The mentor in the cockpit

Lieutenant Colonel Mike Marchand, a B-52 pilot and Air Force fellow at Los Alamos National Laboratory, has trained air crews for the nuclear mission and more.

- Jake Bartman, Communications specialist

Not long after finishing his initial training as a B-52 pilot, Mike “Cash” Marchand found himself in the middle of one of the U.S. military’s largest training exercises. Called Global Thunder, the annual exercise involves more than 100,000 personnel who simulate a response to a realistic attack on the United States, ensuring that the military’s strategic forces—including bomber crews, submarine fleets, and missileers—are ready to field the nation’s nuclear weapons at a moment’s notice.

As part of the exercise, Air Force bomber crews are tasked with boarding their aircraft and taking off as quickly as possible. Marchand recalls the exhilaration and chaos of the exercise. “A klaxon goes off, and that means to get to the airplane and start the engines,” Marchand says. “You and your crew all pile into your van, and you drive like maniacs to get out there as fast as possible. And then, when you get to the jet, everyone has a specific job to do. The pilot starts the engines, and then the navigator and the weapons-system operator start up the navigation systems as soon as there’s power.”

With the crew in place, the aircraft can taxi and take to the air, condensing a process that typically takes up to an hour to just five or six minutes. Taking off is no easy feat, however. Ordinarily, bombers wait two minutes or more to allow air turbulence to clear before following a jet down the runway. During Global Thunder, jets take off one after another, which means that the air is both rough and sufficiently exhaust-filled enough to reduce visibility. Pilots are also responsible for remembering their place in the queue and counting the jets that take off ahead of them, ensuring that they take off at the right time. “You’re sitting there thinking, OK, am I number 12 or number 13? And then you can’t even see where the other planes are going,” Marchand says.

Such conditions are challenging for any pilot, let alone one who has just finished training. During the exercise, Marchand’s B-52 suffered an engine fire during takeoff, necessitating a premature end to his plane’s participation in Global Thunder. But despite the stress involved, Marchand remembers the experience fondly. He notes that in addition to ensuring that forces are prepared to respond to an attack, Global Thunder and other exercises demonstrate readiness to the United States’ adversaries, helping to deter real-life attacks in the first place.

“The exercises are a critical piece of our deterrence strategy,” Marchand says. “What we’re really doing with exercises like that is demonstrating to the world that a preemptive strike is not going to stop the United States from responding.”

Over the course of his Air Force career, Marchand, who is now a lieutenant colonel, has participated in Global Thunder several times—both as a pilot and in other roles, including inside the Cheyenne Mountain Air Force Station (now Space Force Station) as strike advisor for U.S. Northern Command. In a career that has involved everything from flying aircraft to leading an operations support squadron and briefing high-level officials, Marchand has trained and supported the next generation of pilots, support crew, and strategists to safeguard the nation’s security.

Every year, Los Alamos National Laboratory brings one or two members of the Air Force to the Laboratory as Air Force fellows. At Los Alamos this year, Marchand is gaining familiarity with the nuclear enterprise, the better to help facilitate the transfer of knowledge between the national laboratories and the military—and within the Air Force itself.

“My goal is to learn what the Air Force needs to do to provide a more credible and more effective deterrent,” Marchand says. “I have an opportunity to learn about that at Los Alamos.”

A pilot’s progress

Marchand joined the Air Force’s Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program while he was an undergraduate student at the University of Notre Dame. He studied engineering and enjoyed the kind of thinking that engineering involves, but reasoning that he could always quit being a pilot and become an engineer but not the other way around, he applied to the Air Force’s pilot school and was selected.

After completing a joint pilot-training program with the Navy in Pensacola, Florida, Marchand relocated to Vance Air Force Base in Oklahoma, where for three years, he was an instructor pilot. In the Air Force, pilots who progress immediately from earning their wings to becoming instructor pilots are referred to as FAIPs (which stands for first assignment instructor pilot). Not all pilots are thrilled to be FAIPs, preferring operational assignments. But Marchand soon found that he enjoyed serving as an instructor.

“When you go to pilot training, you’re excited about flying, and you’re excited to get to do real things,” Marchand says. “What you don’t want to do is stay in a training role and teach students. Well, I got FAIPed, and I loved it. I loved teaching students how to fly.”

