Transforming learning

New approaches to preserving and passing along knowledge play a key role in national security.

- Jill Gibson, Communications specialist

Nobody majors in nuclear weapons in college. Although students can study nuclear physics and engineering, the specifics of how nuclear weapons work and the complexities of their history, design, operation, and certification cannot be taught outside of a secure environment. Much of the information that Los Alamos National Laboratory employees need to know is classified and can only be shared with people who have security clearances. Once employees are granted their clearances, they have a lot to learn.

Engineer Dominic Simone started at the Lab about two years ago. “Although I had some nuclear background from my time in the U.S. Navy, I had no direct engagement or work on the design and qualification of nuclear weapons,” he says.

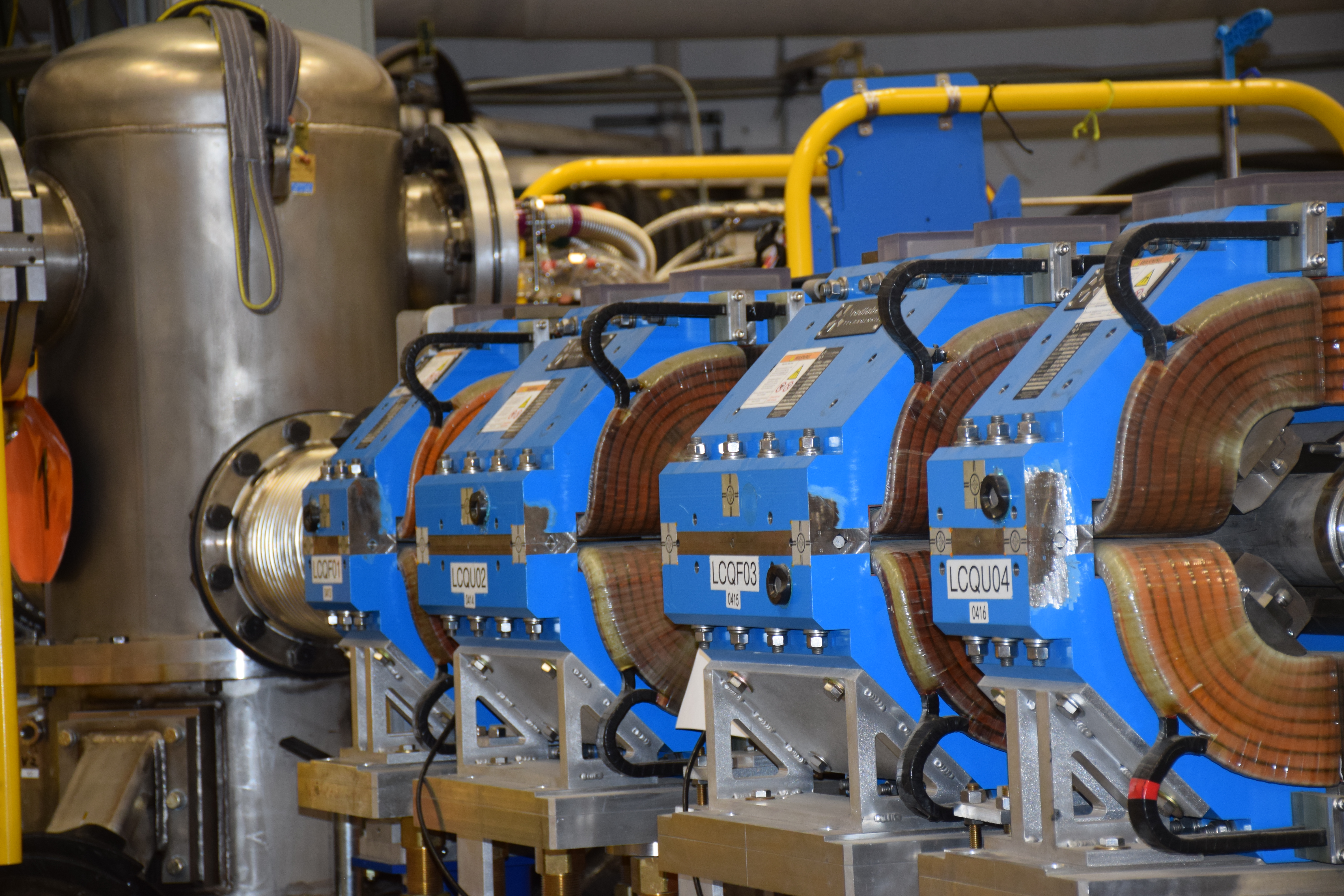

Simone is part of the team developing the nation’s first new weapon in nearly 30 years—the W93, a Los Alamos–designed warhead that will be carried on the Navy’s current Ohio-class submarines and the forthcoming Columbia-class submarines. “To understand the goals and specifications of the W93, you need dedicated time to get the information on what’s been done with past weapons designs,” Simone says. “I needed to learn about the larger national security complex and how weapons work. I needed to know how other weapons systems developers have solved problems and what experiments have been done.”

