Thinking inside the box

A National Security Science writer tries her hand at glovebox training.

- Jill Gibson, Communications specialist

The adage goes that you can’t understand someone’s life until you’ve walked a mile in their shoes. Recently, I set out to see whether I could understand someone’s job by training an hour in their gloves. That’s right—I wanted (literal) hands-on experience as a glovebox worker at Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Gloveboxes are sealed, steel compartments inside which radioactive materials can be safely handled. Long, heavy gloves are attached and secured to openings in the glovebox. Technicians insert their hands into the gloves to carry out a wide variety of processes inside the enclosures. One of the most important processes that requires gloveboxes is the making of plutonium pits—the cores of nuclear weapons.

A pit is a hollow sphere of plutonium that, when uniformly compressed by explosives inside a warhead or bomb, causes a nuclear explosion. Los Alamos produced the first plutonium pits in 1945 during the Manhattan Project and is now making new pits by refining and recasting plutonium from old weapons. Currently, the Lab is the only place in the United States where technicians build pits, which means supervisors can’t rely on hiring people with pit-making experience. New hires must learn one-of-a-kind skills for a one-of-a-kind job that takes place in a one-of-a-kind building. It’s a steep learning curve.

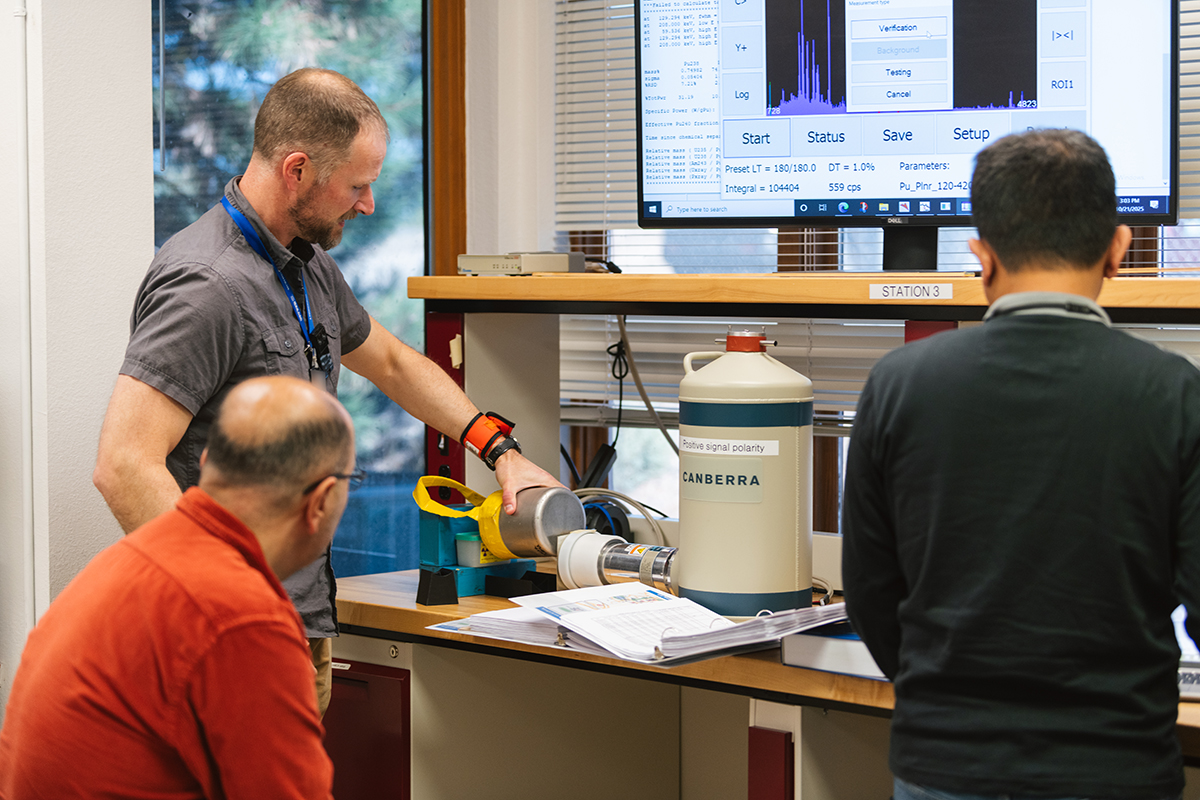

Inside gloveboxes, employees purify plutonium, cast it, machine it, measure it, test it, and more, often moving parts between different boxes using an electronic trolley system (that works like a small, horizontal elevator). But, before technicians can master specific processes, they must learn numerous safety protocols and pass written and hands-on evaluations. This training takes place through the Lab’s New Employee Training (NET) Academy for Nuclear Facility Workers, so that’s where I head to begin my exploration of how glovebox operators develop knowledge and skills for their unique jobs.

