NDA Instruments of the Safeguards Training Program

- Owen Summerscales, Editor

Nondestructive assay (NDA) instruments are widely used in industries such as aerospace, materials science, oil and gas, and construction, where they are employed by engineers to interrogate the structure of a material without affecting its composition. These instruments also find a very important application in the nuclear industry—particularly in nuclear material accounting and control (NMAC) and inspections—as the radioactive signatures of nuclear materials makes them amenable to a range of NDA techniques. These methods preserve the integrity of the sample, minimize health and safety risks in hazardous environments, and provide rapid, often real-time results.

Types of NDA methods for determining properties of nuclear materials include neutron-based techniques, gamma ray spectroscopy, X-ray fluorescence, calorimetry, radiography, ultrasound and acoustic methods, laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy, and surface analysis. Today, the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) routinely uses dozens of NDA systems, the majority of which were pioneered at Los Alamos National Laboratory. This article provides a technical overview of the primary techniques taught to inspectors in the Los Alamos Safeguards and Security Technology Training Program (SSTTP; see 50th Anniversary of the Safeguards and Security Technology Training Program for an overview of the course).

1. Gamma-ray spectroscopy

Gamma rays are the highest—and most damaging—energy form of electromagnetic radiation, with photon energies ranging from hundreds of keV to several GeV. They are emitted by radioactive decay at energies that are unique to specific isotopes, making the distribution of gamma ray frequencies an effective fingerprint for isotope identification. By measuring the intensities of the energies, the abundance of various isotopes in a given sample can then be further calculated.

For the measurement of gamma rays—both inside and outside of safeguards applications—there are several types of detectors:

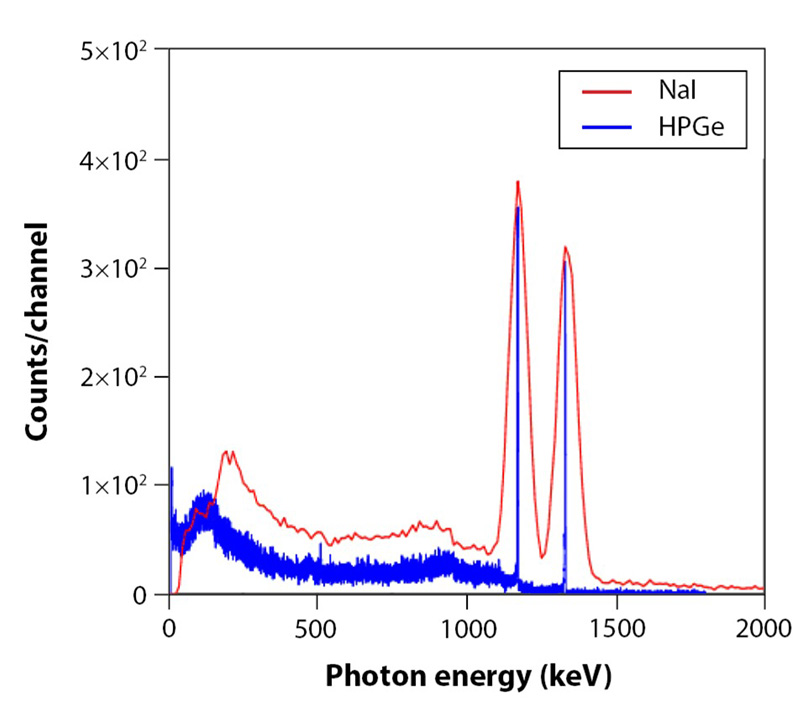

- Inorganic scintillators, e.g., sodium iodide (NaI). These materials fluoresce when exposed to gamma rays, producing pulses of light that can be analyzed.

- Semiconductor (solid-state) detectors, e.g., high purity germanium (HPGe). Gamma rays ionize these materials, creating electron-hole pairs that convert the energy of the gamma rays into an electrical current, which is measured.

Additionally, outside of the scope of the SSTTP:

- Gas-filled detectors, e.g., Geiger counters. A volume of gas is ionized by gamma rays and creates an electric current between two electrodes. These detectors are not frequently used in safeguards applications because they lack the spectroscopic resolution needed in the energy range typical for uranium and plutonium (approximately 100–1,000 keV).

