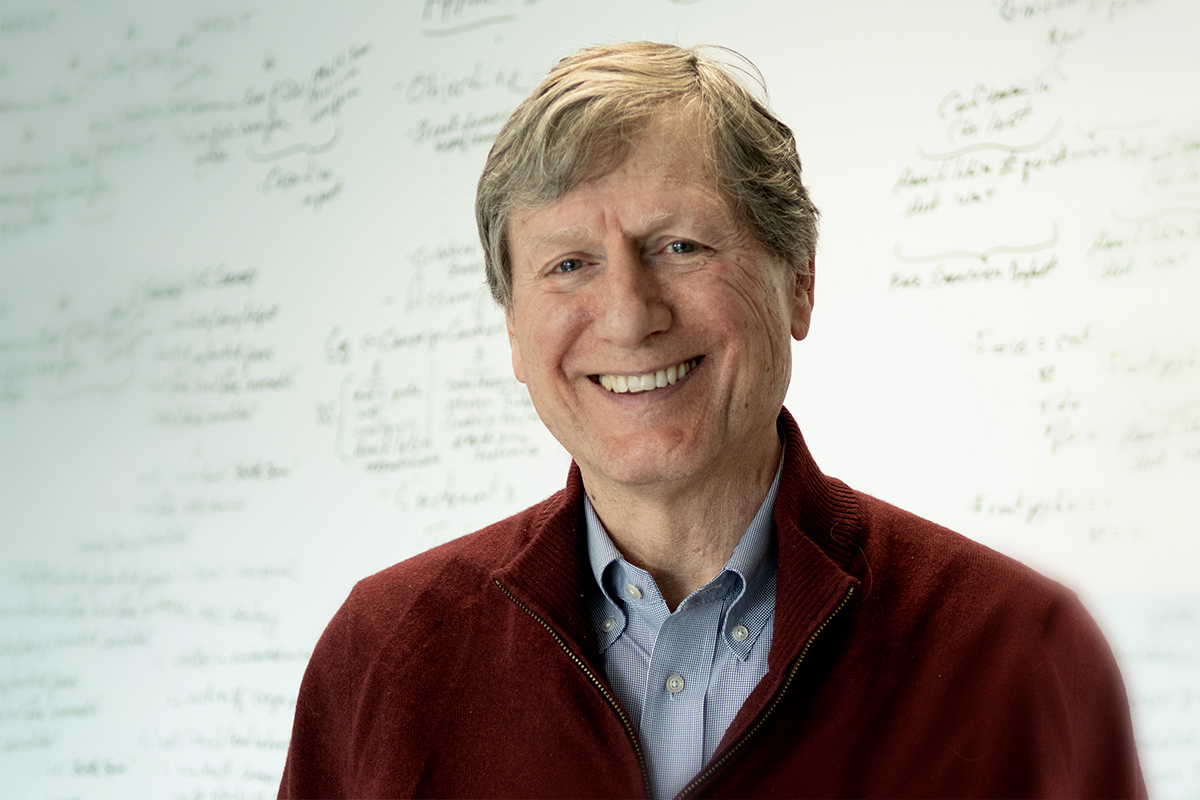

Happenstance, circumstance, and good luck

Steve Cambone, the former undersecretary of defense for intelligence who now leads Los Alamos National Laboratory’s Office of Strategic Assessment and System Analysis, reflects on a 40-year career at the intersection of defense, intelligence, and policy.

- Whitney Spivey, Editor

Shortly after Steve Cambone completed a Ph.D. in political science, a former schoolmate at Claremont Graduate School encouraged him to consider a job at Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. “I said, ‘that’s terrific’,” Cambone remembers. “And then I didn’t think very much more about it.”

The schoolmate called again a week later and asked, “Well, do you want a job or don’t you?” So, Cambone formally applied, interviewed, and in 1980 started in the Lab’s Strategic Assessment office, which was tasked by then-Laboratory Director Don Kerr with bringing a policy perspective to the Lab’s scientific and technical national security challenges.

Cambone went on to a successful career in private industry and the Department of Defense, eventually serving as special assistant to the Secretary of Defense, the Principal Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, and then as Director for Program Analysis and Evaluation. In March 2003, he was confirmed by the U.S. Senate as the first Undersecretary of Defense for Intelligence, a position he held through 2006.

