Fast track to the future

At Los Alamos National Laboratory’s Dual-Axis Radiographic Hydrodynamic Test facility, students gain hands-on experience in accelerator operations and applied physics research.

- Jill Gibson, Communications specialist

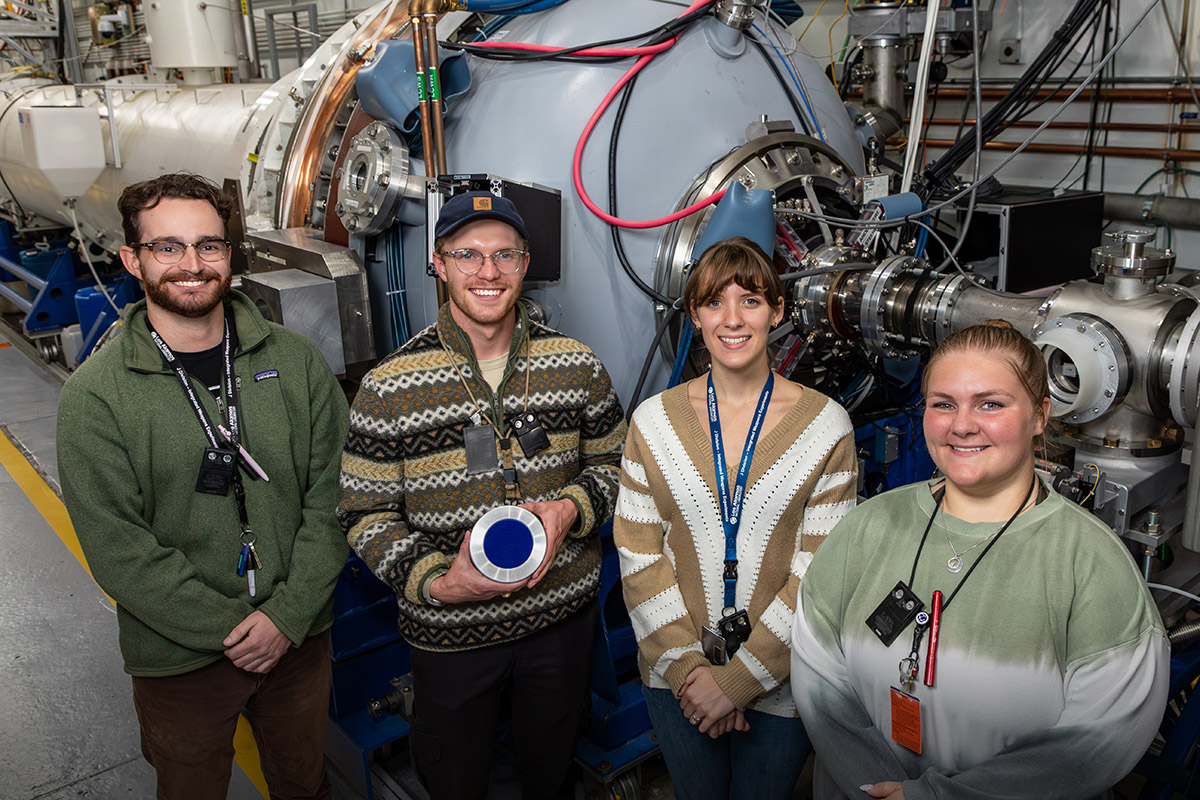

Twenty-three-year-old Jenna Sardelis was at a crossroads. She had completed a bachelor’s degree in astrophysics and was trying to decide what to do next.

“I wasn’t sure, so I was applying to graduate school and job hunting at the same time,” she remembers. “Then, I came across a job posting for a post-bachelor physics researcher at Los Alamos National Laboratory.”

A few months later, Sardelis moved from Florida to New Mexico for a unique hands-on learning experience in accelerator physics at the Lab’s Dual-Axis Radiographic Hydrodynamic Test (DARHT) facility, which uses two linear accelerators to conduct experiments to help ensure the safety, security, and effectiveness of the nation’s nuclear weapons.

“I have gained so much knowledge here,” Sardelis says. “You are never not learning. It’s an incredible opportunity.”

Sardelis owes much of her good fortune to Los Alamos physicist David Moir. About two years ago, Moir came up with the idea of starting a postbaccalaureate program for the Lab’s Engineering, Operations, and Physics group within the Integrated Weapons Experiments division. This group develops DARHT capabilities, operates the accelerator, and conducts research and development.

