Atomic Management: The DYMAC 2.0 Initiative

- Jake Bartman, Communications specialist

Every day, workers in Los Alamos National Laboratory’s plutonium facility (PF-4) handle significant quantities of nuclear material more valuable than gold. Beyond their expense, these hazardous materials pose substantial security risks, and Los Alamos has stringent legal and ethical obligations to account for all the special nuclear material under its control.

In the past five years, the Laboratory has developed its capacity to produce war reserve plutonium pits for the nation’s stockpile, with the goal—established by the National Nuclear Security Administration—of producing no fewer than 30 pits per year by 2030. Increasingly, however, tracking and accounting for special nuclear material inside PF-4, which for decades was primarily a research and development (R&D) facility, has created a bottleneck: The process of assaying material involves pausing production, removing the material from the production line, transporting it to a centralized laboratory for analysis, and then returning it to production. Because such inventory reconciliations often occur twice per year and take several weeks apiece, they can potentially cause major impacts to production timelines.

In fact, PF-4 was originally designed to avoid exactly this kind of bottleneck. The Dynamic Materials Accountability (DYMAC) system, which went into operation with the facility in 1978, incorporated a suite of nondestructive assay (NDA) tools and other technologies in the glovebox line throughout the facility. The idea—highly ambitious for the time—was to provide a near-real-time account of the movement of special nuclear material through PF-4, ensuring that nuclear material accounting goals were met. However, in the decades after the facility opened, the system degraded. One unsurmountable challenge the system faced was detecting the signature of a given source against the background of a busy and constantly changing operating environment—akin to trying to hear someone speak in a hurricane. The nascent computer technology available in the 1980s was not sufficiently advanced to solve this complex problem.

Although a centralized approach to asset management was sufficient when the facility operated at an R&D scale, this approach could become a critical constraint as activity increases for pit rate production. In 2020, a team of researchers led by Rollin Lakis launched DYMAC 2.0. The initiative is designed to find new methods of dynamically monitoring the movement of material in the facility, fulfilling the promise of the original DYMAC system. As a part of DYMAC 2.0, researchers are building on decades of advances in safeguards R&D to create novel methodologies and tools to implement in PF-4.

The techniques that the DYMAC 2.0 team is developing—which range from incorporating additional radiation shielding around detectors to deploying distributed sensor networks—contribute to the goal of having an accurate, near-real-time account of the movement of material through PF-4. These developments are expected to increase production speed, lower facility downtime, and save millions of dollars, all while reducing workers’ exposure to radiation.

Road to DYMAC: International safeguards

DYMAC 2.0 continues a legacy of nuclear safeguards R&D work that began at Los Alamos nearly six decades ago. In 1966, nuclear physicist Bob Keepin returned to the Laboratory from two years at the International Atomic Energy Association (IAEA) in Vienna, Austria. At the time, IAEA inspectors—who were beginning to monitor nuclear facilities around the world to ensure against the misuse or theft of nuclear materials—relied on inspections and destructive techniques, sending samples of material to laboratories for analysis (see 50th Anniversary of the Safeguards and Security Technology Training Program). Such methods were time-consuming and could disrupt operations while also using up valuable material.

Keepin had the revolutionary idea that Los Alamos could develop technologies to assay nuclear material nondestructively. Soon, scientists at the Laboratory began developing gamma-ray and neutron detectors for safeguards. In addition to reducing the need to divert valuable material for assay, the NDA tools developed at Los Alamos enabled IAEA representatives to assess the materials at nuclear facilities much more quickly—in minutes or hours rather than days or weeks. Within a decade of their development, these tools were being applied in the new DYMAC initiative and slated for use in Los Alamos’s PF-4, which was then being built (see below this article for information about the original DYMAC initiative).

“We have four decades of development that we can apply here at Los Alamos.”

— Robert Weinmann-Smith, Safeguards Science and Technology

PF-4 today: Identifying a bottleneck

Today, however, inventorying material in PF-4 involves a logistically complex process of “bagging out” the material (loading specialized containers for transport) and then moving it to a centralized NDA laboratory for analysis. This process is time-consuming and disrupts production in just the way that the DYMAC system was designed to avoid—and these problems are expected to grow more acute as pit production efforts increase.

Robert Weinmann-Smith, a researcher with DYMAC 2.0, says that the Laboratory’s decades of work in international safeguards are being brought to bear on DYMAC 2.0. “Over the last 40 years, the reason the tools have developed is because of international needs,” Weinmann-Smith says. “Now, we have four decades of development that we can apply here at Los Alamos.”

For example, in the past two decades, researchers at the Laboratory supported the development of safeguards at the Rokkasho Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing Facility in Japan. The Rokkasho facility is designed to separate plutonium from spent reactor fuel so that it can be recycled into mixed oxide (MOX) fuel.

Los Alamos developed an NDA system that made it possible to monitor fluctuations in the Japanese facility, maturing technologies that now underpin the deployment of DYMAC 2.0. Notably, as a part of the Rokkasho project, researchers advanced a Los Alamos computational technique called list mode, which involves recording separate streams of data from individual sensors in fine-grained detail. List mode records detailed information about each detected neutron event as a chronological list, including the timestamp and position.

“Since the original DYMAC system was deployed, electronics have improved enough to enable measurements on a nanosecond timescale,” Weinmann-Smith says. “And so, for example, if an item passes by in the trolly overhead and the background goes up for a few seconds, we can then subtract a little more background for those seconds. We can now do all of this with very high fidelity.”