Having been selected to become a B-52 pilot, Marchand then moved to Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana, where he came to appreciate the tight-knit B-52 community and the aircraft’s versatility. “The missions you have in the B-52 reflect pretty much everything that the Air Force can do,” Marchand says. “So, you get to do some really neat stuff.”

The B-52 is unique among the Air Force’s three heavy bombers in the breadth of nuclear and conventional munitions it can carry. Since the 1990s, the B-1 hasn’t carried nuclear weapons, and the stealth B-2 is designed to carry its payload—whether conventional or nuclear—internally, passing undetected through often-adversarial airspace to deliver precision strikes.

By contrast, the B-52, which has been part of the Air Force’s fleet since the mid-1950s, was designed to fly intercontinental missions, delivering enormous payloads to targets on the other side of the world (the aircraft can travel some 8,800 miles without refueling). With its massive bomb bays and plentiful underwing “hard points” for munitions, the B-52 can carry up to 70,000 pounds of ordnance.

When the B-52 was designed in the 1950s, the bomber was intended to field nuclear gravity bombs, among other weapons. Due to shifting strategic needs, the B-52 ceased carrying nuclear bombs around five years ago (the B-2 continues to deliver B61 nuclear bomb variants). The B-52 still carries air-launched cruise missiles armed with nuclear warheads, however.

The B-52’s flexibility is part of the reason why it has remained in service, with various upgrades, for seven decades. The aircraft isn’t about to retire, either, with additional upgrades to the jet expected to keep it in service until the 2050s or longer.

Training for the nuclear mission

To Marchand’s surprise, upon completing his B-52 training, he was selected to become an instructor for new B-52 pilots (due in part to his experience as an instructor at Vance). Marchand’s time as a B-52 pilot instructor proved relatively short-lived, however. Just a year and a half later, he was selected to teach B-52 air crews about the nuclear part of their mission, helping to train warfighters to field a key component of the United States’ strategic deterrent.

B-52 air crews that train for the nuclear mission study command and control procedures carefully, ensuring that they’re able to authenticate the codes they receive that direct them to execute a nuclear strike or to “retarget”—that is, to change course—after a strike order has been given. Because of the tremendous responsibility that comes with carrying out nuclear missions, crews must be trained to the highest standards of professionalism. Training in areas such as tactics, delivery profiles, and safety checks is comprehensive and rigorous: There’s no margin for error.

Although some of the knowledge necessary to conduct a nuclear mission can be acquired in classrooms, it is by putting such knowledge into practice during exercises such as Global Thunder that crews demonstrate their mastery. Global Thunder has been conducted annually since 2014, but the Air Force has a much longer history of conducting full-scale training exercises to ensure its readiness to field the nation’s strategic deterrent.

Marchand traces these exercises to famed Air Force General Curtis LeMay. In the aftermath of World War II, LeMay was tasked with building up the Strategic Air Command (SAC), which, as a part of the Air Force, had responsibility for controlling and fielding the United States’ strategic bombers and, later, intercontinental ballistic missiles. To ensure the readiness of SAC’s bomber fleet, LeMay was reputed to arrive unannounced at Air Force bases and order their strategic bombers to take to the air as quickly as possible. If the fleet’s response time was too slow, LeMay would relieve wing commanders of their duty.

The goal of such exercises, Marchand says, was to ensure that if the United States were under attack, its bombers would be able to take to the air quickly enough to survive and deliver a counterattack. “The way that General LeMay approached the Cold War was with the mindset of, ‘we’re at war,’” Marchand says. “That mindset filtered through SAC.” Indeed, air crews took such exercises so seriously that they’d hurry to their aircraft even if they were in the shower when a drill was announced (crews were reputed to keep extra flight suits on board their aircraft in case a “klaxon drill” necessitated running to one’s jet clad only in a towel).

In 1992, at the end of the Cold War, SAC was dissolved, although the organization was reactivated and renamed Air Force Global Strike Command in 2009. Today, it is through coordinated exercises such as Global Thunder—rather than impromptu visits by high-ranking generals like LeMay—that Global Strike Command ensures the readiness of the United States’ strategic bomber fleet.