Moir, who started working at Los Alamos 54 years ago as a graduate student, wanted to create a pipeline of qualified young physicists. He proposed hiring students who had recently completed their bachelor’s degrees. His goal was for the recent college grads to help with research and operations while gaining skills and knowledge and preparing for graduate school. Moir had seen that graduate programs in physics were becoming increasingly competitive due to decreased funding. With fewer graduates to choose from, he was worried the Lab might struggle to find qualified scientists in future years.

“At first I was hesitant,” says Howard Bender, who leads the group. Then he considered how fast the workload at DARHT was growing. “With the demands of the experiments for the W93 [the new nuclear warhead that the Lab is designing for the U.S. Navy’s submarine-launched ballistic missiles] and other modernization efforts, we have to have the people.” So, Bender gave the proposal the green light and says he hasn’t regretted the decision. “When I met the first cohort of students, I realized, ‘Wow, this could work.’”

Moir hired three students in the first year and four in the second. “These were very strong applicants,” says Mike Jaworski, the group’s physics team leader. “Through this program, we are already hiring and preparing the sort of folks our Lab needs.” After completing a year in the program, one of the students has already left for graduate school but is staying in touch with his Los Alamos mentors. “If these students end up back at the Lab after grad school,” Jaworski says, “it’s a huge win.”