A paradigm shift in training

Kristan Cisneros, who leads NET Academy, says that since its start in 2020, the Academy has trained nearly 1,000 people in glovebox operations and fissile materials handling, which certifies them to work with nuclear materials capable of sustaining a fission chain reaction. “We bring in cohorts of 20–30 people roughly monthly,” she explains, noting that people can begin the training while obtaining the security clearances that enable them to work in the buildings where pit manufacturing takes place. Cisneros says this has increased efficiency and cut down on past training bottlenecks, which is helping the Lab achieve its pit production goals. “This is the only facility like this in the nation. You cannot bring in anybody that has the skill set that we need. So NET Academy is vital in providing those hires that foundation of knowledge for safety, for security, and for the work that they're going to be able to do.”

At NET Academy, the new hires have lectures, assigned reading, and testing before the practical training begins. Along the way, they undergo various evaluations. Although that could sound a bit intimidating, Cisneros says the employees have lots of support. “NET Academy provides the new hires with guidance and mentors. We build relationships and trust, and they know that if they have questions or problems even after their training, they can always reach back out, which boosts retention.”

Amanda Quintana supervises the technical trainers who instruct the new hires. “It’s a high-stress job for the trainers because they’re the ones who say, ‘yes, we believe this individual is capable and has the knowledge to move forward,” she says. Quintana points out that all the trainers have extensive experience working with nuclear materials, usually within the Lab’s Plutonium Facility, known as PF-4, at Los Alamos. She says the trainers are committed to each new employee’s success. “We're here to help them. We're here to make that connection. We're here to get that piece where the lightbulb turns on over their head and they understand why, or what, or how.”

Quintana explains that training begins by going over procedures, safety, compliance regulations, and more. Although I’m eager to get a true “new hire experience,” I decide to skip the paperwork, lectures, and tests (which is not something real technicians can choose to do). The next part of the training involves touring PF-4, the facility where the plutonium pits are built.

A rare glimpse inside

Visits to PF-4 are limited because of a combination of strong security measures and the facility simply being too busy to accommodate guests. I’m able to join an informational tour that is not geared toward training glovebox operators, but I hope it will provide some insights into the work and the plutonium facility.

To enter the building, we pass through numerous security checkpoints, including a state-of-the-art metal detector portal. Armed guards ensure no one gets in without thorough screening—a complicated process that doesn’t just apply to visitors. More than 1,000 employees pass through these checkpoints each day.

As a visitor, I am instructed to not wear any metal (including jewelry, an underwire bra, or outfits with a lot of snaps or zippers). Over my clothes, I wear a lab coat and shoe covers, but most employees wear yellow coveralls, adding hard hats and other personal protection equipment (sometimes including respirators), depending on the requirements of their jobs.

Most staff members work 10-hour shifts, and once inside the windowless 233,000-square-foot building, many will stay there all day. There are breakrooms and a cafeteria in a nearby building, plus picnic tables and even food trucks just outside for employees to use during breaks.

With staggered entry times and the recent addition of night and weekend shifts, PF-4 is always busy. When production teams aren’t doing hands-on tasks (and sometimes even when they are working), construction crews swarm in to chip away at a plethora of facility modernization and expansion projects.