Fortunately for Simone and his colleagues, Los Alamos is revamping its approach to nuclear weapons education. Paired with a commitment to capturing and preserving knowledge and making it easier to share and retrieve information, this initiative aims to increase efficiency and decrease the amount of time it takes for new employees to get up to speed.

“When I started working at the Lab, I didn’t know what I didn’t know,” Simone says. “It’s really important to have a structure that makes learning a priority.”

A classified virtual classroom

Jocelyn Widmer, a digital learning scientist with a background in higher education, leads a Lab initiative called Weapons Learning Transformation. “Our goal is to accelerate and personalize learning,” she says. “Consider the investment the Lab makes in the staff, the need to retain employees, and the urgency of the national security mission,” says Widmer, whose title, Dean of Weapons Learning Transformation, gives a nod to the academic focus of her role. “Efficient and effective weapons learning is crucial for success.”

Widmer notes that Weapons Learning Transformation complements numerous other training programs at the Lab; however, employees working in classified weapons physics and engineering have specific education and training needs. These areas also tend to have steep learning curves. “In weapons design physics, it takes 5 to 10 years to become truly productive,” explains physicist Leslie Sherrill. “So, there’s a lot of learning that goes on here.” Additionally, new employees come to the Lab with varied backgrounds, facing different requirements on the path to proficiency.

“Onboarding and orientation are a beast,” Widmer says. “I’ve heard many employees say it takes at least three years to really know the Lab because it is so large and complex.” She points out that, over the decades, numerous weapons education programs have evolved, but, until now, there hasn’t been a systematic approach.