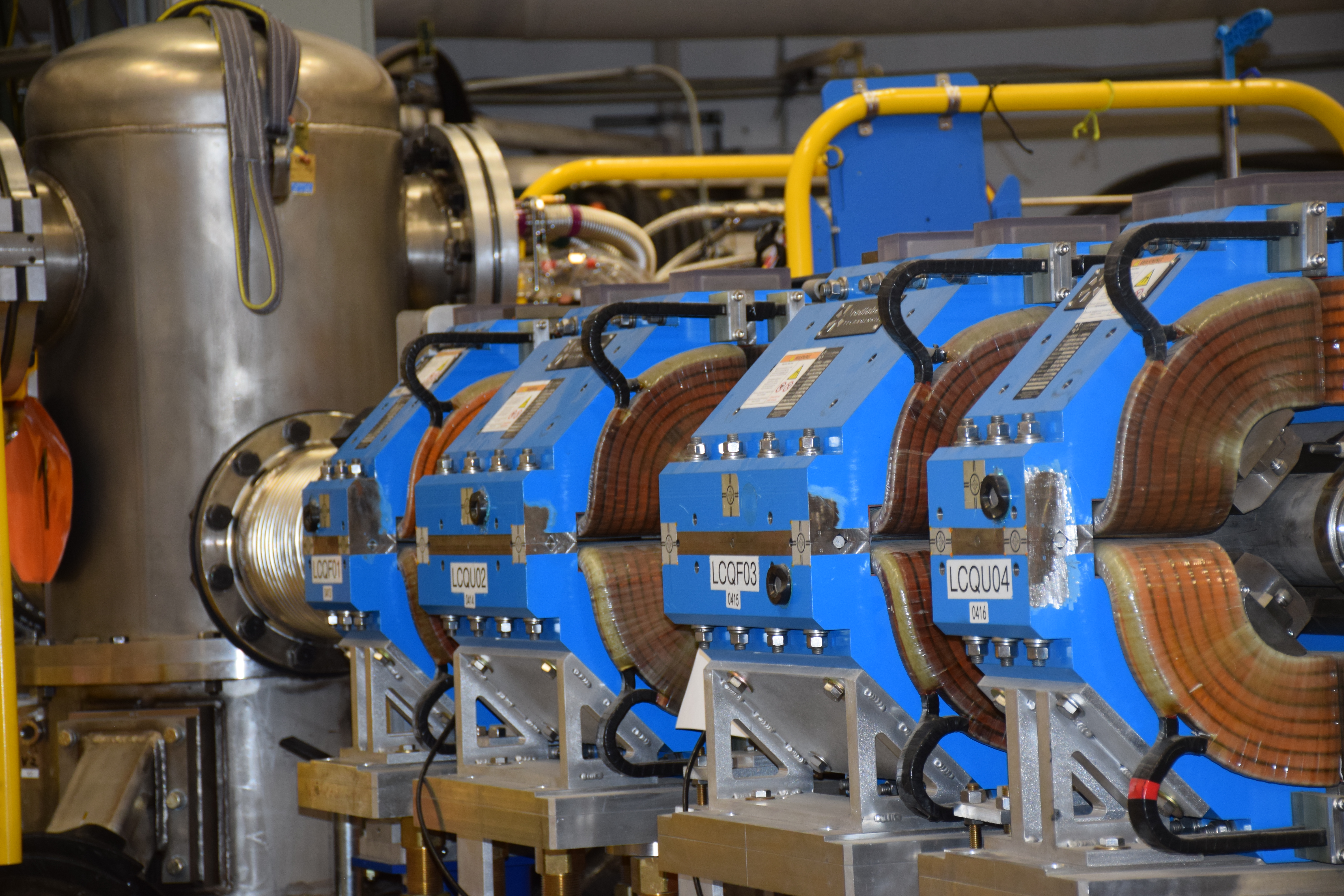

Operating accelerators

DARHT consists of two linear-induction accelerators arranged at right angles to one another. Each accelerator produces a powerful electron beam. Within the accelerator, magnets couple to the electrostatic fields and accelerate electrons to extremely high energies. The high-energy electrons hit a metal target and are deflected, converting the beam's kinetic energy into x-rays to produce freeze-frame radiographs (high-powered x-ray images) of mock nuclear weapons components detonating inside a steel containment vessel. These images, along with information produced by other tools, create data sets that scientists use to improve and verify computer models for nuclear weapons. “DARHT plays a critical role in national security,” Bender says. “That’s why it’s essential that we hire people who understand the facility. These students are filling a gap.”

Before starting the postbaccalaureate program, Thomas Magee completed an internship at Los Alamos while earning his bachelor’s degree in physics and aerospace engineering at Texas A&M University. Magee says he was excited for the opportunity to return to the Lab after graduation. “We are getting on-the-job training in a one-of-a-kind facility,” he says. “You don’t get classes like this in school.”

Students begin the program by developing a thorough understanding of the facility. They start by training alongside the accelerator operators.“We basically embed them with the operators so they can build familiarity with the tools and how DARHT’s functions impact experimental results,” Moir says.

The operators teach the students about the facility’s many systems. “We monitor everything,” explains accelerator operator Nicholas Vigil. “Magnets, vacuum, power supply, target… there’s always a problem to solve.” Operators also train the students to press the button to initiate, or fire, the experiment. This is an opportunity that few students in physics graduate programs (and even fewer in bachelor’s programs) ever get.

Jasmaine Baca, another accelerator operator, helps the students master the unique vocabulary and skillset needed to operate the accelerators. “Our work is very hands-on, and the students are fast learners,” she says.

The students learn to run the accelerators and troubleshoot issues. They analyze photon and bremsstrahlung radiation and become proficient using equipment, including digital oscilloscopes, high-speed cameras, and fiber-optic spectrometers. They discuss experiments with the accelerator operators and the physicists in the group.

Operations team leader Manolito Sanchez says that, although the students learn from the operators, the operators also learn from the students. “We have a collaborative relationship,” Sanchez says. “They teach us a lot.” Sanchez, who has worked at the Lab for 27 years, says there’s always something new to learn about the facility. “This is the most interesting place I have ever worked,” he adds, noting that the students bring in new ideas and questions, challenging the operators and sharing perspectives from their physics training with the technical staff.

“I am actually applying everything I learned in my undergraduate physics classes,” says Owen Sneddon, who began the program after completing his bachelor’s at California State University, Long Beach. “We’re getting once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to gain an understanding of the complexity of an accelerator and its subsystems. There are lots of moving parts.”

As their mentors have explained, understanding all those moving parts and how they interact and impact experiments is crucial for the students’ growth as physicists. “While we are doing experiments, it’s important for us to know how the machine is working,” says Michigan State University physics graduate Sienna Frost. “Particle accelerators are not taught in college.”

Conducting research

After spending approximately six months learning to work as accelerator operators, the students begin research.

“Our projects are based on questions that the physicists in the group want to explore,” Sardelis says. One of Sardelis’ projects is designed to help prepare the DARHT facility for the possible addition of a third electron beamline to expand capabilities. Her work involves analyzing the radiation emitted by the second beamline and predicting possible impacts on experiments.

Like every other part of the program, the research is adding to her overall knowledge of accelerator physics. “Whether we are operating the accelerators or doing experiments, we are learning every day,” she says.

