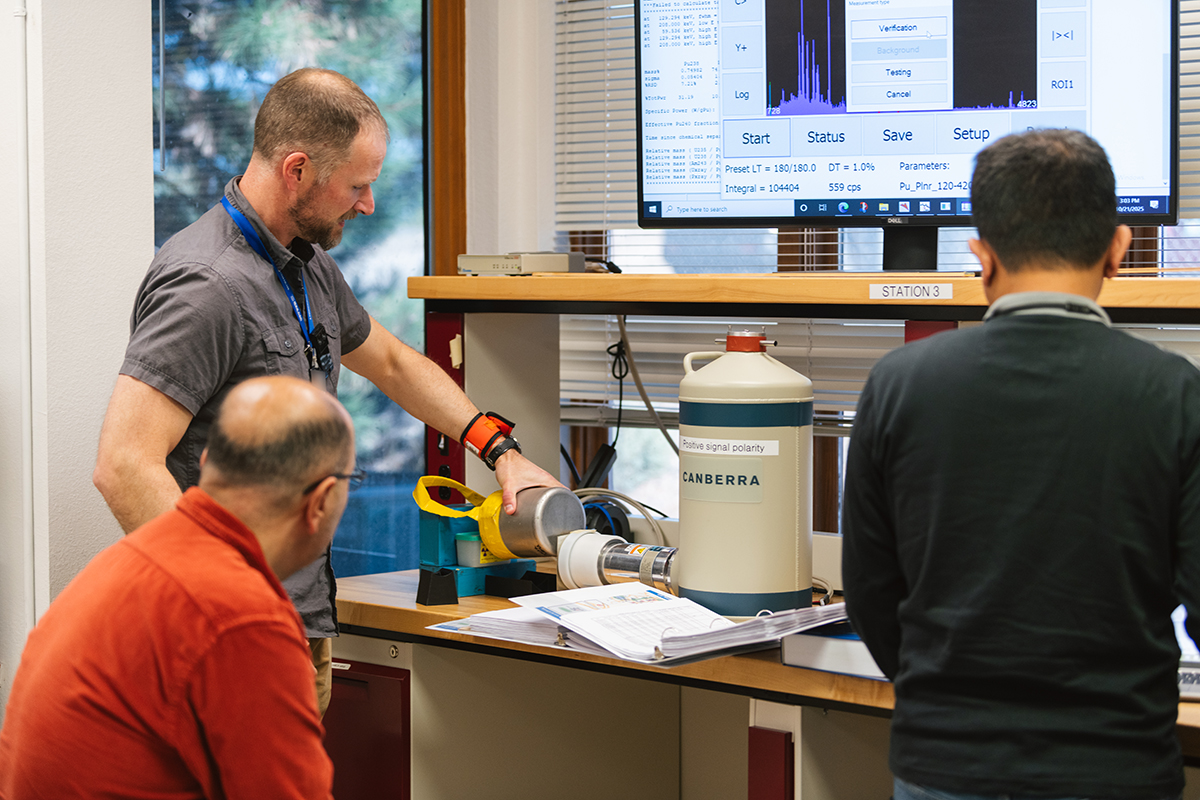

Initially, creating Terrier’s knowledge graph was a laborious process that involved interviewing weapons experts, identifying key weapons-related concepts, and charting the connections between these concepts in the knowledge graph. Then, individual documents could be catalogued and indexed to the knowledge graph.

Although these tasks could be completed by humans, the volume of documents meant that a more efficient approach involved using optical character recognition (OCR) tools (which translate hand- or typewritten documents into digital text) and transformers (which extract metadata from a document, capturing meaning in a numerical way). Yet the limits of older OCR tools meant that documents were often misread, leading to the extraction of inaccurate metadata, which in turn led to poorly indexed documents.

“Having humans curate the documents would be better,” says Tiffany Clendenin, who manages the Terrier program. “But we calculated that it would take a human something like 2,000 years to catalogue and index eight decades of documents—and that’s not considering the new material that the Laboratory is creating every day.”

AI has significantly accelerated Terrier’s work. In the past two years, Terrier began using new and improved OCR tools to re-scan and index documents. Next, Terrier deployed large language models to automatically summarize documents’ contents, identify keywords, and extract metadata, which can be incorporated into the knowledge graph and reviewed by weapons experts.

This approach is much faster than interviewing experts and then mapping their knowledge from scratch, says Jennifer Roos, Terrier’s technical project lead. “What I think is particularly exciting about what AI-machine learning is doing for us is that as it’s reading this data, it’s extracting so many keywords for us,” Roos says. “That information is so important to have.”

Large language models have also enabled a new interface for Terrier. Initially conceived as a natural language–processing search tool, Terrier is now designed to operate as a chatbot. Unlike chatbots such as ChatGPT, however, when a user enters a query about some aspect of weapons design or production, Terrier responds not with a generalized response written by AI, but with results from documents that address the query (an approach called retrieval-augmented generation). Users can then ask follow-up questions to expand or refine their query—a capability that enables knowledge discovery that goes beyond what would have been possible if Terrier had stuck with a traditional search-retrieval design.

Although new tools are helping Terrier achieve its mission, developing the technology has been challenging in part because of the constraints that come with working on the Laboratory’s classified network. A related obstacle involves ensuring that Terrier’s users have the appropriate clearance and need-to-know to access certain files. However, in the past year, the Terrier team has overcome these challenges and recently launched the Terrier chatbot at the Laboratory, allowing researchers to search more than two million documents. Additional repositories, which contain more documents, will be added to Terrier in the future.

“We have 80 years of information, and most of the people who created that information are no longer here,” Roos says. “These tools are allowing us to share all that information in a useful way.” ★