The Race to Nonproliferation: The Baruch Plan

- Owen Summerscales, Editor

Two bombs marked the end of the deadliest war in history. As the dust settled from the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, the world found itself weary of warfare and weaponry, but it faced a frantic effort to avoid a nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union—uneasy allies at best during World War II. The Baruch Plan, presented to the newly formed United Nations in 1946, was the first formal proposal from the United States for international control of nuclear energy. It sought to prevent nuclear proliferation through an unprecedented framework of safeguards, verification measures, and international oversight. Although it ultimately failed to achieve support and was followed by an international arms race,1 it is still relevant today both in terms of its legacy in nuclear safeguards and as a valuable source of historical lessons.

Precursor to Baruch: The Acheson-Lilienthal Report

At the end of World War II, the United States was the sole possessor of nuclear weapons. Henry Stimson, Secretary of War under President Harry Truman, had warned Truman during the war that without an effective international system to regulate nuclear energy, a “disaster of civilization” would likely ensue as a consequence of an uncontrolled global arms race. After the war, in December 1945, the United States, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom agreed to establish the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC) to explore mechanisms for controlling nuclear weapons and energy. Through this commission, both the United States and the Soviet Union sought to establish a system of nuclear regulations to prevent another major conflict—meanwhile, the Soviet Union was secretly developing its own atomic bomb using covert information gained from Los Alamos via espionage.

In January 1946, the US government formed a special advisory committee, led by Dean Acheson and David Lilienthal (former Assistant Secretary of State and director of the Tennessee Valley Authority, respectively), to develop a plan to control the use of nuclear energy. This work resulted in the Acheson-Lilienthal Report, published in March 1946, which proposed international control over the production and use of nuclear energy to prevent nuclear weapons proliferation. The report suggested creating a global authority to manage all weapons aspects of the nuclear fuel cycle, leaving only peaceful applications under sovereign control.

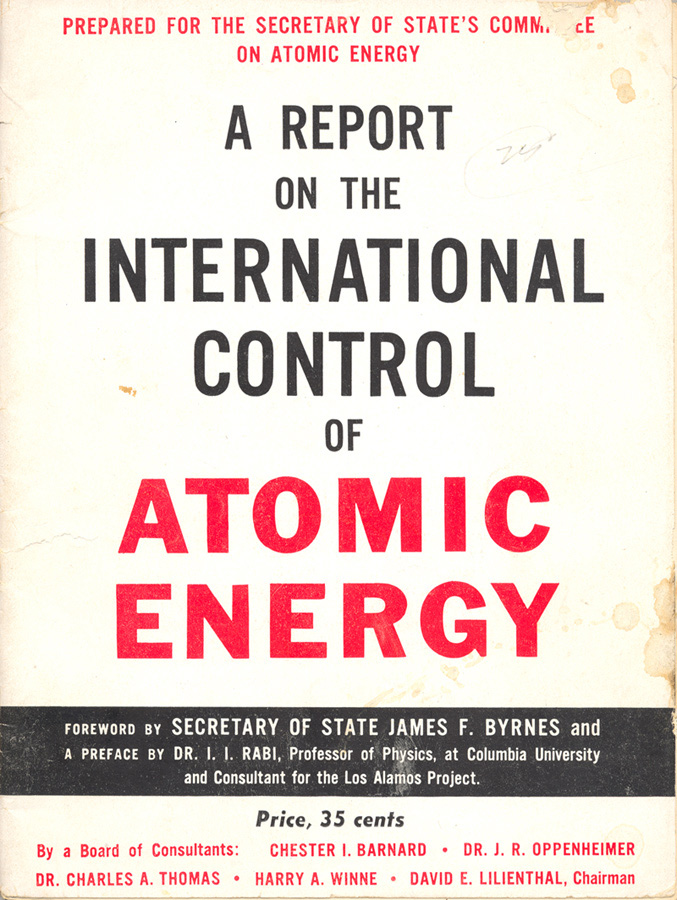

The Baruch Plan was based on The Report on the International Control of Atomic Energy— generally known as the Acheson– Lilienthal report—written by a committee chaired by Dean Acheson and David Lilienthal with Robert Oppenheimer as the lead technical advisor in early 1946.