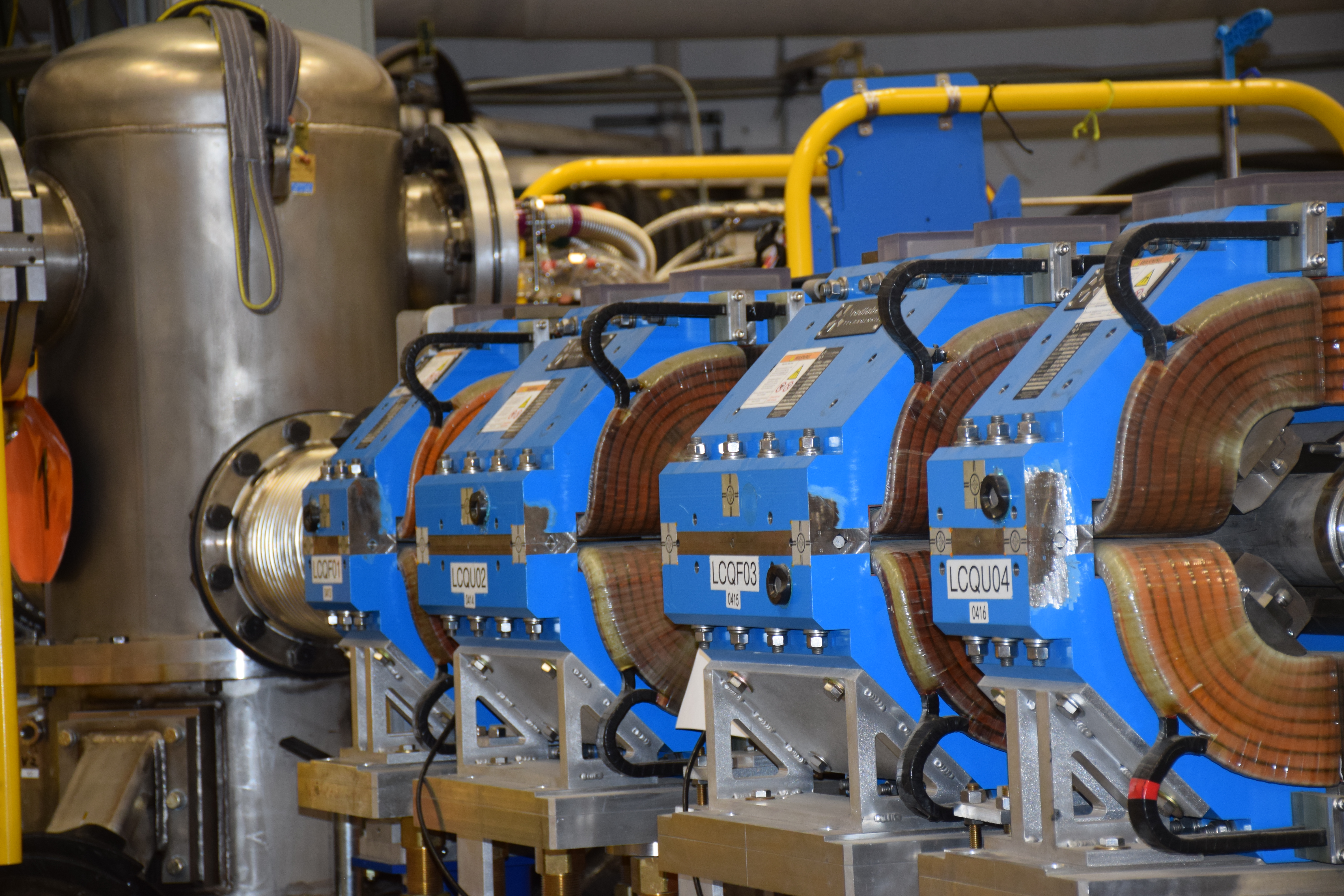

Our group visits several labs where the various processes related to pit-building take place. The rooms are filled with rows of gloveboxes, those overhead elevator-like trolleys, and a complex series of tubes, vents, cables, and other equipment.

Unlike my workplace, the rooms have no chairs or desks. Glovebox work must be performed while standing. Anti-fatigue mats soften the strain of concrete floors, and step blocks allow technicians of all heights to reach the glove ports and see inside the contained areas where they perform their work.

Signs, monitors, radiation detectors, and a highly structured sequence of procedures are in place to maintain worker safety. Employees must master important rules and processes related to working inside this nuclear facility—and that’s in addition to learning to conduct procedures with their hands inside a glovebox and developing the specific technical skills related to their roles.

After two hours in the facility, I have learned a lot, but the main thing I’ve learned is …there’s a lot to learn. My goal had been to try my hand at an introduction to glovebox training. Now, I’m wondering, “Could I do this?” The next week, I head back to NET Academy to find out.

A chance to try my hand

Daniel Garcia will be my trainer. He has been at the Lab for 31 years and has spent 19 of those working in gloveboxes in PF-4 and 6 years as a technical trainer. We will be training in what is called a cold lab—there are no “hot” radioactive materials here. The room where I will learn to work inside a glovebox is a mock facility.

With Garcia’s help, I suit up in the yellow coveralls, shoe covers, safety glasses, and the rubber gloves that I will wear the entire time I am “working,” including when inserting my hands into the gloves of the glovebox. He helps me secure the edge of my gloves to my coveralls with masking tape to create a secure seal. “This is your anti-C—anti contamination—gear,” he explains. But, before we can enter the lab, Garcia instructs me on the entry procedures, which include checking signage on the door, reviewing documents, and looking through the window into the lab to ensure there are no problems or issues inside. I’m starting to get impatient, but Garcia insists we do everything by the book.

