Tracking Nuclear Materials Using RFID

- Jake Bartman, Communications specialist

At Los Alamos National Laboratory, workers support the nation’s nuclear security enterprise by producing the plutonium pits that are the cores of the United States’ nuclear weapons. Although the Laboratory has produced limited quantities of pits since its founding in the 1940s, the US has lacked the capacity to manufacture pits at scale since the Rocky Flats Plant ceased pit production in 1989.

In October 2024, Los Alamos completed its first production unit—the first pit to meet the National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA’s) requirements for acceptance into the nuclear stockpile since the Laboratory produced some 30 pits in the 2000s. This achievement was a key step toward reaching the NNSA’s target of producing, by 2030, no fewer than 30 pits per year at Los Alamos—an accomplishment that required developing and deploying modern techniques that will make pit production safer, more efficient, and more sustainable than it was at Rocky Flats.

Despite these accomplishments, for decades, little has changed in how the Laboratory tracks and accounts for the special nuclear material and other assets used in pit production. Today, as in years past, workers in PF-4 (the Laboratory’s Plutonium Facility) conduct inventories with a clipboard and pen in hand before manually entering counts into a database. Periodically—often twice per year—production must be paused altogether while workers perform inventory reconciliations that can take 35 to 70 days apiece. To help modernize the inventory process, as a part of the DYMAC (Dynamic Materials Accountability System) 2.0 initiative, a team of researchers began evaluating RFID (radio frequency identification) systems for implementation in PF-4—a technology that could revolutionize asset tracking in the facility (for more information about DYMAC 2.0 see Atomic Management: The DYMAC 2.0 Initiative).

“There are a lot of activities and projects in Weapons Production that are doing manual inventories,” says Ray Ferry of Los Alamos’ Production Analysis and Transformation group, which works to bridge current and future production techniques and practices with those that have historically been conducted in the nuclear enterprise. “It’s just the way we’ve always done it. But we have to change.” More efficient inventory operations would allow for better use of spaces and labor resources.

“There are a lot of activities and projects in Weapons Production that are doing manual inventories. But we have to change.” — Ray Ferry, Production Analysis and Transformation.

Overcoming security challenges

When DYMAC 2.0 was created, the program initially focused on developing nondestructive assay tools to measure nuclear materials in PF-4, reducing the need to pause production and conduct inventory reconciliations. RFID was dismissed as part of this work, however.

“As modern asset management systems were being envisioned, RFID was almost discounted because there had been almost 20 years of activity at the Laboratory with no substantive progress toward meeting security requirements,” Rollin Lakis, the leader of the DYMAC 2.0 initiative, says. “But technology has advanced dramatically in the RFID community. We soon recognized that these technologies would provide such an enormous benefit to the mission that we needed to invest into that R&D portfolio, to overcome security and technical barriers for implementation.”

The RFID research team has had to overcome substantial challenges to bring RFID into PF-4. In addition to stringent security requirements, much of the work completed in the facility involves material that is hazardous and potentially of high consequence. Every step of the process of developing and incorporating an RFID system must be rigorously evaluated to ensure the system’s accuracy and reliability—there’s no room for error.

And yet, the goal of implementing RFID into PF-4, which seemed fanciful only a few years ago, is on its way to being achieved, with four RFID pilot programs slated to take place inside TA-55 (which includes PF-4) in fiscal year 2025. Beyond tracking material in the facility, the RFID team’s work has opened doors to ways in which RFID could bolster many aspects of PF-4’s mission beyond asset tracking. These opportunities will help make the facility safer, more secure, and more productive.

“Technology has advanced dramatically in the RFID community… [and] would provide such an enormous benefit to the mission.” — Rollin Lakis, Safeguards Science and Technology.

RFID 101

RFID is everywhere: in contactless credit-card readers, transportation toll collection, airplane components and operations, retail apparel, and more. Although it is possible to trace RFID’s origins to the World War II–era development of radar, RFID, as we understand the technology today, wasn’t developed until the 1970s. It entered the commercial marketplace in the 1980s and rolled out to multiple industries in the 1990s. Today, RFID is even more widespread with an estimated 40 billion RFID tags placed on assets just in 2024.

At its most basic, an RFID system comprises three components: tags (which are placed on or inside an object to be tracked), readers (which interact with the tags to gather their location and other information), and a backend system (which tracks and processes data). RFID technologies can be divided into three classes—active, passive, or semi-passive—based on how the tag and the reader interact.

In active systems, battery-powered RFID tags intermittently transmit signals across distances up to hundreds of feet. By contrast, in passive RFID systems, the tags have no internal power source; the reader emits an electromagnetic field that powers an integrated circuit or microchip in the tag. Passive systems, featuring tags that are typically 10–100 times less expensive than those used in active systems, have a shorter range than active ones (passive systems’ range is typically limited to just a few feet). Active systems can also operate at higher frequencies (into the microwave band).