The view from underground

Marchand found leading training for the nuclear mission at Barksdale to be remarkably fulfilling. “The nuclear mission is just about the biggest impact you can have,” Marchand says. “It’s got to be done, and it’s got to be done well, or else you don’t have an effective deterrent. If you don’t have a credible response to a nuclear attack, it doesn’t matter how good you are at conventional warfare.”

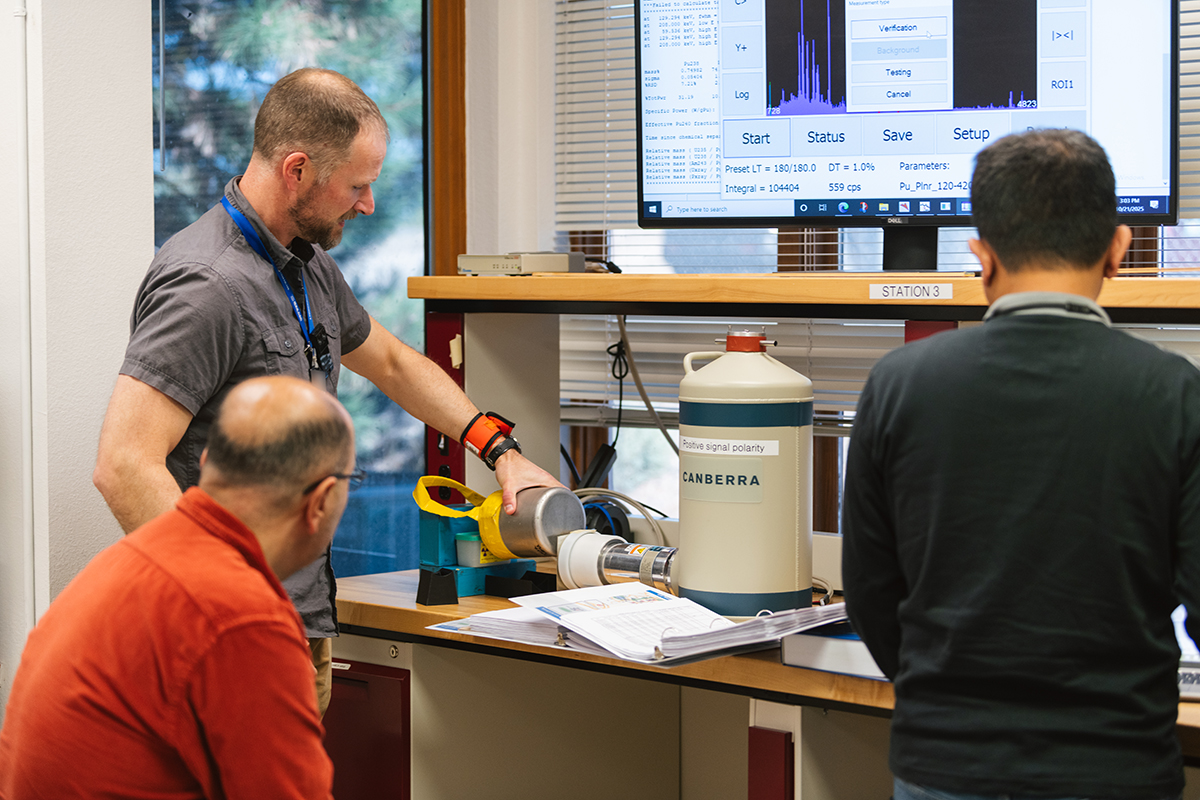

In 2015, then-Los Alamos Director Charlie McMillan visited Barksdale. Having been introduced to McMillan, Marchand asked the Laboratory director to speak with a cohort of students who were training for the nuclear mission. McMillan agreed, explaining to Marchand’s students the role of national laboratories such as Los Alamos in providing a nuclear deterrent for the Air Force to field. In particular, McMillan discussed stockpile stewardship—the process by which the nation’s national laboratories certify the safety, security, and reliability of the nuclear deterrent without full-scale testing.

The talk piqued Marchand’s interest in Los Alamos, and when he learned about the Laboratory’s Air Force Fellow program, he was even more intrigued. “From then on, I wanted to come to Los Alamos,” Marchand says.