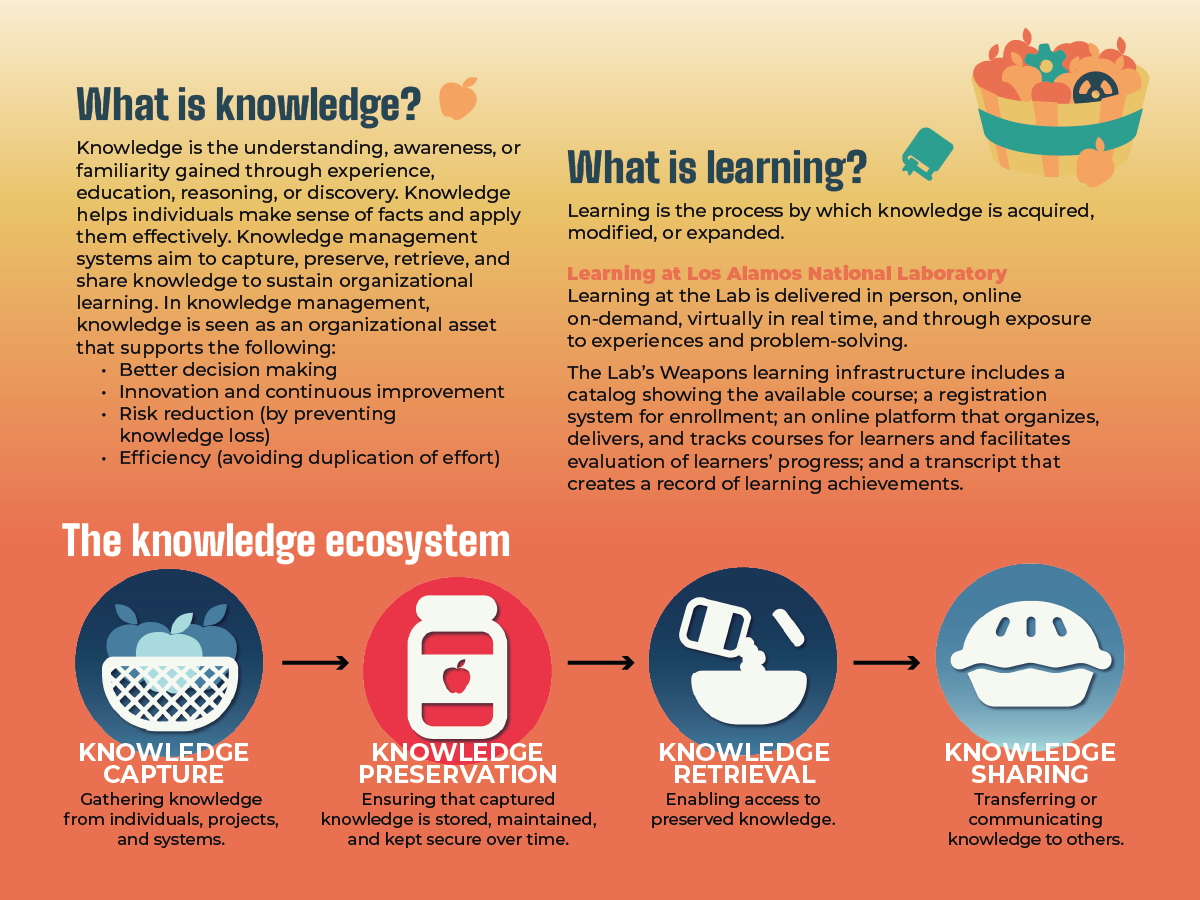

So, Widmer and her team began developing what she calls a “digital learning environment and infrastructure.” This includes a course catalog, a registration and enrollment process, an online platform for delivering and managing classified online learning, and a transcript that captures a record of each employee’s learning history and progress.

As she worked on the learning infrastructure, Widmer discovered that “the Lab had myriad weapons-related educational assets but lacked a robust way to deliver the content, particularly on the classified side.” Those assets include records, data, videos, and publications created and archived by the Lab’s National Security Research Center, which houses a vast collection of material related to the Los Alamos Weapons Program as well as historical documents dating back to the first days of the Manhattan Project. The Bradbury Science Museum and the Manhattan Project National Historical Park have also created material that can boost employee knowledge. “We have access to an amazing treasure trove of assets that have been produced in a very high-quality way,” Widmer says. “We’re able to use and package this content to achieve different objectives when creating learning pathways. Our aim is to provide access to these assets in a systematic learner-focused way.”

Until recently, almost all weapons education at Los Alamos took place face-to-face, according to Widmer. “Our early career employees who have recently completed graduate school are accustomed to learning online and having access to digital resources to augment their learning. We were bringing these brilliant young minds into the Lab and expecting them to learn in ways they had never learned before.” Widmer says now her team is developing several pilot programs that incorporate best practices for online instructional delivery to meet this new generation’s learning preferences and needs.

One of those pilots involves the Theoretical Institute for Thermonuclear and Nuclear Studies (TITANS). Often referred to as a graduate program in nuclear weapons, TITANS is a three-year course in which 10 to 15 students from the Lab’s Theoretical Design and Computational Physics divisions spend up to 20 hours a week advancing their knowledge and familiarity with the science and tools necessary for maintaining the nation’s nuclear weapons. John Scott, the Lab’s Theoretical Design division leader and TITANS instructor, recently piloted a TITANS course that incorporated digital tools and online learning. He and his students say they were pleased with the change.

“It was well received and allowed students to spend time on their own developing knowledge,” Scott says. “It helped me manage the class better and maintain records and content all in one place.” Scott says that thanks to this successful pilot class, online components will be added to all the TITANS classes. He also plans to add video-recorded lectures so students can access the class content asynchronously on demand.

The digital transformation also extends to class assignments. “We turned the TITANS homework sessions into a digital format with classified online submissions,” explains Widmer. She notes that managing hard copy classified material requires strict physical security, manual tracking, and controlled storage and lacks the digital safeguards that protect electronic data. “So, moving to digital submissions took away a lot of the burden of hard copy classified homework submissions and all that entails.”

Rachel Smullen, a computational physicist, is enrolled in the TITANS program. She says she is excited about the changes. “I was pleased to see modern tools being applied.” Smullen describes the effort as “a step in the right direction” and says she looks forward to the time when more digital resources are incorporated.

Another learning pilot focuses on the W93 team. The Weapons Learning Transformation staff has helped develop an online repository of learning, referred to as a Technical Development Card, that each member of the W93 organization must complete. “We curated the information for new employees in the W93 program—organized it, integrated knowledge checks and analytics, and developed a framework for online delivery of that information,” Widmer says, adding, “We estimate that we save each employee 55 hours in search and discovery of the information that has now been packaged into the Technical Development Card.”

Employees say they appreciate the support that the Technical Development Card provides them. “This has been an efficient way of doing things,” says Landon Cartwright, an engineer who recently joined the W93 team. “The information is not generic—it is tailored specifically to our organization, and it gets you up to speed. I really appreciated that development of such a complex system with a clear sense of direction regarding what is important.”

