From Starlight to Safeguards: The SOFIA Gamma-Ray Spectrometer

- Owen Summerscales, Editor

Analyzing the composition of actinide materials is particularly challenging in environments such as Los Alamos National Laboratory’s nuclear production facility (PF-4) or at nuclear reactor sites. Radioactive processes can produce extremely complex mixtures of actinides and decay or fission products, each contributing gamma-ray signals, and despite decades of advancements in gamma spectroscopy, these signals remain notoriously difficult to deconvolute in situ using conventional techniques. To address this, researchers at Los Alamos have adapted ultra-sensitive superconductor technology originally developed for astrophysics. This innovation— SOFIA (spectrometer optimized for facility integrated applications)—comprises a series of prototype gamma spectrometers that overcome many of the limitations inherent in traditional systems, representing a major leap forward in gamma-ray nondestructive assay (NDA) capabilities.

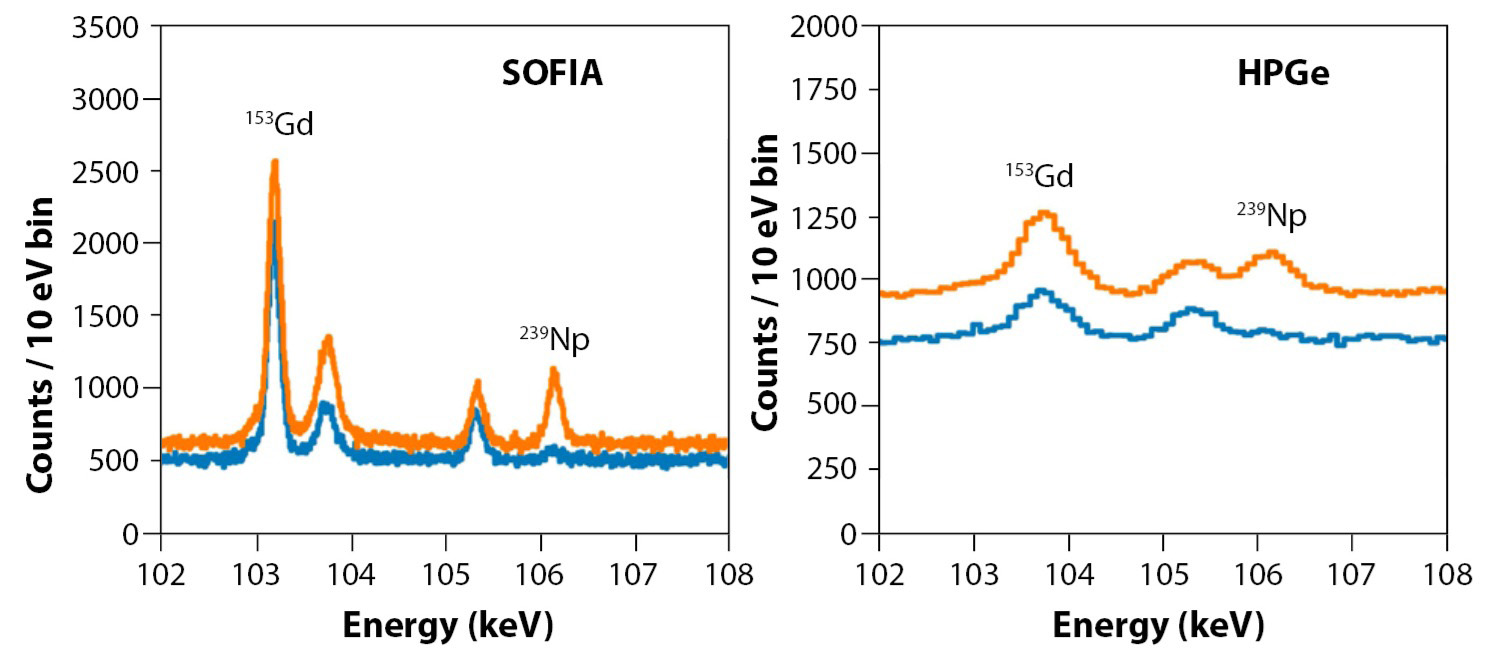

At the heart of SOFIA lies a microcalorimeter array that dramatically reduces measurement uncertainty by delivering spectral resolution an order of magnitude beyond industry-standard high-purity germanium (HPGe) detectors. This level of precision eliminates problems caused by closely spaced or overlapping energy peaks, combined with a high Compton scattering background—challenges that are particularly problematic when measuring large items such as those found in PF-4. Advances such as these could reduce the cost and time required for nuclear material accounting measurements and also offer advanced solutions for safeguarding the next generation of reactors. Furthermore, SOFIA's advances are being integrated into a new generation of NDA tools, forming part of an ongoing series of microcalorimeter spectrometers based on transition-edge sensor (TES) technology.