Robert Oppenheimer was the lead technical advisor to the committee and the primary author of the final report. Oppenheimer believed that a nuclear arms race should be avoided at all costs and, furthermore, hoped that the very existence of the bomb would eliminate warfare—period—saying, “If the atomic bomb was to have meaning in the contemporary world, it would have to be in showing that not modern man, not navies, not ground forces, but war itself was obsolete.” Needless to say, this was an ambitious goal. However, the idea of outlawing weaponry had precedent—the 1925 Geneva Protocol prohibited the use of chemical and biological weapons in warfare following World War I.

The Geneva Protocol lacked enforcement mechanisms but established a legal precedent and a strong stigma against the use of these weapons. Prior to this, the 1899 Hague Convention had sought to ban the use of poisonous gas projectiles but was largely disregarded. However, after the devastating effects of chlorine gas in trench warfare, the Geneva Protocol gained significant traction, leading major powers to largely refrain from using such weapons during World War II.

Oppenheimer hoped that after witnessing the effects of the atomic bomb, the world could be persuaded to follow a similar path for nuclear weapons. But whereas the Geneva Protocol only prohibited the use of chemical weapons, not their ownership, Oppenheimer sought the outright abandonment of nuclear weapons.

As such, the Acheson-Lilienthal report proposed the creation of an international authority—the Atomic Development Authority (ADA)—to physically control and regulate all nuclear industries. The ADA would:

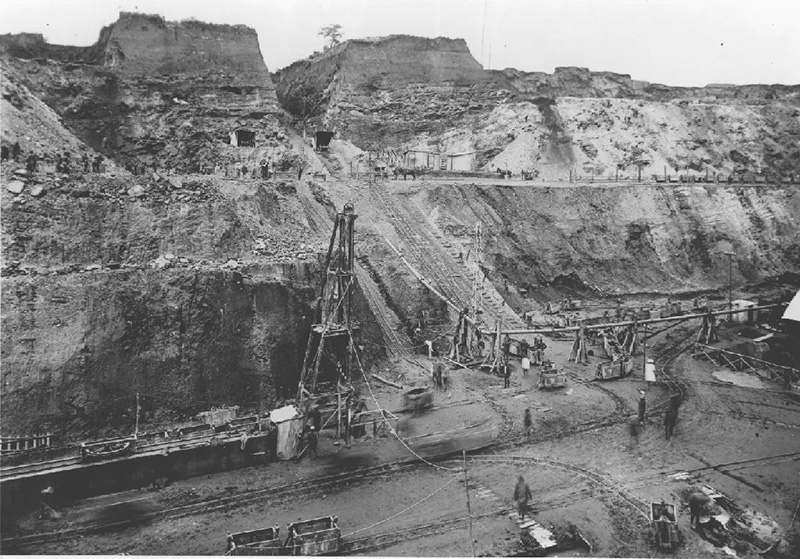

- Own and control all uranium and thorium mining worldwide

- Oversee all nuclear research and production facilities to ensure they were used for peaceful purposes

- Conduct international inspections to prevent covert nuclear weapons programs

- Provide licenses to countries wishing to pursue nuclear energy for peaceful applications

The report explicitly stated that the ADA must remain at the cutting edge of nuclear technology: “It [is] absolutely essential that any international agency seeking to safeguard the security of the world against warlike uses of atomic energy should be in the very forefront of technical competence in this field.” The report made it clear that if the ADA simply focused on enforcement, it would not be well-enough informed to recognize threats as they arose.

Next, the report suggested a path toward ultimately eliminating nuclear weapons through international cooperation. Much like the Geneva Protocol, enforcement would rely on transparency and cooperative security measures rather than immediate punitive actions, and thus, the Acheson-Lilienthal report hinged on US-Soviet cooperation.