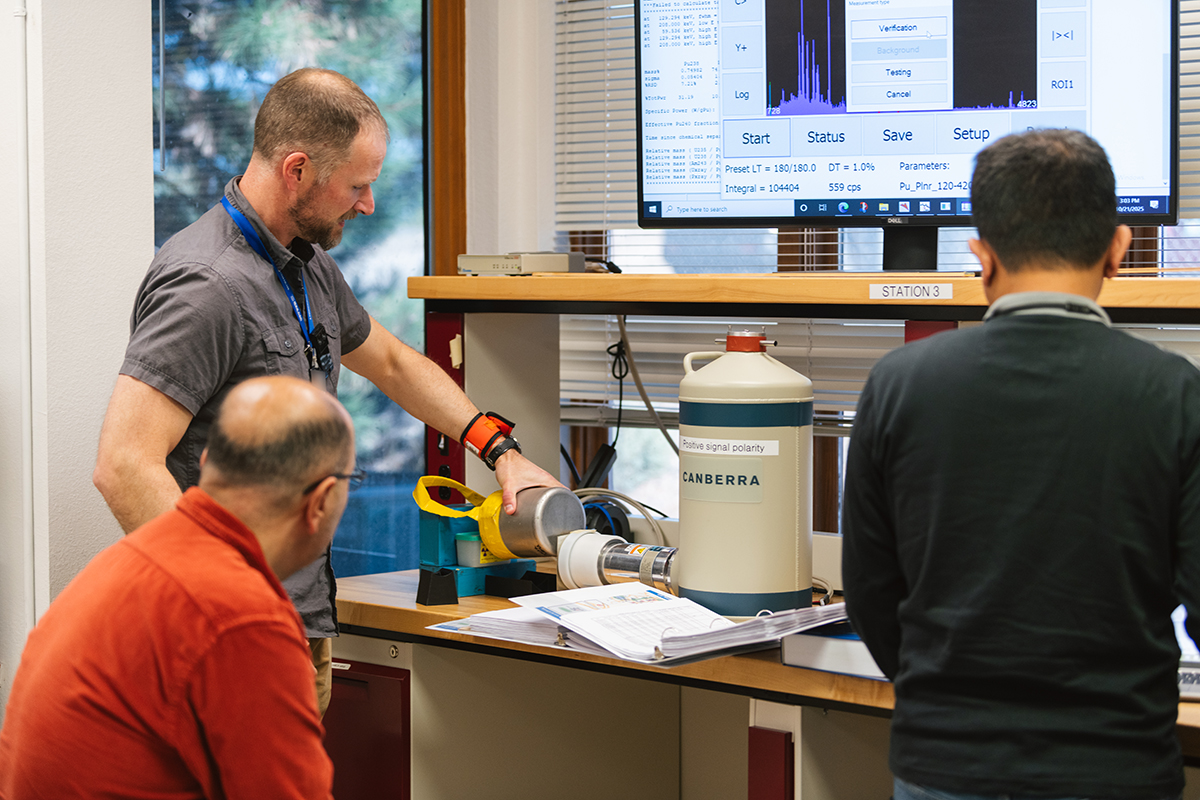

Sneddon is working on a project that involves using gamma spectroscopy to study materials that become briefly radioactive when exposed to high-energy photons. “This helps improve how we measure radiation doses during radiography at DARHT,” he explains. “My experiment has left me with questions that only further experiments can answer.”

Moir says he tries to encourage such curiosity. “There’s nothing better than being asked a question,” he says.

“We have lots of back and forth—lots of different perspectives,” Magee says. “Everybody knows something you don’t know, and you might know something someone else doesn’t.”

Magee is collaborating with Frost on research that applies computer modeling and simulation to experimental designs. “I went from feeling kind of unsure about applying for grad school to conducting graduate-level research at a national lab,” Magee says.

Jaworski points out that, as recent bachelor’s graduates, the students didn’t come to the Lab with significant research experience. “In college, they were assigned homework. Here, we are telling them, ‘we have a problem, and we don’t know how to solve it,’” he explains. “Our goal is to make them independent researchers. We are essentially research advisors. We treat them like graduate students, mentoring them, reviewing, and supporting their work.”

As part of this research, Jaworski ensures the students receive support to travel to professional conferences and other accelerator facilities to conduct and view experiments. “Part of doing research in modern times is learning that no one lab has everything. It becomes part of the skillset to travel to and work with other labs.”

The students also can attend classes through the U.S. Particle Accelerator School, a national program that offers training related to particle accelerators and associated systems. Additionally, the students have access to tours, seminars, and colloquia offered at the Lab. “Los Alamos has lots of resources for students, and we encourage them to take advantage of that,” Jaworski says.

But both the students and scientists agree that some of the best resources are the informal ones. Every other Friday at 8 a.m., the physicists and students meet on the patio of a local coffee shop. Armed with laughter and caffeine, they discuss recent success and failures. Both the mentors and the students welcome the opportunity to interact and learn.

“I love this job,” Sardelis says. “I love what I do and the people I work with.”

Meanwhile, Moir is gearing up to start reviewing applications for the next cohort of postbaccalaureate students. “Sifting through applications and interviewing the students takes some time and effort,” he says, “but, we’re growing the next generation of accelerator physicists, and that’s an investment that will pay off.” ★