Ultra-high resolution: Detecting more isotopes

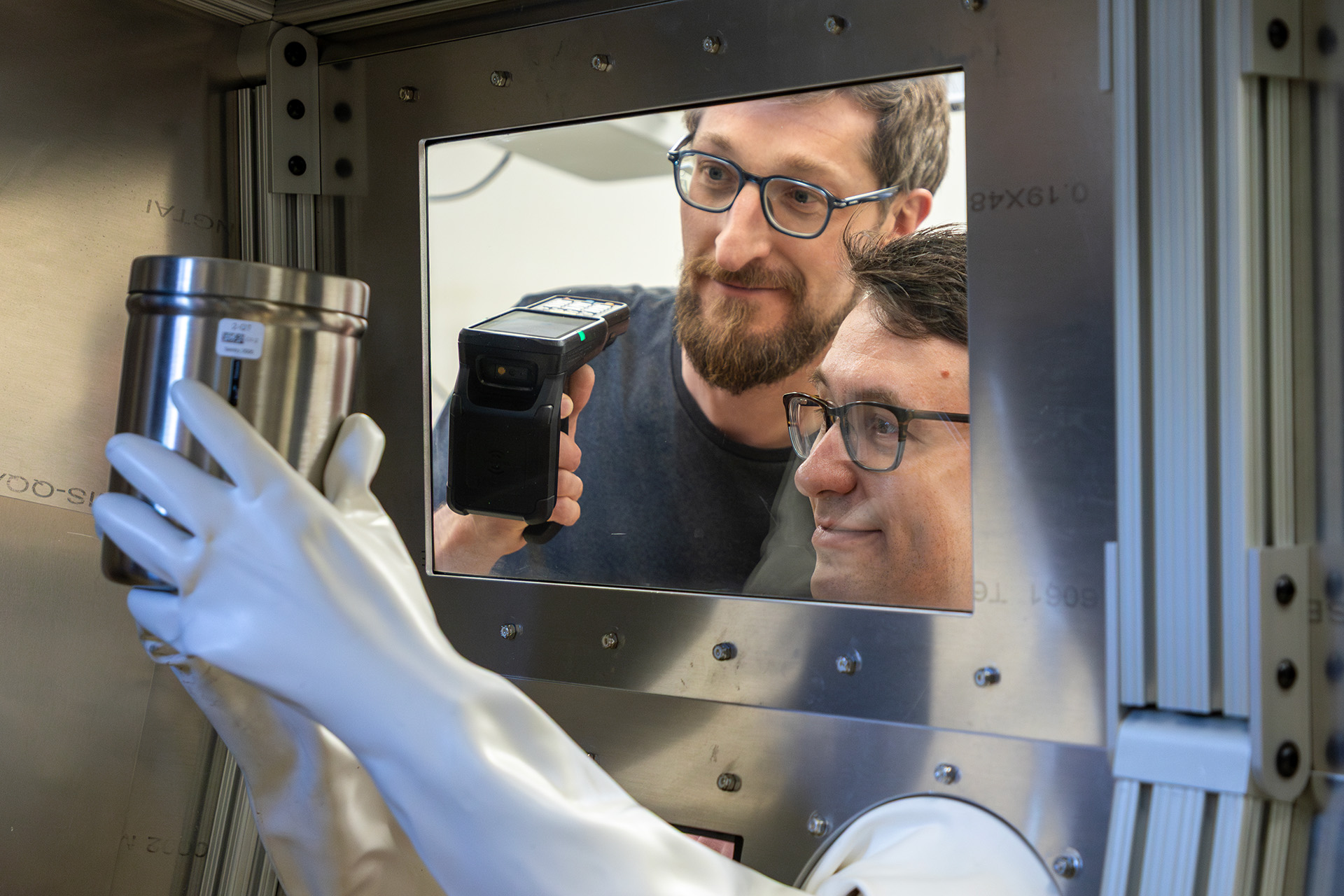

While earlier TES microcalorimeters served primarily as research tools, SOFIA—winner of an R&D 100 award in 2022—is specifically optimized for routine deployment in nuclear facilities. Its leap in precision is especially critical in high-throughput environments, where high fission product activity or strong background signals typically degrade performance in other types of detectors. Unlike previous experimental microcalorimeters, which were relatively bulky and relied on liquid cryogens for cooling, SOFIA’s remarkably compact, cryogen-free design allows it to be integrated into operational workflows, including use alongside gloveboxes and hot cells. It can also analyze materials in various forms (solid, liquid, or powder) and under diverse environmental conditions. SOFIA is easy to use, allowing robust, non-destructive testing with no need to open the sample container. The technology’s ultra-high resolution also allows hard-to-detect isotopes to be characterized by differentiating closely spaced gamma-ray peaks and detecting weak emission signals (e.g., the neptunium-237 86.5 keV peak, the uranium-238 113.5 keV peak, and the plutonium-240 104.2 keV peak).