Simone has also taken advantage of this learning resource. “It was all laid out, and any time I would get stumped I knew where to go to find the information,” he says.

Cartwright points out that the amount of information that new employees must master can be overwhelming. “The learning curve is steep, but at least I have a set of things to go on.” He adds, “At Los Alamos National Laboratory, learning is part of the job.”

The W93 team is also paving the way for future learning by carefully documenting the decisions and processes behind the development of the new warhead. “In building the W93, we are, in many ways, working in uncharted territory,” Simone says. “Thanks to our current approach to documenting our processes, when we start building the next weapons system, we will save time.”

Cartwright agrees, saying, “The way we are managing this system will help future systems. We are publishing internally, planning for the future, maintaining records, and enabling efficient searches. We are doing what we can to make the next system easier.”

Widmer points out that learning at the Lab is never finished. “Our staff needs to continue enhancing their knowledge and skills, and we are creating easily accessible materials and learning options that make this possible.” From organizing experiential options like facility tours or classified museum visits to working with external online course providers such as Coursera to develop personalized upskilling classes, Widmer is finding new ways for Lab employees to learn more effectively and efficiently.

At the service of science

A large portion of the online videos, presentations, and information Widmer is incorporating in the Weapons Learning Transformation infrastructure originates from a team known as Weapons Knowledge Management, or KM. The KM team works to capture, preserve, retrieve, and share knowledge to sustain learning. KM’s work largely consists of recording and editing videos featuring longtime Lab experts discussing processes and decision-making. The team also hosts a classified video series called Unlocking the Vault designed to share technical weapons videos from the past.

Trinity Overmyer, who leads the KM team, says the goal is to help the Lab meet a critical need for knowledge transfer and retention. “Knowledge is in people,” Overmyer says. “Everyone at the Lab is a knowledge worker; their expertise is important to the mission, and our team is here to help them preserve and pass along what they know.”