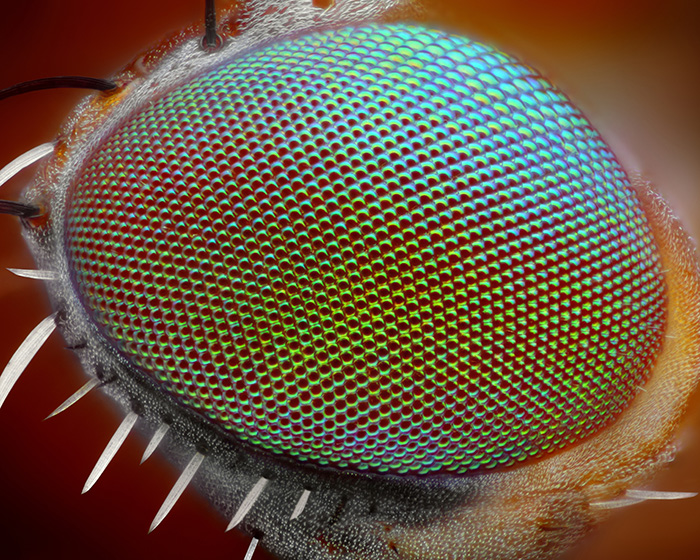

A key first step in deploying RFID, therefore, is determining the right type of system for a given use. At Los Alamos, the RFID team is deploying a passive ultra-high frequency (UHF) system, which has promising characteristics for tracking assets in nuclear facilities (Figs. 2 and 3). Passive UHF systems enable tracking within a few feet from the assets, their readers and tags are relatively inexpensive, and the tags are durable and can withstand radiation levels typically found in most parts of the plant. UHF RFID systems’ decades of use means that they are a mature technology with well-accepted and maintained standards.

Expanding RFID’s capabilities

One promising idea involves deploying stationary RFID scanners at doorways to automatically track the movement of material into and out of rooms. The research team is also exploring the possibility of deploying real-time asset tracking that would allow operators to see, on a map, where materials are. “This is particularly useful if you want to locate an asset in the facility and send an operator to inspect the asset—to make sure that it is where it’s supposed to be and in the condition that it’s supposed to be in,” says Alessandro Cattaneo (of the Mechanical and Thermal Engineering group), who leads the DYMAC RFID team.

However, radio waves can reflect off the surfaces of metallic objects, complicating the use of RFID in gloveboxes. This problem is compounded when nuclear material containers are pushed together in clusters, for instance when glovebox operators need some extra elbow room to maneuver, and also by the limits imposed on RFID power settings due to security constraints in PF-4.