How it works: SOFIA’s compound eye

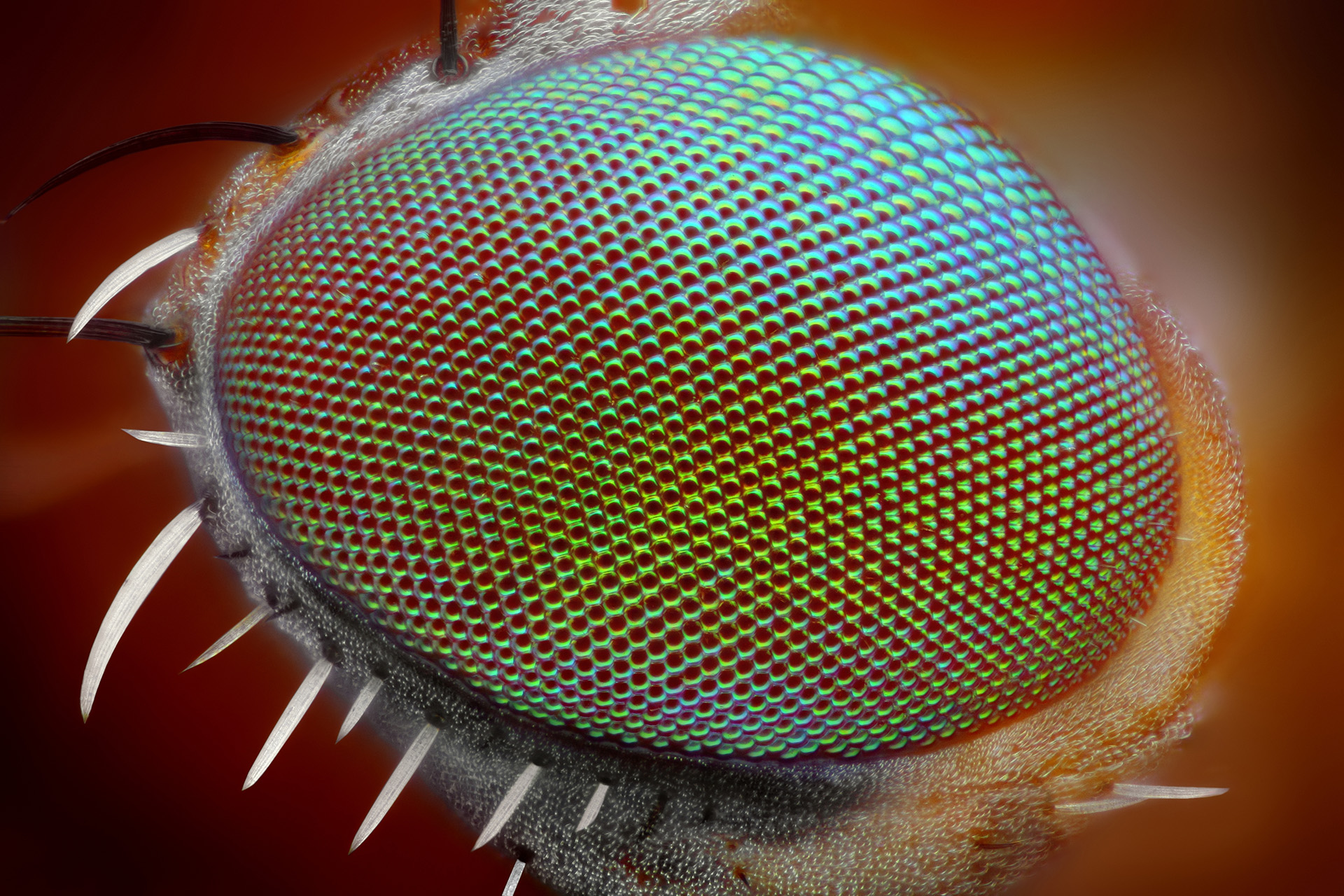

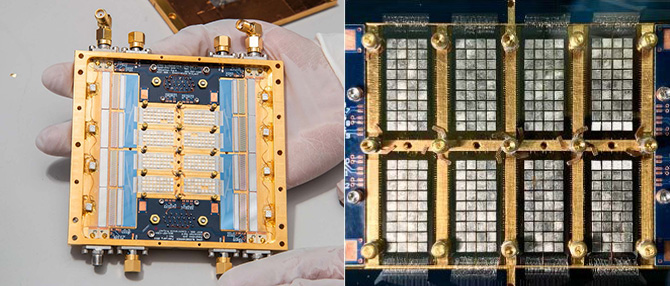

The TES technology on which SOFIA is based has been in development for several decades. It was originally designed for astrophysical applications—such as the detection of cosmic X-rays and gamma-rays from black holes, neutron stars, and supernovae—where exceptional energy resolution and low noise performance were achieved. These sensors measure minute gamma-ray emissions by converting their energy into heat pulses at cryogenic temperatures (~90 millikelvins), with each TES pixel in the array effectively acting as an independent microcalorimeter. The “eye” of SOFIA is therefore not a single sensor but an agglomeration of 256 spectrometers, all working in unison— somewhat analogous to the compound eye of an insect.

Each TES microcalorimeter in the array consists of three major components: a metallic detector, which absorbs gamma rays; the main TES (made from layers of normal and superconducting metals); and an amplifier. When cooled to cryogenic temperatures, the TES becomes superconducting but is poised on the limit of reverting to its normal (resistive) state—teetering on a sharp cliff edge. The smallest shove, in the form of a tiny wave of heat from the gamma ray photon (on the order of microkelvins), is enough to send it tumbling down the cliff, creating a change in its output of current. Because the gamma-ray signal is extremely weak, it must be boosted using a superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID)—a microchip-integrated amplifier capable of detecting current variations as small as a few femtoamperes.

Multiplexing: SOFIA’s FM radio

The next step of transmitting the detector signal to the readout electronics may seem like a small piece of the puzzle to a non-specialist. In reality, it poses a significant engineering challenge—critical to the system’s performance—because hundreds of individual detectors must be read out with ultra-low noise, minimal wiring, and at millikelvin temperatures. This is achieved using a technique called multiplexing, which combines many detector signals into a smaller number of readout channels. Minimizing the number of wires connected to room-temperature electronics is crucial because each wire to the cryogenic component carries heat, and there is a physical limit on how many coaxial lines one can fit into a cryogenic refrigerator.

