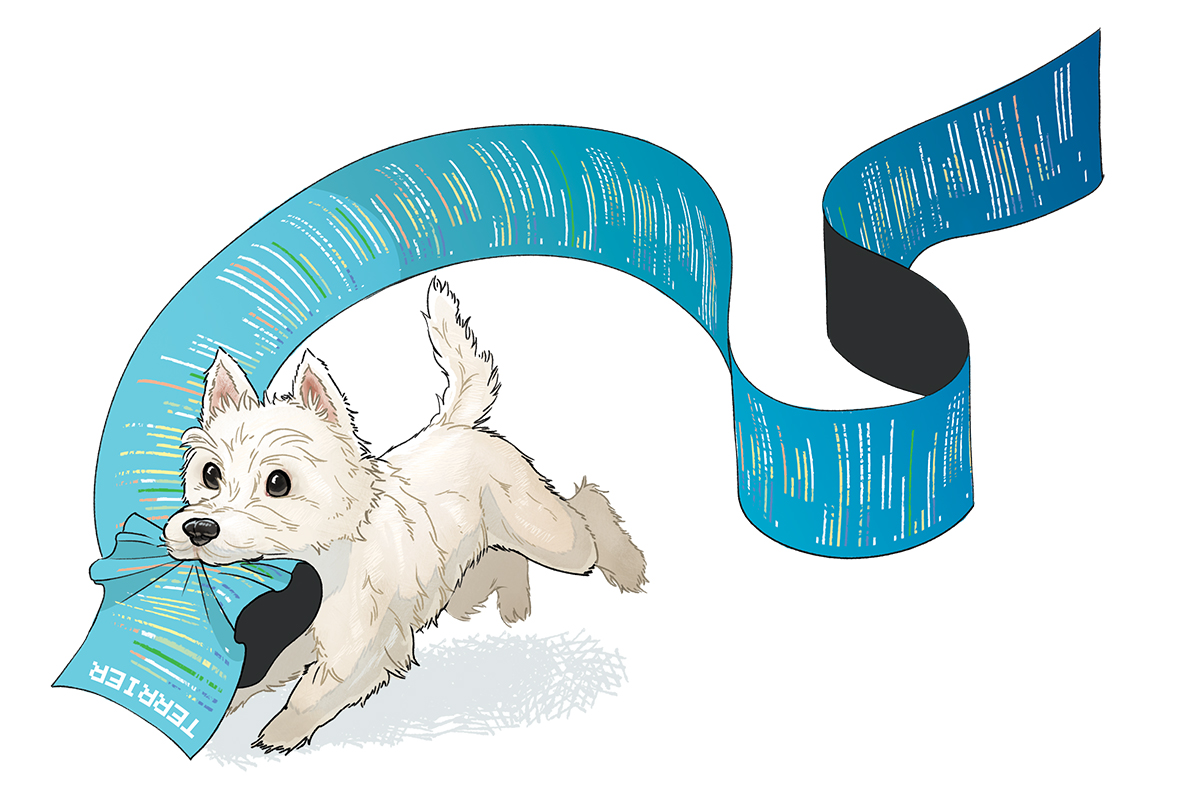

The nose knows

The Lab’s dog detectors sniff for success.

- Jill Gibson, Communications specialist

Inspecting vehicles, shipments, and facilities for explosives is all part of a day’s work for Zora, a nine-year-old Belgian Malinois on Los Alamos National Laboratory’s dog detection team. When not conducting inspections, Zora and her handler, Chris Bailey, stay busy with training. Working together, they sharpen and build on the dog’s extensive explosives detection skills.

“Currently we have five canine explosive detection teams—five dogs plus their handlers—at Los Alamos,” explains Jason Lujan, from the Lab’s Security Operations division. “We must ensure that site protection measures effectively address all potential threats and risks. The dogs are deployed to detect explosives and other prohibited materials.”

Lujan says the dogs are extremely accurate and reliable at identifying a variety of explosive materials. In fact, no technological device can match the dogs’ 98 percent success rate.

Los Alamos National Laboratory subcontractor Merrill’s Detector Dog Services—a company that also serves the Pantex Plant in Amarillo, Texas, and other government sites—supplies the Lab with dogs and handlers. Merrill’s begins training the dogs when they are seven- or eight-week-old puppies, marking the beginning of a lifetime of learning for these canine employees. Currently, the dogs working at Los Alamos include Labrador retrievers, German shepherds, Belgian Malinois, and German shorthair pointers. Bailey says personality and drive are more important predictors of training success than choosing a specific breed.

“We start by teaching the puppies to search for food, and then we imprint them on 20 to 30 different odors, training them to recognize the smells.” Bailey says. “After they can identify a variety of explosives, we begin hiding the sources and teaching the dogs to hunt for them and perform a response behavior called an alert.”

Every dog gets paired with a handler. “We’re partners,” Bailey says. “The dogs live with us, and, when we go home at the end of the workday, they just get to be dogs.” Bailey notes that handlers and dogs develop a connection. “There’s such a strong bond between me and Zora. We’re a team.”

Both the dogs and the handlers must pass annual certification exams administered by independent third-party master trainers proficient in canine certification. “We want to push the dogs to get them to the next level,” Bailey says. He explains that handlers vary the lessons, hiding things high and low and in different containers, but, despite the difficulty, “You can’t beat that nose.”

Katherine Heselton, the owner of Merrill’s Detector Dog Services, has worked with canine detection for more than 30 years and says dogs still have the power to amaze her. “We are always training—changing environments, weather, time of day,” she says. “We try to come up with ways to trick them, but they can find things anywhere, even beneath ice or concrete or underwater. It’s great to see how smart the dogs really are.”

Lujan points out that when not working, the dogs are social and friendly. “They are part of the Los Alamos security family and the Lab’s security culture. We encourage employees to chat with the handlers and get to know the dogs.”

Bailey agrees, adding that when Zora isn’t working, she can be found reclining on a comfortable spot on the couch or even sharing his pillow when they travel out of town for detection work at large venues like sporting events. “She’s my buddy. I can’t imagine life without her,” he says.

Heselton says that working with the dogs is all encompassing and rewarding. “They love their handlers, they love people, they love learning, and they love what they do.” ★