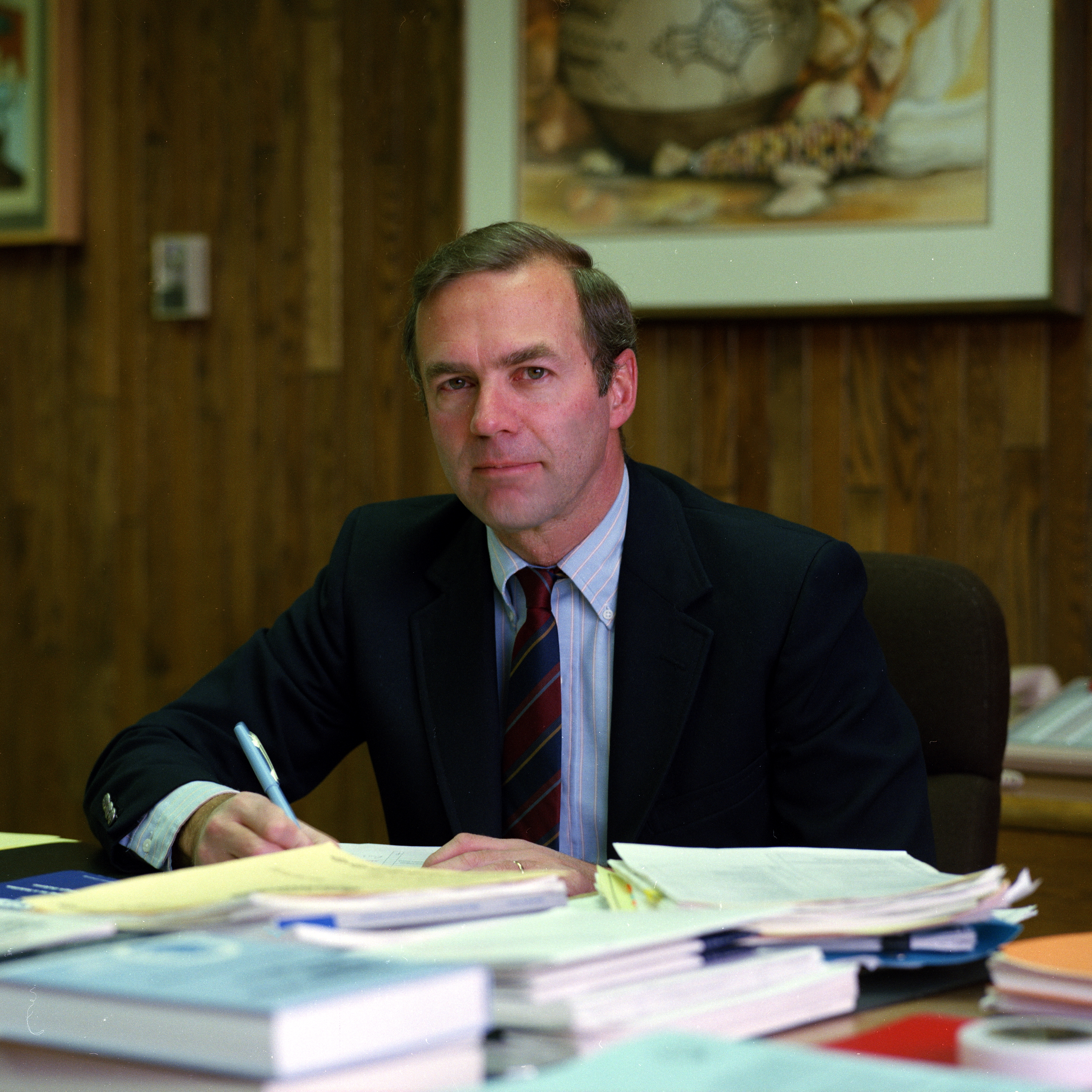

Don Kerr, scientist, public servant, leader

Remembering Los Alamos National Laboratory’s fourth director.

- Whitney Spivey, Editor

In 1966, 27-year-old Donald Kerr had just earned a doctorate in microwave electronics from Cornell University. Several of his advisors—including physicist Hans Bethe—had strong connections to Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. On their recommendation, Kerr accepted an offer to study ionospheric physics and its applications in high-altitude weapons effects. By that time, the Laboratory had conducted more than 500 nuclear tests and was deeply interested in how such detonations behaved in the atmosphere.

That year, Kerr, with his wife, Alison, their infant daughter, and their rottweiler puppy, drove cross-country from upstate New York to New Mexico, arriving in Los Alamos in July. “This was in the era of assigned housing,” Alison recalls. “We were assigned a place that was fine—except we shared it with a lot of cockroaches.”