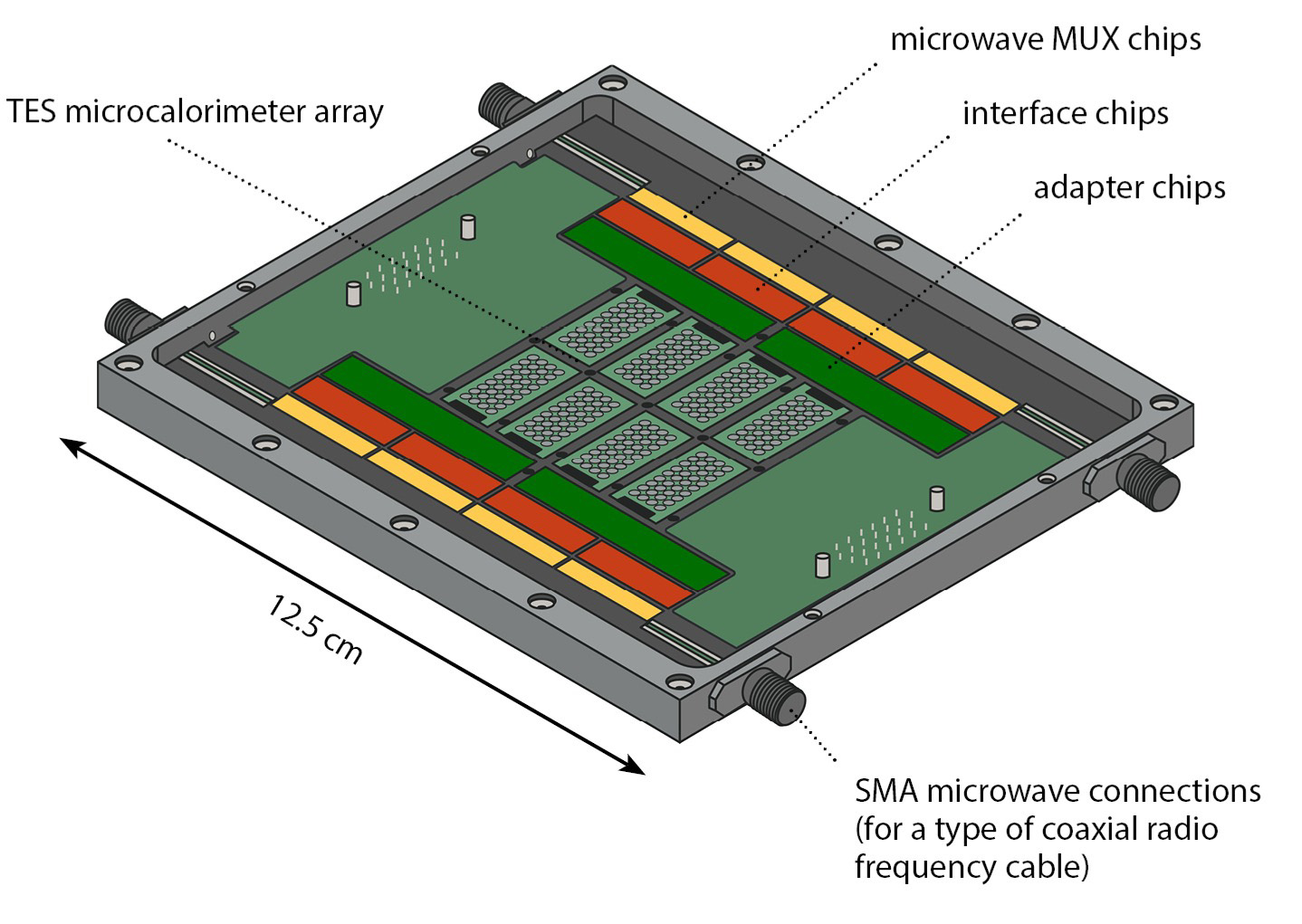

SOFIA evolved from an earlier prototype detector assembly, SLEDGEHAMMER (spectrometer to leverage extensive development of gamma-ray TESs for huge arrays using microwave multiplexed enabled readout), which provided a proof of concept for using microcalorimeters in nuclear material characterization (Fig. 1). SLEDGEHAMMER introduced key innovations in readout electronics and noise suppression, laying the foundation for SOFIA, which refined and optimized these advancements for deployment in facility environments.

According to SOFIA’s principal investigator Mark Croce, the innovations behind SLEDGEHAMMER and SOFIA stem from an improved multiplexing scheme: “One major advance that SLEDGEHAMMER introduced was time division multiplexing. This is like turning a selector switch to, say, I want channel 2 now and then it switches over to channel 2, channel 3, etc. and cycles through.” This implementation required all custom electronics, which were expensive and less advanced compared with field programmable gate arrays (FPGAs)—integrated circuits sold off-the-shelf. Croce continues: “The current version of SOFIA is essentially like FM radio. So, every channel, every sensor in the detector array has its own unique carrier frequency that it modulates. The firmware in our FPGAs is recording all of those signals simultaneously and separating them by the known resonator frequency.”

This innovation was essential to achieve high count rates (up to 5,000 counts/ sec), enabling measurement times comparable to those of HPGe detectors, while also allowing for a more compact instrument than previous TES-based microcalorimeters. Using SOFIA, the uranium-235/plutonium-239 ratio (an important yardstick in mixed-oxide nuclear fuels) can be determined with a 1-sigma precision of below 1.0% in hours (compared to several percent for an HPGe detector running for the same time).