- Microcalorimeter detectors, e.g., SOFIA (see From Starlight to Safeguards: The SOFIA Gamma-Ray Spectrometer). Currently in the research and development phase, these highly sensitive devices are capable of generating extremely high-resolution spectra by utilizing material properties at ultra-low temperatures, below 0.1 K.

1.1 Inorganic scintillators

A scintillation detector consists of a scintillator crystal, photodetector, and a circuit for measuring the pulses from the photodetector. A typical output plots energy (or “channels”) versus counts. Scintillator crystals that are best suited for the detection of gamma rays contain absorbing atoms with high atomic number (high-Z materials), which are usually doped with an impurity to help release the absorbed energy. When the material absorbs a gamma ray, it excites an electron from the valence band into an excited state, creating an electron-hole pair—this pair moves around the crystal lattice until it finds an impurity center, where it can relax and release the energy as scintillation photons that can be counted.

Thallium-doped sodium iodide is by far the most commonly used scintillator material and finds wide applications in nuclear NDA (as well as in fields such as crystallography, where it has been foundational). It was first discovered in 1948, ushering in the field of inorganic scintillation X-ray and gamma spectroscopy, and remains popular due to its extremely good light yield, high stopping power (thanks to high-Z element iodine), and excellent linearity. More recently, the IAEA has switched to using more expensive cerium-doped lanthanum tribromide due to its better energy resolution.

The first ever electronic scintillation counter was built by Curran and Baker in 1944 during the Manhattan Project to detect alpha emissions from uranium. They used a zinc sulfide scintillator and the newly available photomultiplier tube to obtain a record of electrical pulses that could be subsequently analyzed, giving reliable measurements of uranium. Previously, counting these scintillations had to be laboriously performed by eye using a special type of microscope.

1.2 Semiconductor detectors

Semiconductor detectors made from high purity germanium (HPGe) offer a significant increase in energy resolution over sodium iodide scintillators, which, despite their many advantages, give very broad gamma-ray peaks by comparison (Fig. 4). This means that closely spaced peaks cannot always be resolved with scintillator detectors, making them unsuitable for complicated mixtures of materials or with elements that have multiple isotopes and emit many gamma energies. The germanium crystal used in HPGe detectors is extremely pure—in excess of 99.999999999%. This is far beyond the purity of typical semiconductor-grade materials, as even trace impurities can dramatically degrade detector performance.

HPGe detectors comprise a semiconducting diode directly connected to a circuit: upon absorption of a gamma ray, an electron-hole pair is created in a similar manner as in a scintillator material. Under the influence of an electric field, the electron-hole pair travels to the electrodes, giving a measurable electric pulse. One disadvantage of these detectors is that they must be cooled to cryogenic temperatures—at room temperature, thermal excitation causes excessive noise and destroys energy resolution. The need for cooling therefore makes them more expensive and less portable.

A new type of detector being considered by the IAEA (and slated to be included in the SSTTP training course) is the CZT (cadmium-zinc-tellurium) detector, which offers similar performance to HPGe instruments but without the need for cryogenic cooling.