Despite the unwanted roommates, Kerr thrived at the Laboratory. Alison notes that Don often traveled to support underground nuclear tests, including to the Nevada Test Site. He also visited Alaska to study auroras, which occur when charged particles from the sun collide with gases in the Earth’s atmosphere. “As an applied physicist,” Alison says, “he was into doing things.”

Bethe agreed, telling Science magazine in 1979 that Kerr was “a good experimental physicist, no question.”

Kerr also excelled as a manager. He was named a group leader in 1971, joined Director Harold Agnew’s office as an assistant in 1973, and became a division leader for alternative energy in 1975.

This rapid rise into leadership came as no surprise to Alison, who explains that her husband’s work ethic was developed while attending a Quaker school in Philadelphia from second grade through high school. “Friends schools emphasize the whole person and service to others,” she says. “Students learn how to apply themselves and get things done, which was very typical of Don.”

Returning as director

In 1976, Kerr left the Laboratory to pursue an opportunity in Las Vegas as the deputy manager of the Nevada Operations Office, which helped coordinate work at the Nevada Test Site. He then moved to Washington, D.C., to serve as the deputy assistant secretary for Defense Programs and acting assistant secretary for Energy Technology in the newly formed Department of Energy (DOE).

“The first secretary of energy was Jim Schlesinger,” Alison remembers. “He very much became Don’s mentor.”

When Schlesinger signed off on Kerr to be the fourth director of Los Alamos in 1979, Kerr—then just 40—returned to lead the Lab, succeeding Harold Agnew. A 1979 issue of The Atom magazine noted that Kerr differed from his predecessors in two key ways: he had not worked on the first atomic bombs, and he had experience in the federal government. When asked whether that background would benefit his directorship, Kerr replied, “The bureaucracy is a given, which must be accepted. Having been responsible for some of the bureaucracy myself, I can perhaps swim in those waters with some success.”

Alison recalls that “Don was really interested in the director job. It was his first job where he was in charge of something big.”

This time, the family lived in a historic Arts and Crafts house on Bathtub Row—so named because during the Manhattan Project, the homes on this street were the only ones with bathtubs. “It was a great house for entertaining,” says Alison, recalling a memorable potluck where their dogs stole steak tartare off a low table.

Among the many guests Don hosted were important visitors to the Lab, including actor and World War II veteran Charlton Heston. Heston came to narrate two classified films—The Flavius Factor, an overview of the Lab, and Trust, but Verify, about U.S.–Soviet scientific collaboration.

In a fitting full-circle moment, those short films were later declassified at the request of the Lab’s National Security Research Center (NSRC)—an organization that traces its roots to Kerr’s directorship. During that time, a Manhattan Project–era file cabinet was discovered in the Lab’s T Division. “Next thing I know, I’m going through these drawers of stuff,” recalls Alison, who holds a degree in library science with a focus on archives. Working with historian Lillian Hoddeson, Alison proposed an official archives program. With Kerr’s approval, they transformed part of a warehouse on DP Road into the Lab’s first archives—the precursor to today’s NSRC.

John Hopkins, who served as the head of weapons testing during this time, considers the creation of the archives among Kerr’s most enduring accomplishments. “There are tens of thousands of documents in there, and they were organized in a fantastic fashion that made them usable,” he says. “The archives are really a shining light for the Laboratory.”

John Browne, who would in 1997 become the sixth Los Alamos director, rose through the ranks—from group leader to division leader to associate Lab director—during Kerr’s tenure and became familiar with Kerr’s leadership style. “Don was a very focused and decisive director,” Browne says. “He was good at asking the opinion of his leadership team on major decisions, but it was clear that he was in charge and would make the decisions—it was not a consensus.”

Browne recalls that as director, “Don made many changes at the Lab, some of which were roundly criticized by the staff and others warmly adopted.” Chief among the initially unpopular reforms was the introduction of matrix management, which gave program managers responsibility for interacting directly with customers in the Departments of Energy and Defense. “Prior to this change, technical divisions—line management—carried all the power in executing programs,” Browne explains. “The decision was not popular, but Don felt we needed a better, unified interface with Washington. Matrix management, of course, still exists at the Lab today.”

In 1980, Kerr told The Atom that “the reorganizations at the Laboratory are really a matter of catching up to the changing nature of our research and development programs. These have evolved in number from 1 in 1943 to anywhere from 50 to 200 today, depending on how you aggregate programs.”