Last minute change: The Baruch Plan

Alex Wellerstein, historian of nuclear science at the Stevens Institute of Technology, notes in his book Restricted Data that the philosophy of the Acheson-Lilienthal report “was largely rooted in Oppenheimer’s belief that international control had to be based on something other than secrecy.” This was why there was a focus on controlling uranium: “Without sources of raw uranium, no amount of knowledge could possibly make an atomic bomb,” says Wellerstein.

Commenting on this proposed bottleneck for creating weaponry, Los Alamos historian Nic Lewis says that controlling uranium wasn’t too controversial, at least in the United States— and at the time, uranium ore was thought to be a rare and therefore potentially controllable resource. However, he continues: “What became controversial was the included idea that the US would relinquish its nuclear stockpile and would share its secrets with Soviet Union, entering into a pact with the Soviets not to develop more atomic weapons. Well—Truman wasn’t really on board with that last part.”

With US-Soviet tensions rising, Truman refused any agreement that would eliminate US nuclear weapons without guarantees that the Soviet Union could not develop its own. The day before submitting the Acheson-Lilienthal report to the UN, Truman appointed Bernard Baruch, a senior statesman who had been an advisor to Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, as the US delegate to the UNAEC, trusting him to defend American interests.

Baruch modified the plan, adding the mandatory inspection of nuclear sites with the threat of sanctions against countries that weren’t adhering to the stipulations. Most importantly, he added an onerous clause that there would be no veto power in the UN Security Council over these sanctions or inspections. This was significant— the Security Council was established on the basis that the five permanent members (i.e., the main Allied Powers US, UK, USSR, China, and France) all maintained a right to veto any substantive resolution. Also—significantly—the plan stipulated that the US would only begin the process of destroying its nuclear arsenal after the plan was implemented.