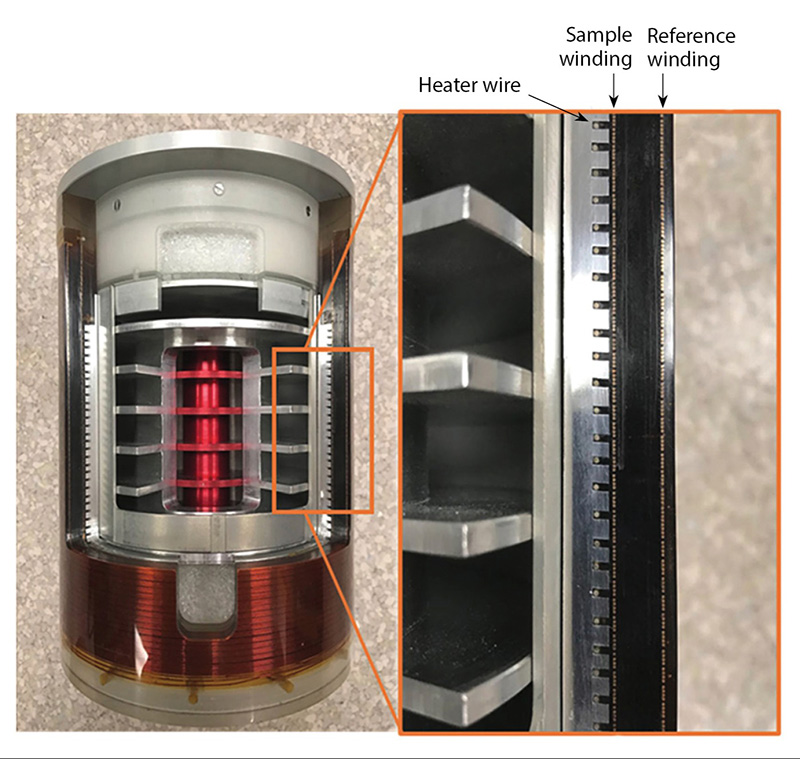

2. Calorimetry: Quantification through heat

Calorimetry is an alternative and complementary assay method for gamma ray detection, being simpler and more robust than spectrometry, and useful for environments where total energy output is the primary concern. Gamma radiation produces heat when it hits a sensor, and by quantifying this thermal power, an accurate mass measurement of the isotope can be obtained. The main prerequisite is that the half-life of the radioisotope must not be either too short (producing an inconsistent heat output) or too long (producing too little heat to measure on a practical timescale). For safeguards purposes, this prerequisite is met by most of the common plutonium isotopes (plutonium-238, -239, -240, and 241), tritium, and americium-241. Uranium-235 and -238 decay too slowly for quantification via standard calorimetry.