It would be another decade before Marchand would come to the Laboratory, however. In the meantime, he’d see the nuclear enterprise from another perspective when he accepted a role at the Cheyenne Mountain Air Force Station (as the facility was then known) in Colorado.

Cheyenne Mountain, which is near Colorado Springs, was built in the 1960s to withstand a nuclear attack: The facility was constructed inside a mountain beneath some 2,000 feet of rock. Today, the facility serves as the alternate command center for North American Aerospace Defense Command (better known as NORAD) and U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM). NORAD is a joint United States–Canadian organization that monitors North American airspace—providing early warning of missile attacks, for example—and USNORTHCOM oversees a range of missions related to homeland and national security.

Marchand spent four years working at Cheyenne Mountain. In his capacity as a strike advisor, Marchand was responsible for advising USNORTHCOM’s commander on strategic options in the event of a conflict. He was surprised to find that NORAD and USNORTHCOM were involved in Global Thunder, too, demonstrating the way in which many parts of the United States’ military work together to maintain and field the nuclear deterrent. “When I was at Barksdale, teaching the nuclear mission, I thought, well, I know a lot about this,” he says. “And then I got to Cheyenne Mountain and realized I didn’t know a whole lot. It was an eye-opening experience.”

A supporting role

Even at Cheyenne Mountain, Marchand found himself not just completing a job, but training others to work as strike advisors, too. It was during this time, he says, that he began considering what he was most interested in doing in his career. “I was trying to decide, you know, should I leave the Air Force and go fly for airlines, work half as hard, and have a great life?” he says. “A lot of my buddies were doing that at the time.”

Ultimately, however, Marchand realized that his ambitions differed. “What I really like is having the opportunity to make an impact on someone in a positive way,” he says. “And I thought, what are the jobs that have the most of that? The three that I thought of were your squadron commander, your first instructor pilot, and then whoever took you under their wing as a mentor. And those are the kinds of jobs that I realized I wanted to do.”

Such considerations helped lead Marchand to accept a position as leader of the 80th Operations Support Squadron (OSS) at Sheppard Air Force Base in Texas. The 80th OSS is part of the 80th Operations Group, which is in turn under the 80th Flying Training Wing—a wing that conducts both basic and advanced pilot training.

If working at Cheyenne Mountain had opened Marchand’s eyes to new aspects of the nation’s strategic mission, leading the 80th OSS proved enlightening in a different way. With a staff of some 550 people, the 80th OSS carries out many key supporting functions at Sheppard, including operating and maintaining the airfield itself (ensuring that the pavement is in good condition and that the runway is well lit) as well as handling airfield operations—training and staffing the control tower with controllers, radar operators, and radio operators. Other 80th OSS employees provide and maintain life-support systems for air crews (parachutes, helmets, and survival kits) and more.

Although the 80th OSS is not itself responsible for training pilots, the squadron plays a critical role in enabling the 80th Flying Training Wing to fulfill its mission. “As a pilot, it was really eye opening to see just how much behind-the-scenes work went into getting me in the air,” Marchand says. “It was a fantastic opportunity to get close to that. And it was also fantastic to get to know other communities in the Air Force. I learned a lot there, not just about leadership, but also about various other careers in the Air Force.”

Marchand spent two years leading the 80th OSS before being promoted to deputy commander of the 80th Operations Group (of which the 80th OSS is a part), where he served for a year before coming to Los Alamos.

Destination: New Mexico

Nearly a decade had elapsed since, as a nuclear-mission instructor at Barksdale, Marchand met Los Alamos Director Charlie McMillan and learned about the possibility of spending a year at the Laboratory as an Air Force fellow. In the intervening years, while working in command and control and then as an operations support leader, Marchand retained his interest in Los Alamos. Having applied for and been offered the fellowship, he jumped at the opportunity to relocate for a year to northern New Mexico and learn about the nuclear enterprise from a national laboratory’s perspective.