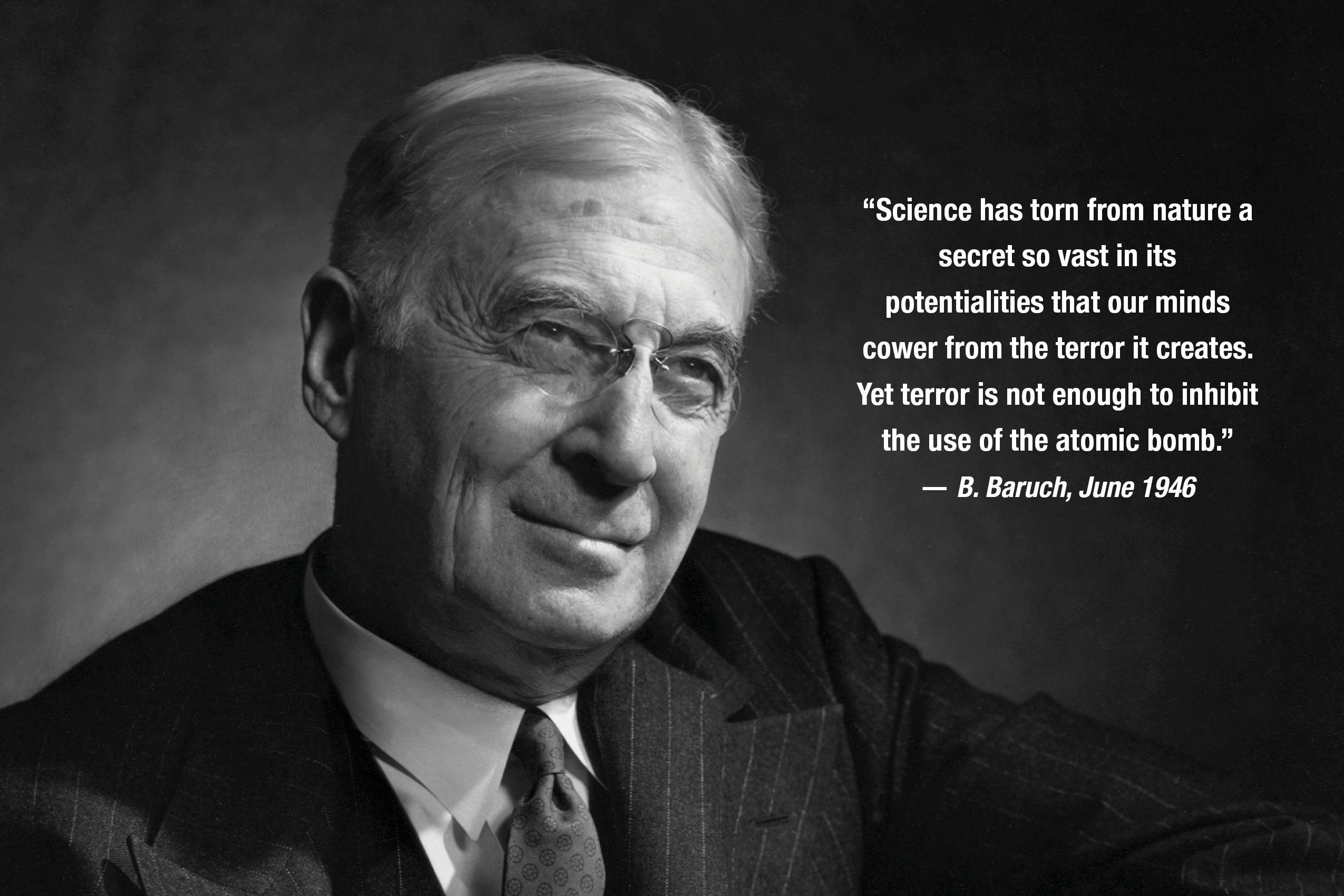

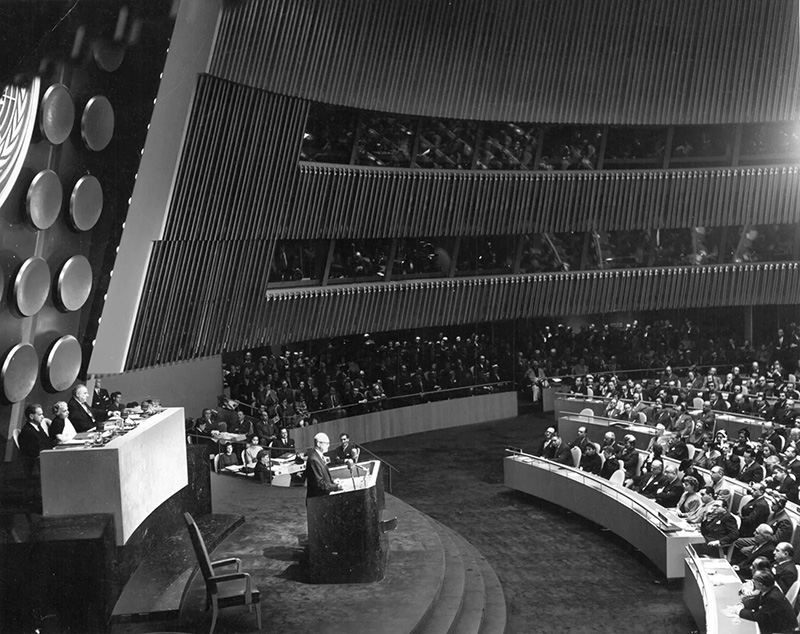

The Acheson-Lilienthal report had advocated for trust-based regulation, while the Baruch Plan emphasized sterner, enforcement-driven control and failed to provide the Soviets with security assurances. Nevertheless, in Baruch’s speech to the UN, he passionately implored the Soviets to cooperate: “Behind the black portent of the new atomic age lies a hope which, seized upon with faith, can work our salvation. If we fail, then we have damned every man to be the slave of Fear. Let us not deceive ourselves: We must elect World Peace or World Destruction.” In closing, Baruch said that the plan was “the last, best hope of earth.”