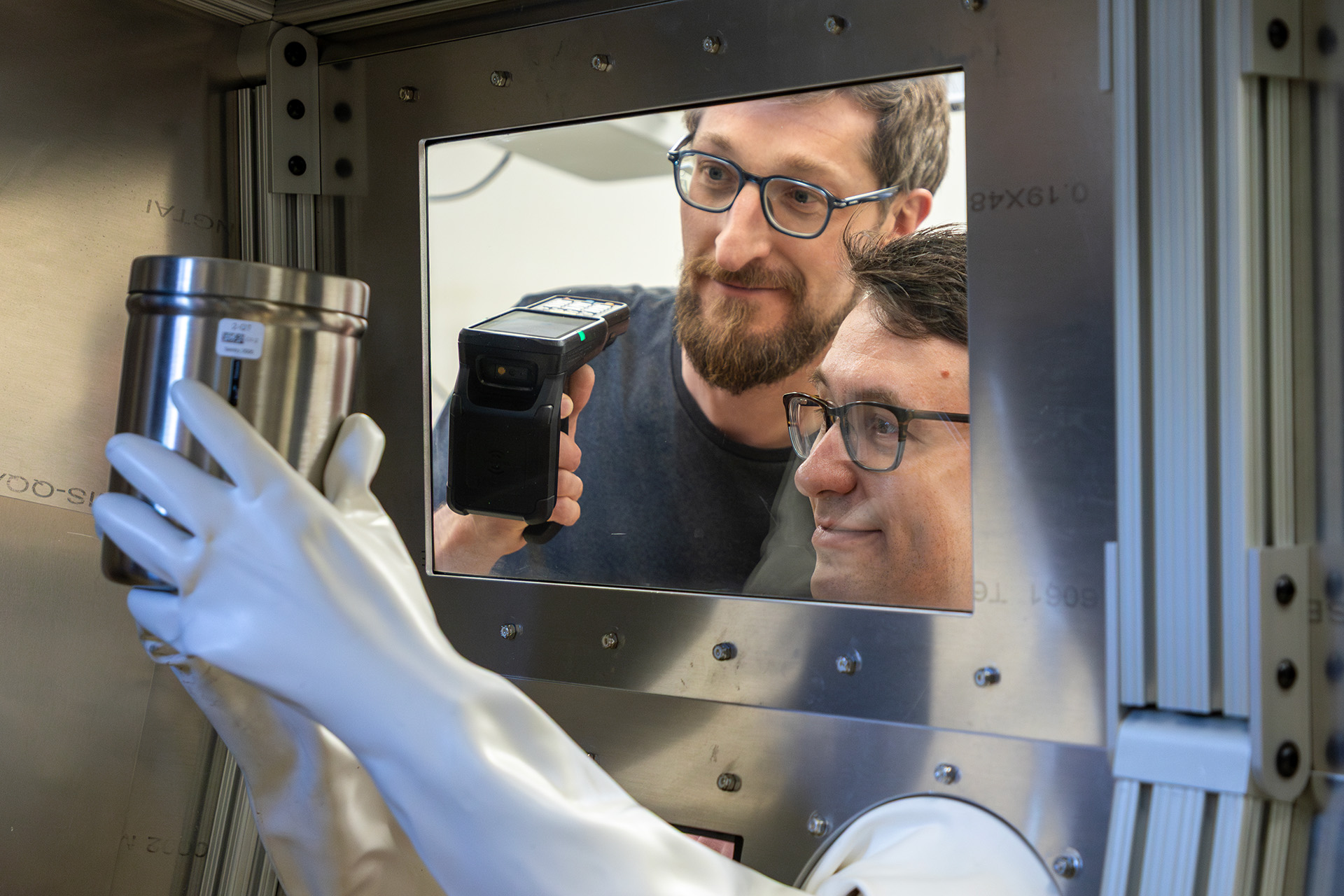

Calorimetry is a simple and accurate technique and is widely used in the nuclear industry to account for plutonium in fuel pellets, powders, and metals, often obtaining the highest precision and accuracy of all NDA methods. It focuses on the total energy absorption rather than resolving individual gamma-ray energies and can also be used to quantify radiation dose. Because calorimetry cannot detect isotopic signatures, it cannot be used alone for plutonium and needs to be combined with a method of determining isotope ratios—typically, gamma spectroscopy or mass spectrometry. In some situations, for instance large items where the use of gamma spectroscopy is limited, or when quicker analysis is needed (calorimetry measurements typically take 1–8 hours), neutron-based methods are used. Plutonium also often contains varying amounts of americium-241, a heat-producing decay product, that needs to be accounted for.

3. Neutron counting techniques

Neutrons, being electrically neutral, can only be detected indirectly from their interactions with matter. These interactions generate charged particles—such as alpha particles, protons, and positrons—as byproducts, which produce electrical signals that are picked up by the detection system. Due to the nature of these neutron-induced reactions, detectors generally offer limited energy information, providing