Among Kerr’s more popular initiatives were the creation of the Laboratory Fellows program and the launch of Institutional Research and Development (ISRD), which funded long-term basic and applied research to build new capabilities. Funding for ISRD came from a 7 percent tax on all Lab programs. According to Browne, after some debate in DOE and Congress, the same concept—renamed Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD)—was established at all DOE labs and continues to this day. “I consider this a major legacy of Don,” Browne says.

In 2007, U.S. Senator Jeff Bingaman agreed, testifying before Congress that LDRD “was and continues to be a mechanism at the Laboratory that has allowed for some of the very best of the research that is done at not only Los Alamos but all of our national laboratories to occur.”

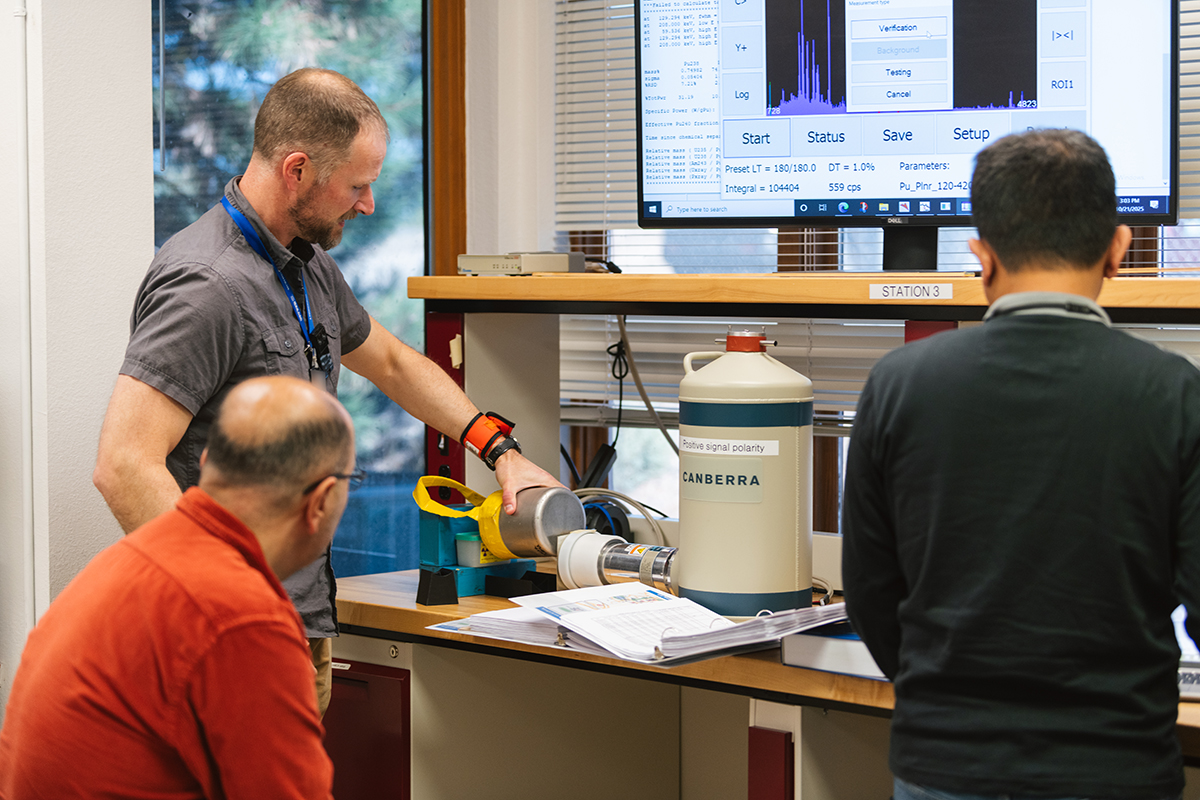

According to a 1997 Physics Today article, Kerr’s lasting contribution as director was diversifying the Lab. “Along with its traditional mission in nuclear weaponry, Los Alamos took on a multiprogram look, with activities in defense technology, microelectronics, materials research, life sciences, high-performance computing, applied mathematics, and basic and applied physics.” Many of these programs had civilian applications—including genome sequencing, which led to the Lab’s creation of a DNA database now used by the global research community.

Life after Los Alamos

By 1985, Kerr’s daughter had graduated from high school (alongside many students she’d gone to kindergarten with), and he felt the time was right to pursue new opportunities. He spent the next dozen years in private industry, first at EG&G, a Massachusetts-based engineering firm that operated the Nevada Test Site and other facilities, and later with Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) in La Jolla, California. In 1996, he joined Information Systems Laboratories in San Diego as executive vice president.