Lewis says, however, that this hope was a “long shot.” “It was pretty well accepted that the Soviets would not go along with those provisions because they were a bit touchy about Western inspectors coming into Soviet territory, along with sanctions that could not be overruled by veto—at that point, they believed the US had an unfair advantage in the Security Council.”

Although the Soviets were cautiously interested in the Acheson-Lilienthal report, they rejected the Baruch Plan immediately, seeing it as a US attempt to maintain nuclear dominance.

Whispers and handshakes

Many people have pointed to the covert nature of the Manhattan Project as sowing seeds of mistrust between the United States and the Soviet Union. This included an ambitious system of classifying fundamental scientific knowledge as secret—even keeping hidden the discovery of new elements plutonium, curium, and americium.

Lewis explains that “Henry Stimson argued that nuclear knowledge is a matter of nature, and you can’t just hide it—and that trying to hide it would just encourage the Soviets to develop their own bomb secretly. This would just create the very situation you wanted to avoid by trying to keep everything tightly wrapped.”

An unraveling of the secrecy protocols that sprang up around the Manhattan Project was planned in the Acheson-Lilienthal report, which stated: “When the plan is in full operation there will no longer be secrets about atomic energy.” The Baruch Plan largely preserved this focus on restriction of nuclear materials over information, and all subsequent nonproliferation schemes have followed this principle.

The Soviet counterproposal, the Gromyko Plan, called for a complete and immediate nuclear disarmament before establishing international control over nuclear materials—a reversal in order from the Baruch Plan. The US could not accept this as without a robust verification system, and they feared that the Soviet Union (or any other country) could continue developing nuclear weapons in secret. As such, stalemate was reached and no further attempts were made to attain disarmament through the UNAEC, which dissolved in 1949.

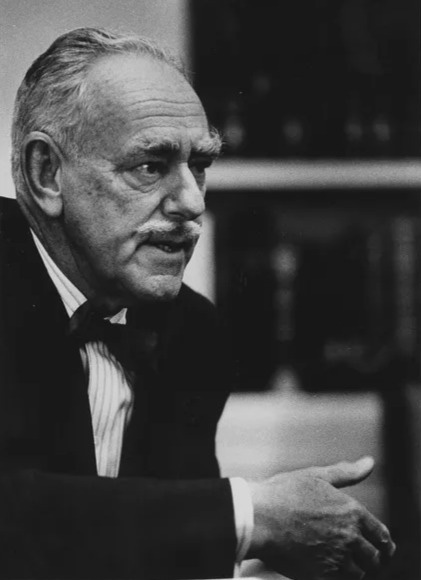

Oppenheimer’s reaction

Oppenheimer saw the failure of the Baruch Plan as predictable based on pre-existing tensions because it was “a negotiating position, not a basis for agreement.” He deeply lamented this turn of events, however, given its utmost importance: “To answer simply that we have failed because of non-cooperation on the part of the Soviet government is certainly to give a most essential part of a true answer. Yet we must ask ourselves why in a matter so overwhelmingly important to our interest we have not been successful; and we must be prepared to try to understand what lessons this has for our future conduct.”

Oppenheimer critiqued the US failure to engage the Soviet Union directly at the highest levels, instead of relying on UN forums that lacked real diplomatic power and accused US politicians of maintaining a contradictory stance, advocating for openness while simultaneously guarding nuclear secrets.

In the following years, Oppenheimer remained engaged in nonproliferation discussions, chairing the General Advisory Committee (GAC) of the Atomic Energy Commission, but became more realistic about global disarmament. In 1949, he and the GAC opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb, arguing that it was unnecessary and morally problematic, but the bomb program continued in spite of these objections. After this defeat, he moved away from advocating for disarmament and instead supported arms control and managing nuclear risks, before his security clearance was notoriously stripped from him in 1954, effectively ending his influence on US nuclear policy. At the end of his career, he became director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, where he focused on the broader ethical implications of science and technology, often speaking about the responsibilities of scientists and the moral implications of nuclear weapons.