the number of neutrons detected rather than their energy. As a consequence, many neutron detecting systems are referred to as counting methods. The raw count rate is referred to as “singles” neutron counting, which is used to distinguish it from more sophisticated coincidence and multiplicity measurements, discussed below.

Neutron-based detection techniques are very powerful and include a range of basic methods that count the number of neutrons emitted spontaneously, such as passive neutron counting. In addition, more complex techniques can be employed, including active neutron interrogation, which uses additional neutron sources to induce fission events. Many of these techniques rely on helium-3—an expensive material—used in neutron proportional counters, and involve bulky, specialized equipment that is often deployed alongside previously described methods such as gamma ray spectroscopy.

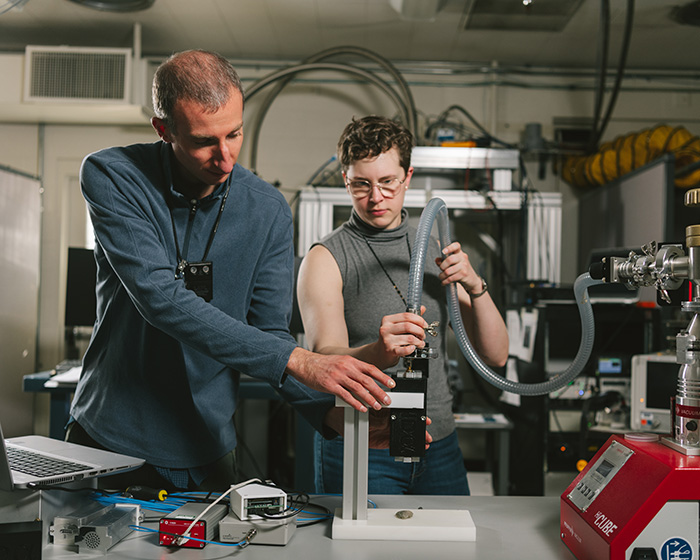

Three important transportable neutron counting instruments covered by the SSTTP are the high-level neutron coincidence counter (HLNC), the active well coincidence counter (AWCC), and the uranium neutron coincidence collar (UNCL), described below. In the training course, participants get a hands-on learning experience with all of these instruments, which were originally designed at Los Alamos in the 1970s and 1980s specifically for safeguards inspection.