Finally, inside the cold lab, I see rows of gloveboxes similar to the ones in PF-4. Garcia instructs me on how to check the gloves, the front of the glovebox, glass windows, and the port and ring holding the gloves. We swipe across every surface with a cloth, repeatedly surveying for radiological contamination (of course, there isn’t any in this mock facility) and examining the gloves for any discoloration, tears, or defects. “There are many controls in place that are meant to keep you safe,” Garcia says.

After what feels like forever—and is actually about 20 minutes—it’s time for me to insert my gloved hands into the lead-lined gloves attached to the glovebox.

“Put your hand in, and push it inside the box across your body,” Garcia says. I struggle with the long, heavy glove, finally managing to get my hand and fingers inside and push my arm into the glovebox. The glove is cumbersome, longer than my fingers, and difficult to bend.

“Now the other hand,” says Garcia. He instructs me on ergonometric approaches to moving my fingers. “Use a power grip with your hand in a neutral position, not pincers,” he urges me, demonstrating by slipping his hands into the glovebox beside mine and picking up a roll of tape that’s inside the box. My first inclination is to pinch my index finger and thumb together, but Gracia explains that using my fingers as pincers could cause muscle strain. Following his guidance, I try to hold my hand level (the neutral position) and grasp objects using all my fingers curled like a letter “c” (a power grip). After a few tries, I can lift the tape and hand it back and forth to Garcia, but my fine-motor-control is limited. “We use different gloves depending on the task and the amount of radiation shielding needed,” explains Garcia. “The ones you are using right now are the thickest.”

I angle my body against the glovebox, straining to look inside the glass window. “It’s hard to see in different positions so you have to learn how to work in your area,” Garcia says. “You must have an intense mental concentration on the task that you're performing while also considering everything else—the glovebox, the zone of ventilation, your position, the documents you're required to refer to and maintain.” When I say I feel fortunate to get individual instruction, Garcia replies, “We have a ratio of three students to one instructor to maintain the attention of the individuals participating and to get more interaction between the instructor and the students. But when it comes time for evaluation, it is one-on-one.”

There are also procedures for removing my hands from the glovebox, checking for radiological contamination, and tying the gloves together, inside out, outside the box to indicate they are not being used. Ending a glovebox session takes almost as long as beginning one. As a writer, I reflect that it rarely takes more than a minute for me to begin and end a project—turn on the computer and open a Microsoft Word document, save, and turn off the computer when done. I am unaccustomed to the level of detail Garcia expects from me. “You can’t be sloppy or haphazard,” he says. “You must conduct your work in certain ways to keep you and your coworkers safe and keep the equipment and the facility in operation.”

Garcia laughs when I tell him my hands are tired after just a few minutes in the glovebox. He points out that proper training and hand positioning helps with that, adding that dedicated ergonometric experts at the Lab provide guidance to help workers avoid fatigue and prevent injury. Although I don’t have time for a consultation with a glovebox ergonomist, later that day, I watch one of the ergonometric program’s glovebox worker stretching videos. Many of the stretches focus on the hands, and others involve the full body. Working in a glovebox can be a physically demanding job.

I’m accustomed to using my hands for typing, but I find that wearing the heavy gloves taxes a different set of muscles. “Do your hands get tired when using the glovebox?” I ask Garcia, who responds that as he has aged, he has lost some stamina and strength in his hands.

I ask Garcia how people respond to the three-hour glovebox training sessions. He says the new hires say they really enjoy the practical training and welcome the hands-on work. He adds that after the initial qualification and certification, glovebox operators move on to work with mentors who train them on specific processes. Once they begin work in PF-4, they must requalify and recertify every two years.

I am anxious to rip off my anti-contamination gear, but instead, I try to follow Garcia’s methodical instructions. I thank him for the training and for his thorough and patient instruction. “The approach to training is very deliberate so we can make it clear that safety is always first and foremost in people's minds, but also that there's a lot of support,” says Garcia. “Also, I want our new employees to have pride in their jobs, to understand that the work they do has an impact on our whole nation.”

I leave the cold lab with great respect for the glovebox operators, their trainers, and the work that goes on at PF-4. I have trained an hour in their gloves (okay, it was more like 15 minutes, but who’s counting), and now I have a much better understanding of the knowledge and skills required to be a glovebox operator and the important role these Los Alamos National Laboratory employees play in national security. Now, I must go home to rest my hands. ★