“To answer simply that we have failed because of non-cooperation on the part of the Soviet government is certainly to give a most essential part of a true answer. Yet we must ask ourselves why in a matter so overwhelmingly important to our interest we have not been successful; and we must be prepared to try to understand what lessons this has for our future conduct.”

– Robert J. Oppenheimer, Foreign Affairs, January 1948

Atoms for Peace and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)

Reactor technology remained under tight control in the US after the war—if you could build a reactor to generate power, you could build one to produce plutonium for weapons. But this changed in 1953 when President Dwight D. Eisenhower introduced the Atoms for Peace program, a modified successor to the Baruch Plan, in which selective sharing of US nuclear know-how would be exchanged with countries in a promise to not develop nuclear weapons. Disarmament was, however, pushed to the background, remaining a distant objective at best.

“Releasing knowledge of fission for peaceful purposes would have been a big concession for the US and a major carrot for countries to join the international agreement,” says Lewis. “It was a pretty remarkable idea.”

Eisenhower proposed an international agency to regulate and distribute nuclear materials for peaceful purposes, which led to the establishment of the IAEA in 1957—a weaker version of the ADA proposed in the Baruch Plan—which still oversees nuclear safety and nonproliferation today (the program’s name lives on today in IAEA’s motto—“Atoms for Peace and Development”). While the ADA was intended to own and distribute nuclear materials, the IAEA was assigned a more limited role, focusing primarily on regulation and oversight. This was more realistic on several levels—by the 1950s, uranium ore was found to be more abundant than previously believed, making the idea of controlling uranium mines no longer workable.