Counting techniques for plutonium: 240 is the magic number

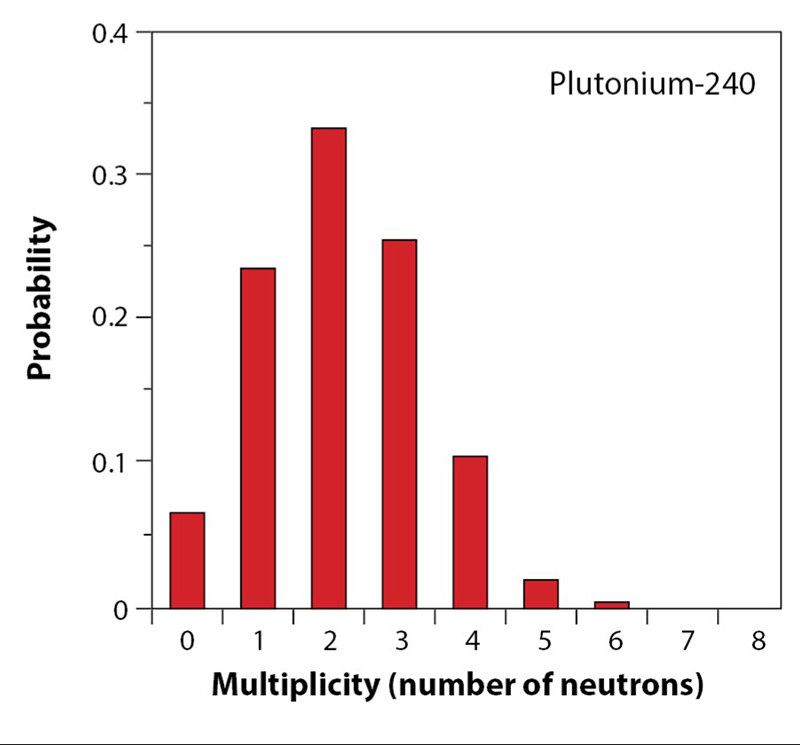

Spontaneous fission is the primary NDA signature and assay method for plutonium—a typical sample of plutonium metal emits approximately 100–400 neutrons per gram per second. This process occurs exclusively in the even-numbered isotopes of plutonium—238, 240, and 242—with plutonium-240 being the dominant contributor due to its high abundance in a typical sample of plutonium metal, making it the key isotope for analysis.

One of the complications of passive neutron counting is caused by (α,n) reactions, which occur when light elements absorb alpha particles. These light elements can include oxygen present in oxides or hydrocarbons found in packing material. The (α,n) neutrons that come from these reactions can be a significant source and difficult to differentiate from the primary fission neutrons, if one is only counting the total number of neutrons detected.

A solution to this problem can be arrived at by looking at the time distribution of neutron detections: spontaneous fission produces bursts of time-correlated neutrons (Fig. 7 shows the probability distribution of the number of neutrons in each burst for plutonium-240), whereas emission from (α,n) reactions creates individual, uncorrelated neutrons at random. With this knowledge, a method called coincidence counting uses statistical analysis methods to count the pairs of correlated neutrons which can only be produced from fission events. The “doubles” count is the number of coincidence events where two neutrons are detected within a defined time window (usually microseconds)—which indicate neutrons from the same fission chain or event.

For plutonium, coincidence counting can be used to yield an effective mass of plutonium-240, which can be taken in combination with a method to determine the isotopic distribution, such as gamma ray spectroscopy, to give the total plutonium mass in the sample. Neutron coincidence counting is widely used in international safeguards inspections to certify conventional nuclear fuels. However, its application in domestic accountability measurements has been more limited due to the potential for error when the technique is improperly applied to impure materials.