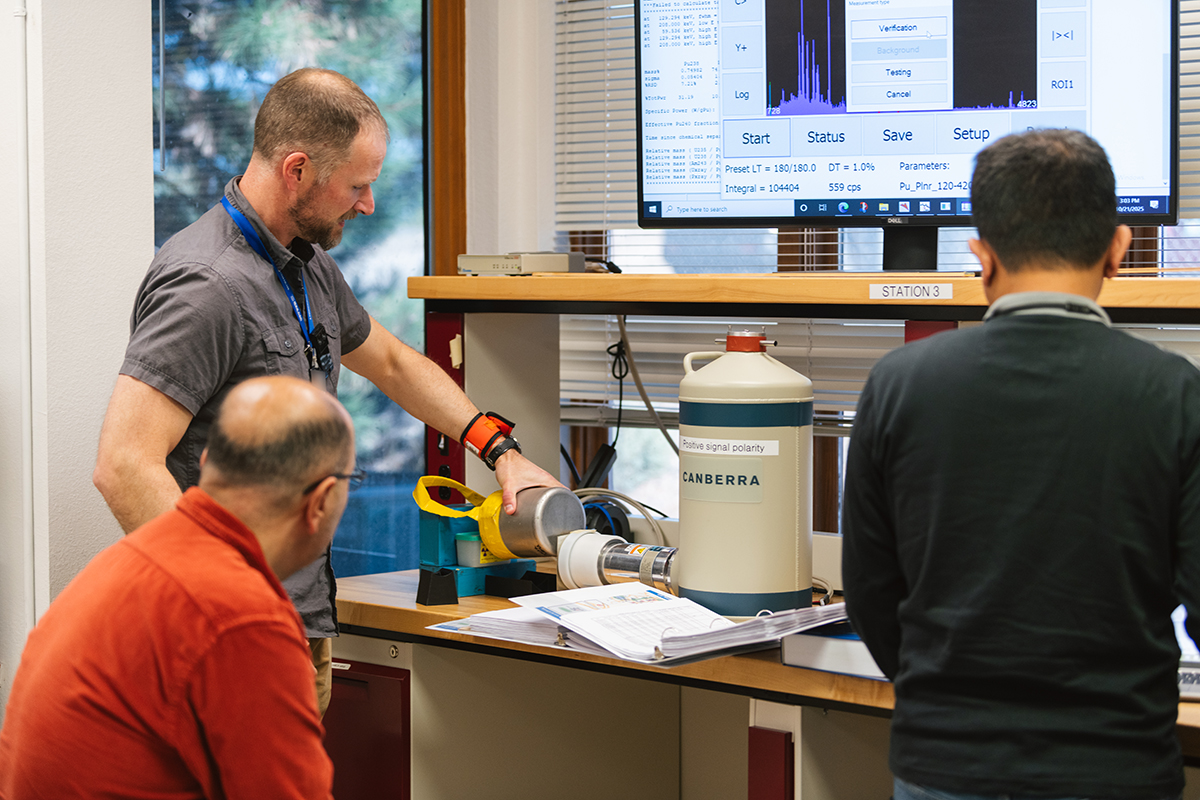

Over the past eight years since its founding, KM has made more than 100 video recordings of Lab employees sharing their technical and professional wisdom. Many of these employees are close to retirement when they decide to participate in the knowledge capture process. Lab leaders encourage staff to take the initiative to ensure their expertise is preserved for when they leave Los Alamos.

“We rely on things learned by our predecessors, and that’s why knowledge management is important,” Laboratory Director Thom Mason says. “There’s a lot captured in the brains of the people who did the work.”

Overmyer notes that her team’s work is heading off knowledge loss and avoiding duplication of efforts. “Effective knowledge management leads to better decision-making, increased innovation, and continuous improvement,” she says.

Ron Cosimi, a retired Los Alamos physicist and former nuclear test director, urges current employees to take the time to record their knowledge. He says that during the years he spent working on full-scale nuclear detonation tests, scientists were extremely busy and not focused on preserving knowledge. When the United States declared a moratorium on full-scale testing, a certain amount of information was lost. “In the past, we didn’t manage knowledge. It went from one brain to another, and now a lot of it is gone,” says Cosimi. “It’s very important for scientists to document what they are doing, how they are doing it, and why they are doing it,” he notes. “And then you put everything in one place so if someone wants to look up something, they know where it is.”

To facilitate that ease of retrieval, Overmyer and Widmer are working together to ensure the videos and other assets that KM captures get integrated into the new digital learning infrastructure. “Anything the Knowledge Management team can do to give people more time to do their work rather than searching for resources helps employees get things done faster,” Overmyer says. “Being able to support people to make learning easier supports the mission of the Lab.”

On the front lines of knowledge

Another component of the KM work involves delivering classes on the Lab’s Weapons programs, nuclear weapons, and the national security enterprise. This program, called Nuclear Fundamentals Orientation (NFO), started in 2019, and 4,000 Los Alamos employees have gone through the course since it began. While NFO is not a requirement for most Lab employees, many supervisors encourage their staff to attend it. NFO consists of two online sessions that take place synchronously through video conferencing and a three-half-day in-person classified component. Additional online sessions and in-person tours supplement this training.

Alan Scarlett leads the program. A retired U.S. Air Force nuclear weapons specialist with more than 20 years of weapons instruction experience, Scarlett says he has a passion for nuclear weapons education. “It’s important to pass on this information. We must understand the history of our nuclear weapons program—our past capabilities, the present, and our plans. We must understand the purpose of the national security enterprise. We must create a shared understanding of the weapons program and an appreciation of the mission.”

Whether online or in person, Scarlett teaches with great energy and a sense of urgency, conveying that the stakes are high. “The next Lab leaders and weapons designers could be in this class,” he says. “They need this knowledge. Do you know what happens to knowledge that isn’t shared? It disappears. It goes away.”

The audience comes from across the Lab, although most are in the Weapons program. Anyone in the nuclear security enterprise may attend the course. Scarlett says it offers key information for those interested in the fundamental mission, the national security enterprise at large, and how the labs, plants, and sites within the enterprise coordinate efforts. “We have many new employees across the enterprise who need this background,” he notes.

Scarlett concludes the final session of NFO by discussing every weapon design that has been introduced into the nation’s nuclear stockpile, pointing out several lesser-known weapons that were developed many years ago. “Do any of you know that the United States once had a nuclear drone?” he asks the audience. Several people shake their heads, sparking a flurry of questions. The participants’ interest and engagement are evident. The audience is hungry for the information that Scarlett provides.

Scarlett says the course offers more than just history. “Past concepts can spark new ideas,” he explains. “Right now, we need innovation in every conceivable manner to manage the changing geopolitical landscape.”

He stresses that knowledge plays a crucial role in national security, and he sees his role as an important part of preserving and passing along that knowledge. “When I teach, I think about my son,” says Scarlett. “I do not want my son to ever have to fight a war that I could help prevent today.” ★