Croce’s team plans to incorporate the latest generation of readout electronics into SOFIA’s next iteration. “These electronics were developed as part of the huge commercial investment in the digital electronics for gigahertz communications,” Croce says. “This has allowed us to move most of the complexity of the previous custom superconducting SQUID chips into firmware. This is on a commercially purchased hardware platform, so the custom part is the firmware for the readout and the software to run it.”

SOFIA does not serve as a blanket replacement for HPGe detectors—it is optimized for facility applications, and despite being compact for this type of TES microcalorimeter, it remains a much larger instrument than a germanium detector. Croce admits, “It does have unique capabilities, but you know, not everybody needs a race car—there's a lot that you can do with conventional germanium detector.”

Cooling

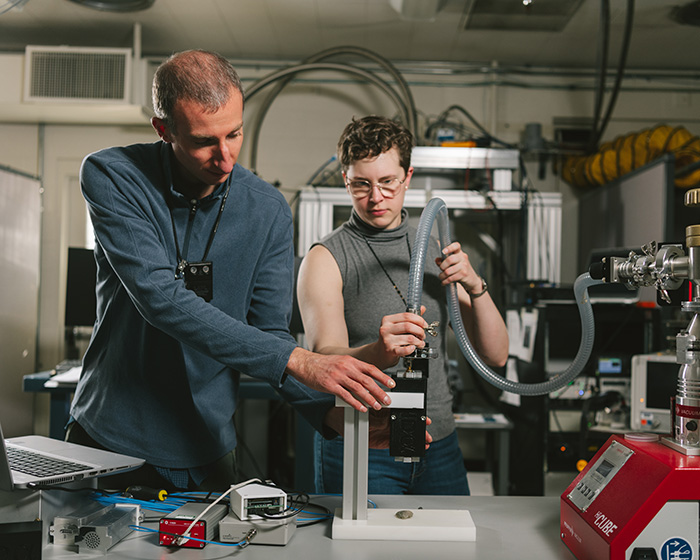

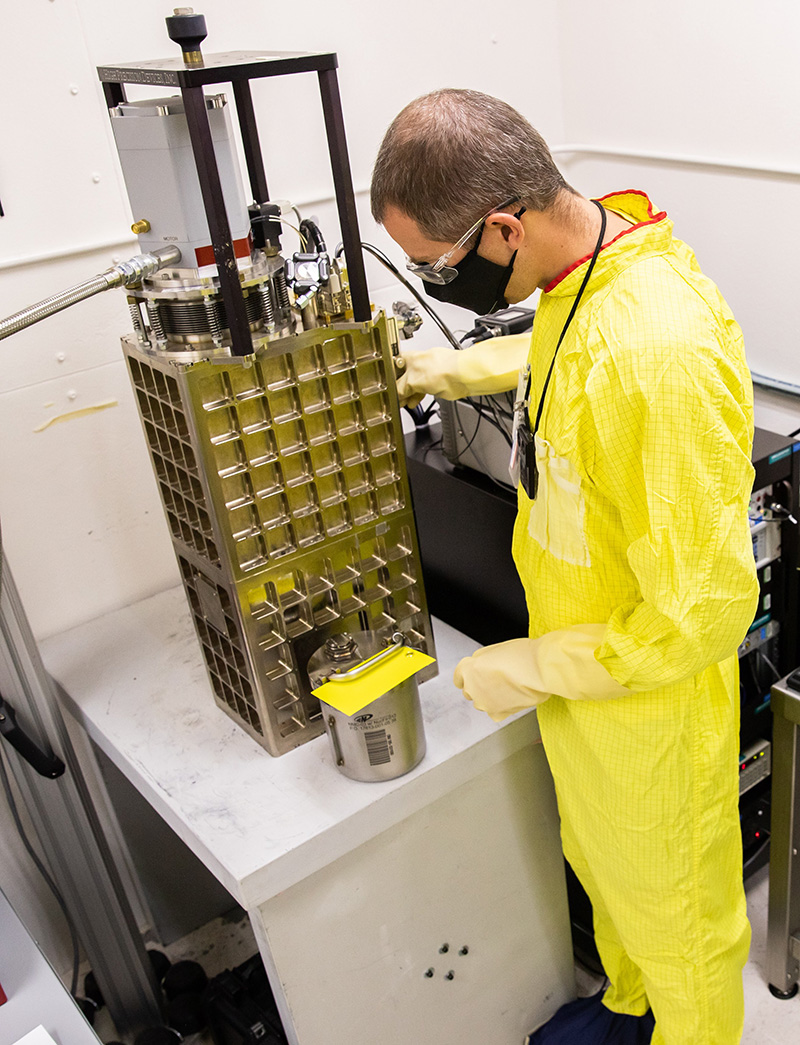

Typically, reaching ultralow superconducting temperatures requires either liquid helium or a large pulse tube refrigerator, which in turn requires three-phase power and a cooling water supply. One of SOFIA’s key innovations is its use of a compact, tabletop cryostat that operates from a standard 220 V outlet, making it relatively easy to deploy in a nuclear facility (Fig. 3). However, Croce acknowledges that despite this progress, further refinement is needed to close the performance gap between SOFIA and conventional HPGe detector systems. A promising development in this area comes from recent cryogenic technology advances, particularly a new pulse tube cryo-cooler on the market that uses about half the power. This improvement could eventually allow SOFIA to run on a regular 120 V power source, much like HPGe detectors.

A 400 pixel eye: HERMES flies to other national labs

After the first iterations of SOFIA were developed, attention turned to expanding the TES array—in principle, increasing the number of detector pixels could yield further performance gains. In 2022, HERMES (high efficiency and resolution microcalorimeter emission spectrometer) was developed, featuring a 400 pixel detector that employs the same multiplexed architecture as SOFIA. It has already been deployed in nuclear facilities at the Idaho and Pacific Northwest national laboratories (Fig. 4).

True to its namesake, the swift-footed Greek god, HERMES transmits its data rapidly, with the expanded pixel array enabling high-quality results in less time. Croce says, “If we can reduce the measurement time and still get this excellent precision and accuracy on the isotopic composition, that has huge practical benefits. For instance, in the plutonium facility, they have a lot of material accounting measurements to run through, which is often a bottleneck in facility operations.” (see Atomic Management: The DYMAC 2.0 Initiative for more information).