Impure samples such as mixed-oxide (MOX) fuels that contain large amounts of neutron moderating or scattering materials cannot be accurately measured using the standard coincidence counting technique. In these cases, a method known as neutron multiplicity counting can be used to get a more accurate answer than coincidence counting can provide. In the coincidence counting method, only the correlated pairs of neutrons are measured, but in multiplicity counting, the correlated triples (i.e., three neutrons in a short timeframe) are measured. Using this added information, the multiplicity method solves a system of equations known as the “point model equations” to explicitly solve for the mass and level of impurity in the item. The neutron multiplicity counting method gives a more accurate answer than coincidence counting when unknown amounts of impurity are present.

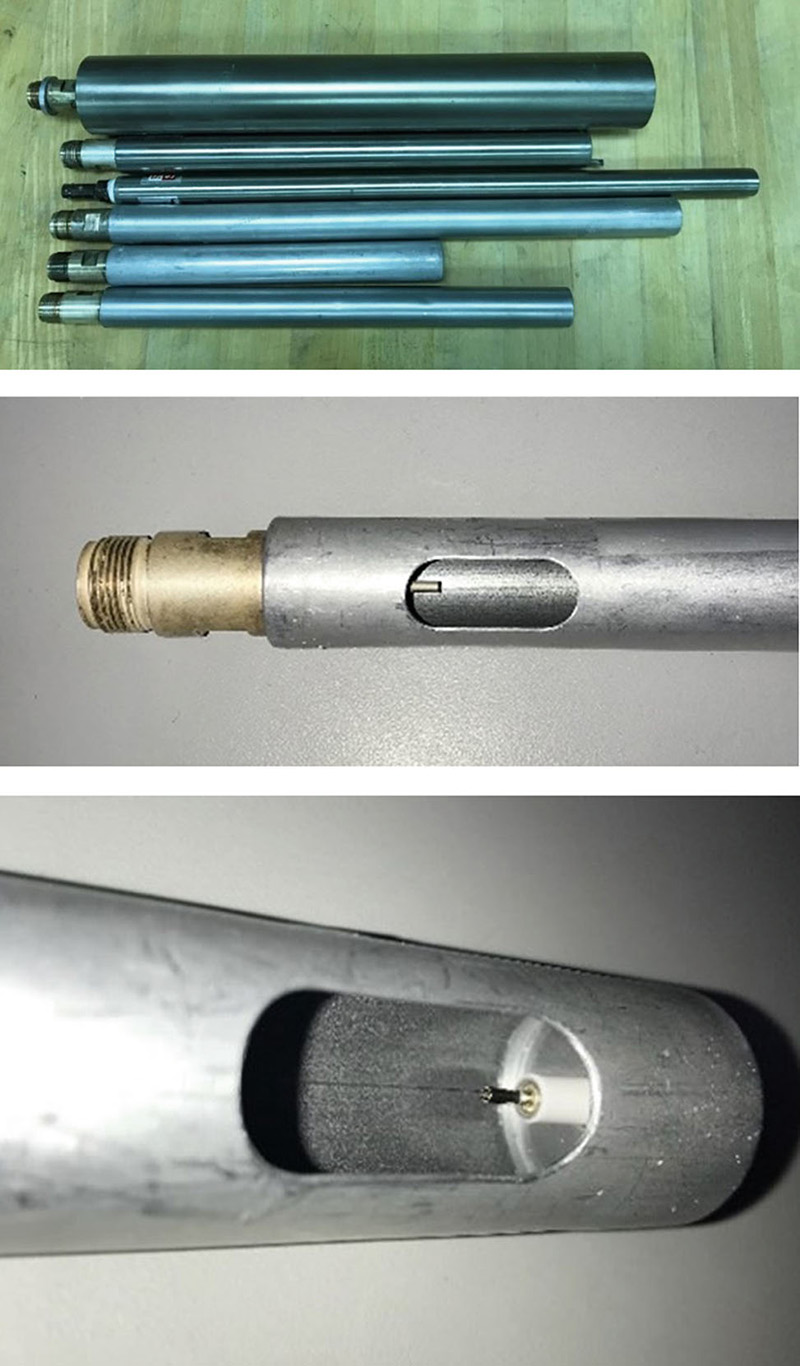

3.1 Helium-3 proportional counters

Helium-3 proportional counters are a very popular way of detecting neutrons as they have a high absorption cross section optimized for thermal neutrons (i.e., neutrons with low energy) and negligible sensitivity to gamma rays. Thermal neutrons are generally preferable for NDA instruments over fast neutrons because of the higher likelihood of thermal neutrons to undergo nuclear reactions. In cases where the source emits fast neutrons, moderating materials such as high-density polyethylene can be used to slow them down and reduce their energy for detection.

In helium-3-gas-filled proportional counters, absorption of a thermal neutron in an (n,p) nuclear reaction creates hydrogen-1 (proton), hydrogen-3 (tritium), and a release of energy (764 keV). The proton and tritium ionize the gas, which is collected and produces a pulse. Each pulse observed is a neutron detected. The time distribution of the pulse streams is then analyzed to determine the number of neutrons, as well as the number of correlated pairs and triples.