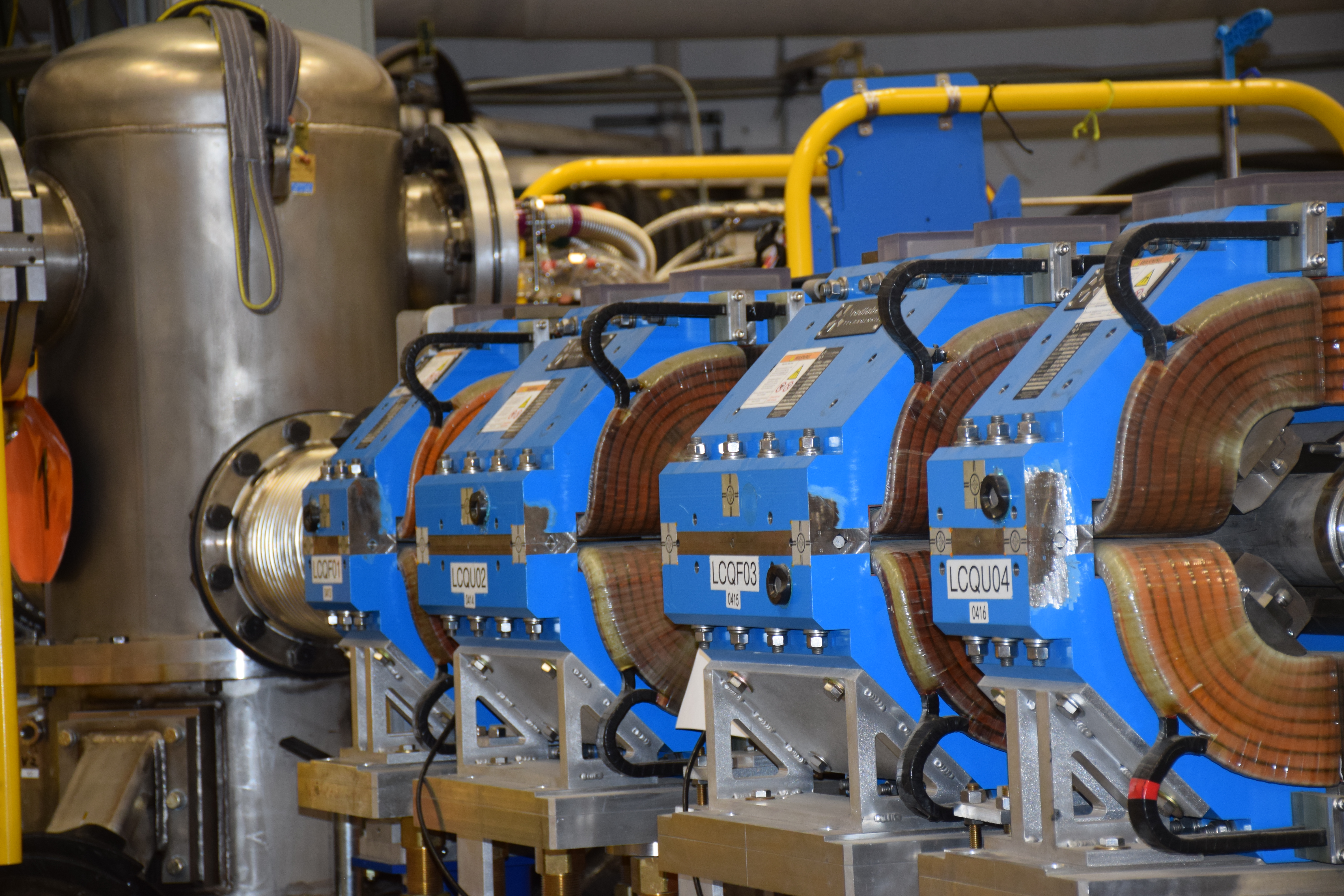

At Los Alamos, Marchand is steeping himself in the Laboratory’s broad national security portfolio, learning about everything from weapon development to chemistry research, the better to bring this knowledge to the military and to support the Air Force’s nuclear mission. (He is also enjoying a break from the 60-hour work weeks that came with serving in squadron command.)

Although Marchand isn’t certain where he’ll end up after his time in Los Alamos, he anticipates continuing to serve the Air Force’s nuclear mission in some capacity. But he expects that wherever he goes next, training and mentoring will remain central to his work.

“For me, getting to fly and support the nuclear mission have always been more like side benefits,” Marchand says. “What I really like the most is being able to make a positive impact on someone else. That’s what makes it worth getting up in the morning.” ★