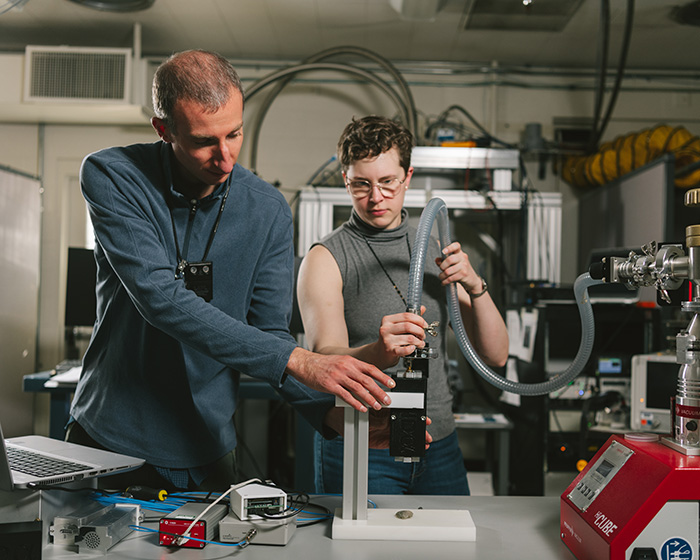

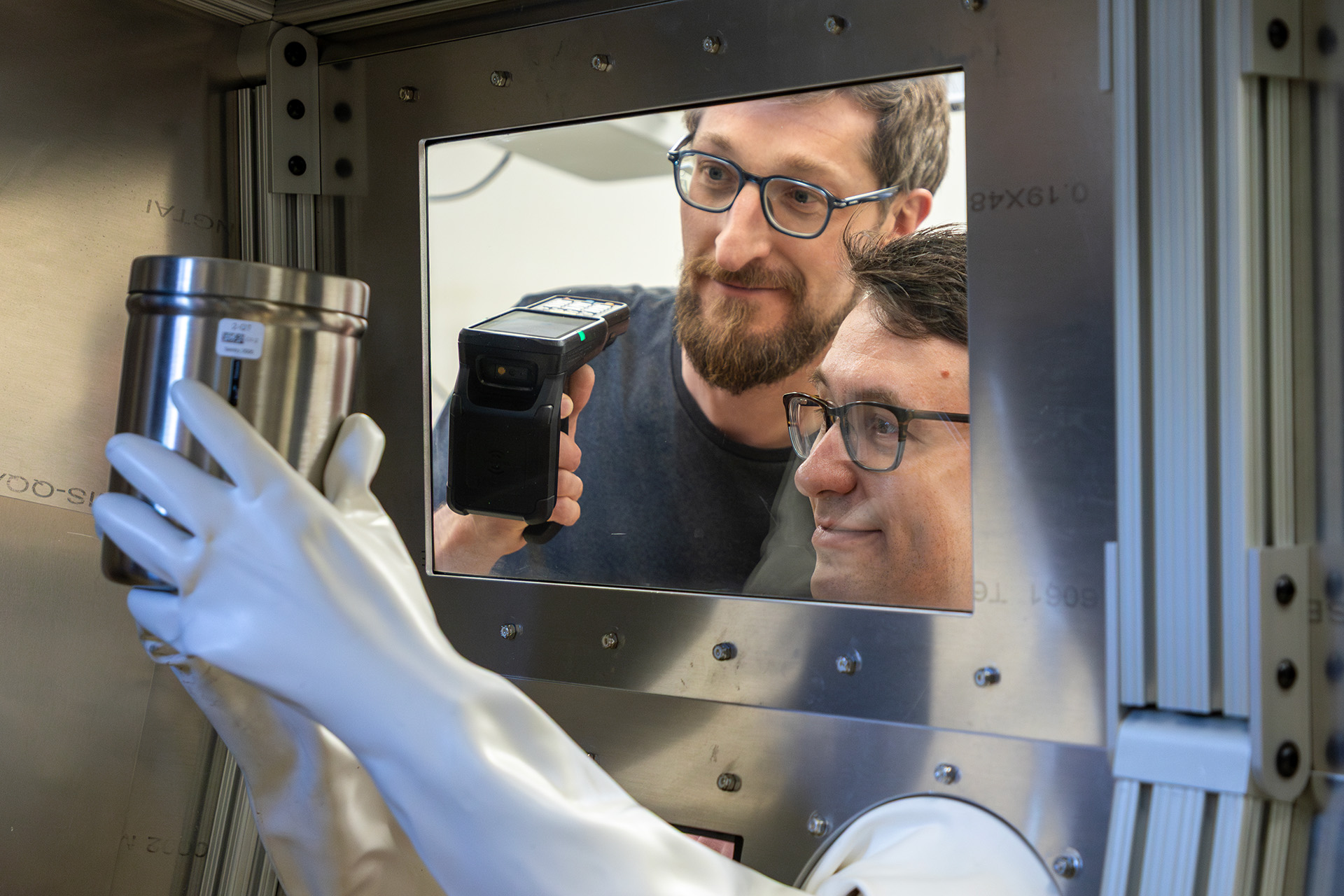

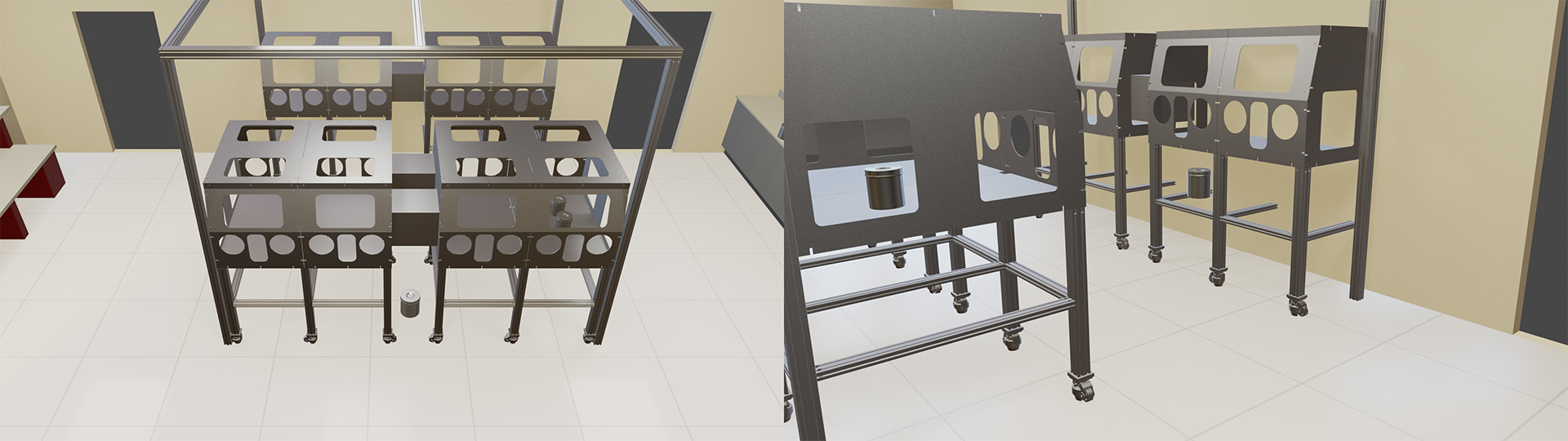

To help understand these systems and their limitations, the team created an RFID laboratory as a testbed that contains several mockup gloveboxes and a collection of empty nuclear material containers. This made it possible for researchers to evaluate the variables that affect RFID performance in a controlled environment.

The research team has collaborated closely with the Laboratory’s Statistical Sciences group, who have taken a rigorous statistical approach to determining the tags’ performance and establishing a performance baseline—an important consideration at a time when RFID tools are evolving constantly, with different tools providing different levels of performance. Other internal collaborations have developed models to capture the propagation of RF waves and helped modify off-the-shelf software to reprogram the handheld readers and expand functionality. The goal is to design tools that can be optimized, without resorting to trial and error, for distinct environments.

To support real-time tracking of material in the facility, Allison Davis (of the Mechanical and Thermal Engineering group) has created a tool that will allow operators of the RFID system to visualize data in a photorealistic way (Fig. 5). The software, which is based off a game engine, allows users to follow the movement of assets through a room—something that has proven especially useful in helping operators to understand the relationship between assets and the environment.

Brendon Parsons, the RFID subject matter expert in the Safeguards Science and Technology group, notes that RFID is versatile enough that with careful engineering, it is possible to design systems that go beyond asset tracking. “RFID can also be used to communicate data,” Parsons says. “For example, there are RFID tags that are able to measure temperature and humidity, and interface with microcontrollers.” In turn, these microcontrollers could connect with precision equipment inside gloveboxes, allowing for continuous monitoring of the glovebox environment.

Tamper-indicating devices

A promising application is incorporating RFID tags into tamper-indicating devices, or TIDs. TIDs can be used to control and protect nuclear material by making it clear to operators when there has been unauthorized access to a container. Although some TIDs are available commercially, these technologies don’t necessarily meet the Laboratory’s requirements. For that reason, the RFID team has also evaluated the possibility of additively manufacturing RFID-enabled TIDs at scales that could support the Laboratory’s production mission by helping operators follow material throughout a dynamic production environment.