3.2 High-level neutron coincidence counter (HLNCC)

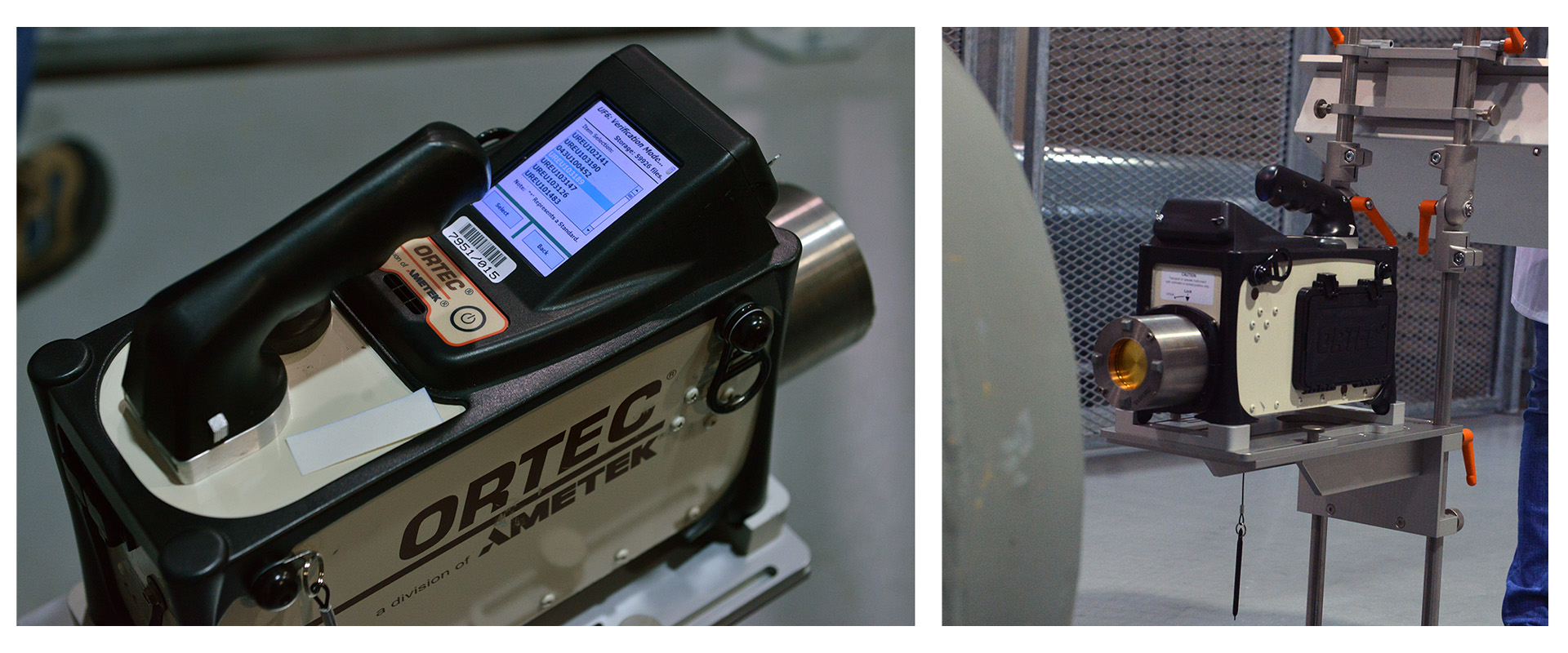

The HLNCC is the standard instrument for assaying plutonium content up to a few kilograms via passive coincidence counting of plutonium-240 spontaneous fission neutrons (Fig. 9). It uses multiple helium-3 tubes positioned around the detection assembly and was originally developed at Los Alamos for the IAEA under the US Support Program to IAEA Safeguards. Examples of the types of materials it can assay include plutonium dioxide, MOX fuels, metal carbides, fuel rods, fast critical assemblies, solutions, scrap, and waste.

3.3 Active well coincidence counter (AWCC)

While the HLNCC is useful for assaying plutonium-240, it is ineffective for uranium-235, whose rate of spontaneous fission is effectively too low to detect using passive neutron techniques. Furthermore, gamma ray spectroscopy has limited use, as it can only measure the exterior of the nuclear material. The solution is to use an active rather than passive approach—applying a neutron source to induce fission and increase neutron production, known generally as an active assay.

The AWCC uses an americium-241/lithium source of uncorrelated neutrons that have energies below the threshold for uranium-238 fission—hence they only induce fission on uranium-235. The mass of uranium-235 is then derived by coincidence counting similar to plutonium. A wide variety of HEU (highly enriched uranium)-containing materials can be assayed, including bulk uranium dioxide, highly enriched uranium metals, and uranium alloy scraps. It can also be used in passive mode, without the neutron source, to detect plutonium-240 and uranium-238 in a manner similar to the HLNCC.

3.4 Uranium neutron coincidence collar (UNCL)

It is essential that nuclear inspectors be able to independently confirm the composition of nuclear materials without relying on statements from the operator. This can be a particular concern when measuring uranium-235 content in fresh LWR fuel assemblies, especially those for pressurized water reactors (PWRs), which contain a variable number of burnable poison rods that can complicate NDA inspections. The poison rods’ function in the assembly is to absorb neutron flux for higher uranium-235 enrichment levels, but they also absorb the thermal neutrons applied in an active assay (such as with the AWCC). As such, inspectors need to know how many neutron-absorbing rods are contained in the assemblies to obtain correct calculations.

To solve this puzzle, Los Alamos researchers—working in collaboration with the IAEA in the late 1970s—invented the uranium neutron coincidence collar (UNCL; see Fig. 10). This instrument uses cadmium liners around the sample cavity to filter thermal neutrons from the applied flux, leaving only fast (high energy) neutrons for the interrogation, which are not absorbed by the poison rods. Although effective, the one drawback to this solution is that because the stimulated fission rate is reduced, measurement times are increased, to around an hour.

3.5 Add-a-source method for correcting errors in waste drums

Waste drums contain complicated mixtures of materials—such as concrete, polyethylene, wood, paper, and metal—that can introduce error into verification measurements by absorbing thermal neutrons and reducing neutron flux energy. Inspectors can, however, correct for this bias using the add-a-source method. This method works by adding an additional neutron source, for example californium-252, positioned at one or more locations around the sample (californium-252 is often used because it produces fission neutrons with a similar energy to nuclear material.). By measuring the change in counting rate from this source specifically (whose stream of neutrons can be separated in analysis using neutron multiplicity counting), the absorption rate of the material can be inferred. This corrective factor can then be applied to the final verification measurements. Add-a-source also requires a calibration, which is typically performed by creating mock waste containers with matrix materials that are expected to be in the assay items.

Summary

The NDA instruments featured in the Los Alamos SSTTP stand out not only for their utility in nuclear safeguards but also for their historical significance and continuing innovation. Many of these instruments—like the high-level neutron coincidence counter and the active well coincidence counter—were first conceptualized and built at Los Alamos and have since become international benchmarks in nuclear measurement.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Bill Geist and Marc Ruch for their assistance in writing this article.