In 2024, Cambone returned to Los Alamos to lead the Lab’s Office of Strategic Assessment and System Analysis, a new organization tasked with identifying, analyzing, and presenting options that leverage the Laboratory’s scientific and technical capabilities to shape and successfully implement national security programs.

Cambone sat down with National Security Science to reflect on his career, each step of which he says has been “a combination of happenstance, circumstance, and good luck.”

As a young adult, you considered teaching as a profession. Was there a certain point when you committed to a career in national security?

I think it was more of an evolution. Over time, beginning with my first job at Los Alamos, it became increasingly clear that I had an opportunity to make contributions in the national security space. As long as I was able to contribute, it was a career path worth pursuing.

As important, national security is an interesting and intellectually challenging field. I was advised once to never take a job that I didn’t find interesting. And I never did.

In certain respects, my work has never changed over 40 years. The positions differed, as did the responsibilities I was assigned. But in the end, I’ve been addressing similar issues from different seats. I truly have been privileged to hold each of the positions I have had.

In 2024, you returned to Los Alamos to lead the Office of Strategic Assessment and System Analysis (SASA). How did you make that decision after such a long career in Washington, D.C.?

In 2017, I was serving as an associate vice chancellor at Texas A&M University System (TAMUS). Subsequently, Texas A&M—along with the University of California and Battelle—was awarded the contract to operate the Lab. As a senior member of the TAMUS staff on campus with a clearance who had been in the nuclear, intelligence, and defense worlds, I was asked to serve on the Lab’s Mission Committee and traveled back and forth.

Those visits reminded me how much I enjoyed living in New Mexico and of the charms of Santa Fe. When COVID arrived, my wife and I relocated from College Station to Santa Fe. I continued to work for the university until early 2022 and then did some consulting work at the Lab. One day, I was invited to a meeting to discuss the establishment of what became SASA and asked if I would like to take part in standing it up? The work certainly met the criteria of being interesting, and I said yes immediately.

Has it been worth it? That’s best left to others to decide. Working with staff across the Lab, the SASA team has presented to Lab leaders insights they might not otherwise have had. If SASA continues to serve as a conduit for innovative thinking that leadership can appreciate and take action on, then I think it will have been judged a success.

What do you see as the Laboratory’s most important contributions to national security in the coming decade?

The Laboratory’s mission is clear: to assure that the weapons presently in the stockpile—and particularly those for which it is responsible—are properly maintained and are reliable, lending to the President the confidence that he needs to be able to manage the deterrence policies in the United States. That is our first challenge.

Second, the Laboratory will be asked to expand that mission to help in the development of new capabilities, which may entail new applications of what we’ve done in the past or doing something new. This requires that we think again about how we go about our work so that we’re confident that the President can be confident in what we deliver.

The strategic landscape is changing. The United States is likely to develop new capabilities and ways of thinking that strengthen our deterrent capabilities so that any potential adversary understands there is nothing to gain by challenging the United States.

How do you approach a new subject or begin to think about a new capability?

If you take time to listen to what’s being said and understand why it’s being said, you’ll find there is usually more to a subject. Think about what else might bear on that subject that the presenter either hasn’t thought about or that he or she knew but didn’t present.

Asking questions is as much for my own edification—please teach me more—as it is for helping a presenter to explore more deeply his or her own thinking on a subject.

Hardly anything that we do or create is without a reason. Knowing why something was, is, or should be done helps you decide whether to keep doing it or to make a change.

What advice do you give scientists and engineers at Los Alamos—and at other scientific institutions—about communicating effectively with policymakers?

Policymakers, particularly senior policymakers, are very busy people. Many and various things compete for their time and attention. To communicate effectively with them requires that we do our homework to understand what it is that concerns them and why it concerns them. What are the options they have in front of them to address what concerns them? Having done that, we can better assess whether those options include or should include insights that we here at Los Alamos can bring to them.

Senior policymakers know an awful lot. They don’t get to be in those positions without being quite accomplished. An indication of that accomplishment is their willingness to seek help in resolving hard problems. Using plain English when engaging them is the best approach.

What mindset do you think the next generation of scientists should develop to stay relevant to national defense?

Curiosity. If you’re not curious about your work, or about where your work fits in the mission, or where the mission fits into the national interest, it’s difficult to know how to arrange your thinking or how your thinking ought to be arranged to be of assistance.

The world is hardly a set place. Curiosity about it will lead you to discovering things that you never might have anticipated and could be quite influential in affecting. If you’re curious, you’ll get a reputation for being so—and that’s a good thing. ★