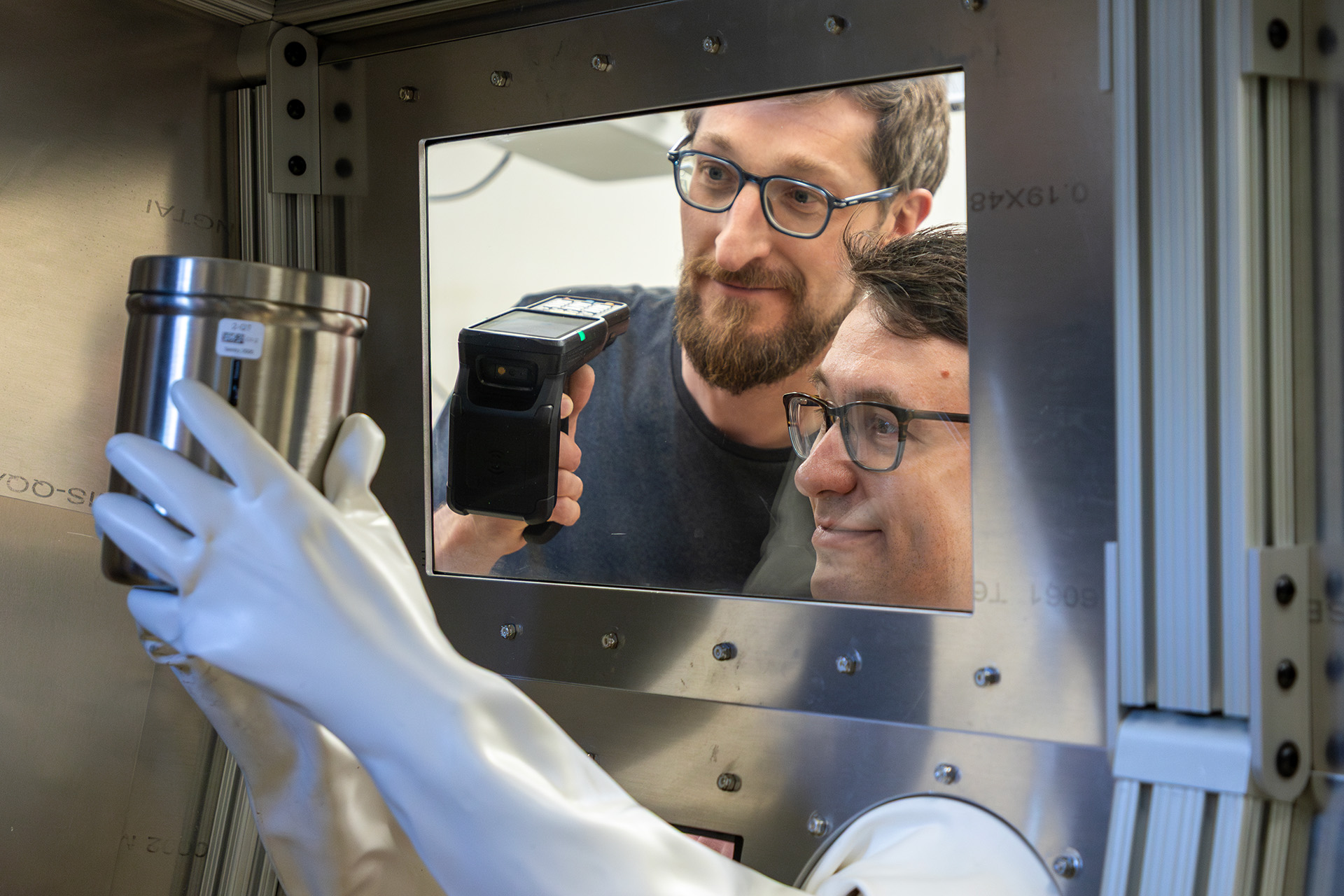

The establishment of the IAEA led to the need for technological solutions to safeguarding and verification, in particular instruments that can be used in nondestructive assays (NDAs) of nuclear material and remote measurements. In the mid-1960s, after working at the IAEA, Los Alamos physicist Bob Keepin established the Los Alamos Nuclear Safeguards Program to address this challenge, and the Laboratory has been at the forefront of these efforts ever since. Today, all IAEA inspectors must undergo training at Los Alamos National Laboratory on the use of NDA instruments, many of which were originally developed there (see p4).

Although successful in some regards, Atoms for Peace led to the rise of independent nuclear weapons programs (e.g., France, India, Pakistan) as countries that initially received peaceful nuclear assistance and later weaponized their programs—the opposite result from the scheme’s intent. These weapons programs became legitimized under the subsequent Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) treaty of 1968.

The Soviet Union officially rejected Atoms for Peace, viewing it as a US propaganda tool designed to maintain Western nuclear dominance while restricting Soviet influence. Stalin and his successors were extremely resistant to intrusive onsite inspections from Western countries, a situation that hampered safeguarding efforts, persisting for decades. However, this deadlock was broken over time as technological advancements—such as satellites, seismic monitoring, and air sampling—made it possible to monitor nuclear activities remotely.