A less practical aspect of HERMES is its large cryostat, which is intended for permanent use in an analytical laboratory. However, Croce says, “We are actually looking at the next generation of SOFIA to use the same detector arrays and we think we can get close to 400 pixels in a SOFIA-type instrument with the small cryostat that can be used in multiple facilities.”

Getting SAPPY

Advances in pulse processing and computational isotope analysis have also benefitted SOFIA and HERMES. These instruments use SAPPY (spectral analysis program in Python) as its primary software tool for analyzing gamma-ray spectra and determining isotopic ratios, which is seamlessly integrated into the operation of the instrument. It can perform isotopic analysis for both microcalorimeter data and traditional detectors like HPGe, allowing direct comparisons between instruments. Along with cross-detector compatibility, SAPPY’s enhanced uncertainty modeling, improved peak fitting, and handling of high-resolution data make it very effective for interpreting complex spectra with overlapping peaks, a common real-world challenge in noisy radiation environments. This has allowed SAPPY to deliver results more quickly by automating the spectrum processing.

Outlook

Development of SOFIA and other prototypes began in the late 2010s, led by a team at Los Alamos in the Safeguards Science and Technology group. They were joined by researchers from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), who provided expertise in microcalorimeter technology and spectrometer design, and by collaborators from the University of Colorado Boulder, who contributed to the design and testing phases. Key to this work was the support of the DOE Office of Nuclear Energy's Material Protection, Accounting, and Control Technologies (MPACT) program and University Program (NEUP), which has prioritized enhancing the performance of microcalorimeters for gamma-ray spectroscopy. The team has since drawn interest from several commercial nuclear reactor developers, who view this next-generation NDA technology as a critical enabler for their advanced nuclear systems. SOFIA offers the potential for lower-cost material accounting measurements, helping to meet licensing and process-monitoring requirements for emerging nuclear reactor designs.

The Low Temperature Detectors Team consists of Mark Croce, Matt Carpenter, Kate Schreiber, Daniel McNeel, Rico Schoenemann, Emily Stark, Shannon Kossmann, Hyrum Hansen, Sophie Weidenbenner, Katrina Koehler, Tim Ockrin, Stefania Dede, Christine Mathew, and Cameron Wojtowicz.