“This is a very disciplined operation,” says Arnold Guevara, former leader of the Safeguards division, which works to track and protect nuclear material in PF-4. “You have to know the material, its weight, its location, and so on. It would be easier if the material was static, but that’s not the case.”

Guevara says that current TIDs suffer certain shortcomings. For one thing, like other items in the facility’s workflow, TIDs must be tracked manually. Moreover, the materials used in TIDs can degrade over time. “Developing TIDs with embedded RFID would save a lot of effort,” he says.

The research team has been collaborating with Auburn University, which has a renowned RFID research and development program, to develop RFID technologies that meet the Laboratory’s needs. “We didn’t want to reinvent the RFID wheel, and we recognized their experience, so we collaborated with them,” Ferry says. “We want to benefit from what private industry is doing and look at what technology would work in our environment.”

Ferry says that Auburn has helped the Laboratory to establish testing requirements for its RFID technologies. The university is also helping Los Alamos to determine standards for RFID tags that then might be manufactured by industry partners. The collaboration has brought Auburn students to Los Alamos, some of whom are working to help identify tags that meet the Laboratory’s standards (and some of whom Los Alamos has hired).

The budget for the RFID project has grown substantially since it was launched in the middle of 2021, and the program now receives around $3 million per year in funding (with DYMAC 2.0 garnering some $5 million). Encouragingly, the project recently received additional funding from the NNSA’s Office of Information Management to help to move RFID toward implementation in PF-4: In fiscal year 2025, four pilots are planned for PF-4.

Summary

Recent advancements in RFID technology, previously overlooked in PF-4 due to insufficient security features, now hold the potential to transform the accountancy of nuclear materials. Furthermore, these systems could also bolster safety and production quality—they can be used, for instance, to support in-situ process monitoring, ensuring that only materials that meet quality standards are advanced through the production process. The potential for RFID continues to grow, with other novel applications on the horizon. But the fundamental goal of implementing RFID in PF-4—to support nuclear material control and accountability—remains the same. “The name of the game is to increase production while lessening the burden on operators and ensuring compliance,” Guevara says. “It is a team effort.”