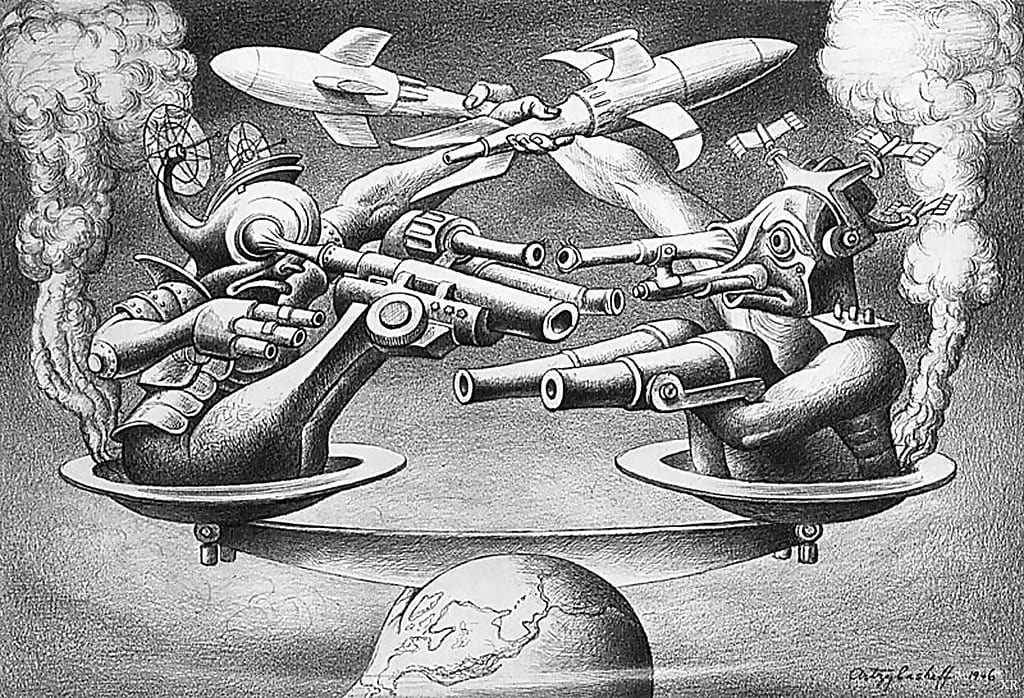

Atoms for Peace ultimately did little to temper the US-Soviet arms race, which ballooned between the early 1950s and the mid-1980s, resulting in the production of well over 50,000 nuclear weapons worldwide. Peace in some sense may have been brokered, but it rested on a fragile pact of mutual vulnerability. The Cold War ended because of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Lessons from the Baruch Plan: Safeguarding AI?

What insights can we learn from the Baruch Plan? And are they relevant today?

Many argue that these lessons are more important than ever, especially with the rise of advanced computing technologies like AI, which may require international safeguards similar to those once proposed for nuclear materials. “Are we in September 1945, for AI?” Lewis asks. “We now know these are a threat, but we don’t what the implications are. Are we going to just keep ambling towards the point of no return?”

In 2021, Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute published a paper entitled International Control of Powerful Technology: Lessons from the Baruch Plan for Nuclear Weapons. The authors conclude that nations prioritize national security over cooperation and that secrecy can be counterproductive as it increases mistrust and reduces opportunities for collaboration (related to the security dilemma in international relations), undermining the very things necessary to safeguard dangerous weapons. Lewis agrees, saying that history “affirms that you need a good faith, large-scale, international coalition to prevent runaway arms races that have the potential to impact the lives of everyone, whether that’s a thermonuclear weapon or a gen AI. Let’s apply those hard-learned lessons into the way we integrate technologies into society.”

Summary

The 1946 Baruch Plan was a bold attempt to nip nuclear weaponry in the bud when only a handful of warheads existed. Vested state interests and national sovereignty triumphed over the desire to avoid an arms race, however, and the genie refused to be put back in its bottle. Nevertheless, the Baruch Plan remains a pivotal moment in the history of nuclear governance, and its emphasis on safeguards and international oversight has significantly shaped the modern nonproliferation regime, in particular the IAEA, NPT, and other ongoing arms control initiatives. The technical challenges of nonproliferation continue to drive much of today’s nuclear research, with Los Alamos National Laboratory remaining a key player in advancing safeguards. Today, lessons from the failed plan remain relevant as nations continue to navigate the complex balance of national security and international cooperation, with powerful new technologies such as AI looming on the horizon.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Bob Hackenberg, Nic Lewis, Jake Bartman, Julie Grahame and the Estate of Yousuf Karsh, and Getty Images.

1 Bernard Baruch is credited for popularizing the term “Cold War” in a 1947 speech. However, the phrase was first coined by the writer George Orwell in his 1945 essay “You and the Atom Bomb,” published just two months after the Japanese bombings.