The following year, Kerr was contacted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). “He couldn’t figure out if they wanted his advice about who to hire or if they wanted to hire him,” Alison remembers.

It turned out to be the latter. In October 1997, Kerr became the assistant director in charge of the FBI Laboratory Division. FBI Director Louis Freeh said the Bureau needed “a scientific leader—someone who would bring the methodologies of science and the experience of managing scientists into that laboratory.”

Kerr later told the American Physical Society that the FBI job “was not something I’d ever expected to do, but it was such an interesting opportunity.”

In Physics Today, Kerr explained: “The scientific research and technology that I’m familiar with are exactly what’s needed by the Bureau’s lab to deal with new threats—nuclear, chemical, and biological terrorism, and computer and cyberspace crimes.”

When Freeh left the FBI in 2001, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Director George Tenet recruited Kerr to serve as deputy director for science and technology at the CIA. “The CIA and FBI are very different culturally,” Kerr told Physics Today in 2004, explaining that the FBI looks backward—to find out what happened—while intelligence looks forward, to predict what might happen. “Scientists are used to the way intelligence organizations think because a fundamental of physics is to be able to predict things theoretically.”

In 2005, then–Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence Steve Cambone—who had worked for Kerr at Los Alamos in the early ’80s—recommended Kerr to lead the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), the Department of Defense agency within the intelligence community that designs, builds, launches, and operates the nation’s reconnaissance satellites. “The secretary of defense asked me who I would suggest to be the director of the NRO,” Cambone remembers. “And I said, the guy you want is Don Kerr.” Cambone says that in addition to being technically competent, Kerr was curious and thoughtful but also direct and confident. “There was ownership on his part of his responsibilities and authorities,” Cambone says.

Kerr was sworn in that July as the 15th director of the NRO. By this time, Kerr had been out of technical work for decades but appreciated the importance of a technical perspective in intelligence work. “Physics is one part of applying all of the tools and techniques that one can think of to different parts of the intelligence problem. It’s woven in,” he told the American Physical Society in 2009. “You need a strong science and technology input, and at the same time, you need people who have field experience who know what kinds of things you can do in different places. You’ve got to build the whole team.”

Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence

In July 2007, President George W. Bush nominated Kerr to serve as principal deputy director of national intelligence, the person responsible for coordinating the activities of the nation’s 16 intelligence agencies.

“It was the only job where he was appointed and confirmed by the Senate,” Alison remembers. “As far as the process was concerned, one thing was interesting: no one ever asked if he was a Democrat or Republican.” During his confirmation hearing, Kerr was introduced by Senators Jeff Bingaman and John Warner—one Democrat, one Republican. “I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a more qualified individual than Don Kerr to entrust our nation’s intelligence to,” Warner said.

During the hearing, Kerr testified that “the intelligence community must deliver information without bias or prejudice. Intelligence analysis must be rigorous, timely, and independent from political considerations.” He warned of challenges such as nuclear proliferation, catastrophic terrorism, and pandemic disease, emphasizing that intelligence “must think ahead to ensure capabilities are available when needed.”

He was confirmed on October 4, 2007, and served until January 20, 2009.

A legacy of service and science

In retirement, Kerr remained deeply engaged in national security and science policy. He served on advisory boards for several organizations, including MIT Lincoln Laboratory and the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, and was a fellow of both the American Physical Society and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

In 2009, Kerr joined the board of trustees of the Mitre Corporation, where he was reunited with Schlesinger, the board chairman. In 2015, Kerr became vice chairman. He was chairman from 2018 to 2021.

Nancy Jo Nicholas, associate Laboratory director for Global Security at Los Alamos, recalls working with Kerr on the Defense Science Board. “Don was witty, with a dry sense of humor and a patriotic focus on using deep science, technology, and engineering to give our country a true advantage,” she says.

After moving to Denver in 2018, Kerr occasionally returned to Los Alamos. At the Lab’s 75th anniversary in 2018, he identified “gray or hybrid warfare” as the greatest emerging national security challenge. “You have to ask how nuclear deterrence fits into this new construct,” he said. “Social media has enabled things we never thought of years ago.”

In 2020, Los Alamos dedicated the Donald M. Kerr Office Building—a new secure facility named in his honor. “It’s very fitting,” Nicholas noted, “that a building where important intelligence work will be performed bears his name.”

Just three years later, Kerr suffered a stroke and never fully recovered. He died in Denver on July 13, 2025, at the age of 86. ★

LA-UR-25-31186