These advances are enabling the development of new NDA techniques for PF-4. “A detector is a collection of sensors combined together,” Weinmann-Smith says. “In the past, in a measurement, you’d put an item in a detector, you’d hit start, and you’d come back 30 minutes later for your reading. Now, we read the sensors’ measurements independently, which allows us greater spatial and time resolution. That allows us to conduct sophisticated analyses while speeding up the measurements and reducing uncertainty.”

Applying Los Alamos innovations: A dual-pronged approach

List mode may also prove a key technology in addressing the issues with background radiation that plagued the original DYMAC system. As a part of DYMAC 2.0, researchers are evaluating techniques and technologies that span the full spectrum of technology readiness levels. For example, the simplest way to reduce background radiation is to increase the amount of shielding around neutron-emitting materials. However, the fast neutrons produced from plutonium fission are highly penetrating and require large amounts of cumbersome shielding—depending on location, a foot or more of shielding can be needed to absorb stray neutrons from a given source.

Consequently, researchers are also evaluating other, more sophisticated techniques to account for background radiation, broadly divided into two approaches. The first approach involves modifying neutron detectors to include an additional array of sensors that measures the background. These sensors are arranged in the detector as concentric rings—the inner ring measures neutrons from the sample while the outer ring measures background radiation—and, using list mode, measurements of incoming neutrons can be dynamically subtracted from the measurements of a material. This approach is being incorporated into NDA tools such as the dual assay instrument with list mode (DAIL) and the XL Line detector (described later).

“Since the original DYMAC system was deployed, electronics have improved enough to enable measurements on a nanosecond timescale.”

— Robert Weinmann-Smith

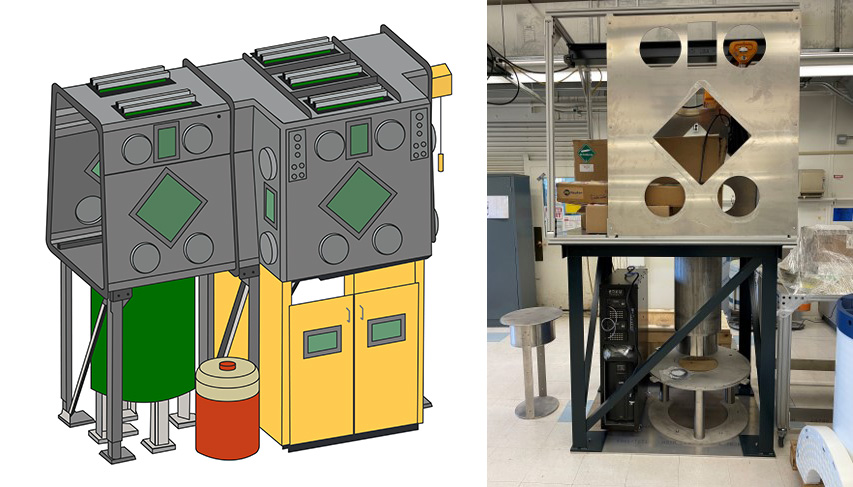

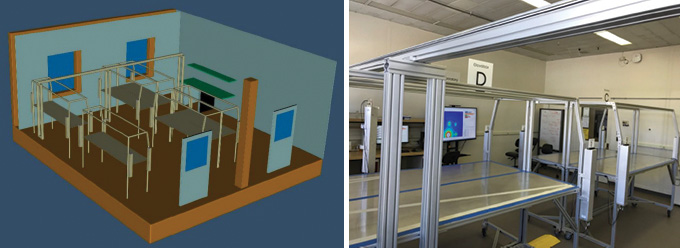

A second approach to addressing background involves deploying a distributed sensor network to monitor neutron flux. To optimize this approach, researchers created a testbed comprising four mock gloveboxes, each with a helium-3 detector in every corner (Fig. 5). This testbed, with its dispersed sensors, allows researchers to evaluate the feasibility of monitoring nuclear material in different configurations inside the glovebox.

“Background is always a signal from somewhere,” Weinmann-Smith says. “That means that if we’re able to measure the plutonium everywhere in the facility, and if we know that, for example, a given glovebox has a hundred grams of plutonium in it, we can calculate how much background that hundred grams is contributing, and we can subtract that background dynamically. We can solve the background everywhere and propagate to where a given measurement instrument is.”

This distributed approach is especially useful in accounting for “holdup”—the residue, dust, or powder that is left over inside gloveboxes as a part of material processing. As a part of inventory reconciliations, workers undertake the laborious task of accounting for this material using NDA tools and statistical methods. Although localized sensor networks are well suited to tracking material during individual steps in the production process, constantly monitoring gloveboxes throughout the facility would make it possible to track holdup as well.

1. Assaying waste with DAIL

When DYMAC 2.0 was created in 2020, the initiative’s goals in PF-4 were threefold: improve the characterization of background radiation, determine where NDA tools could be best applied, and develop a methodology to track items. The team considered tools that were lab ready as well as longer-term approaches, including technologies as diverse as digital twins, radiofrequency identification (see Tracking Nuclear Materials Using RFID), and sophisticated spatial absorption models. Today, researchers are developing several advanced NDA instruments that can be incorporated into PF-4’s production line, including DAIL, which is intended to augment the assay process in PF-4’s 400 wing.

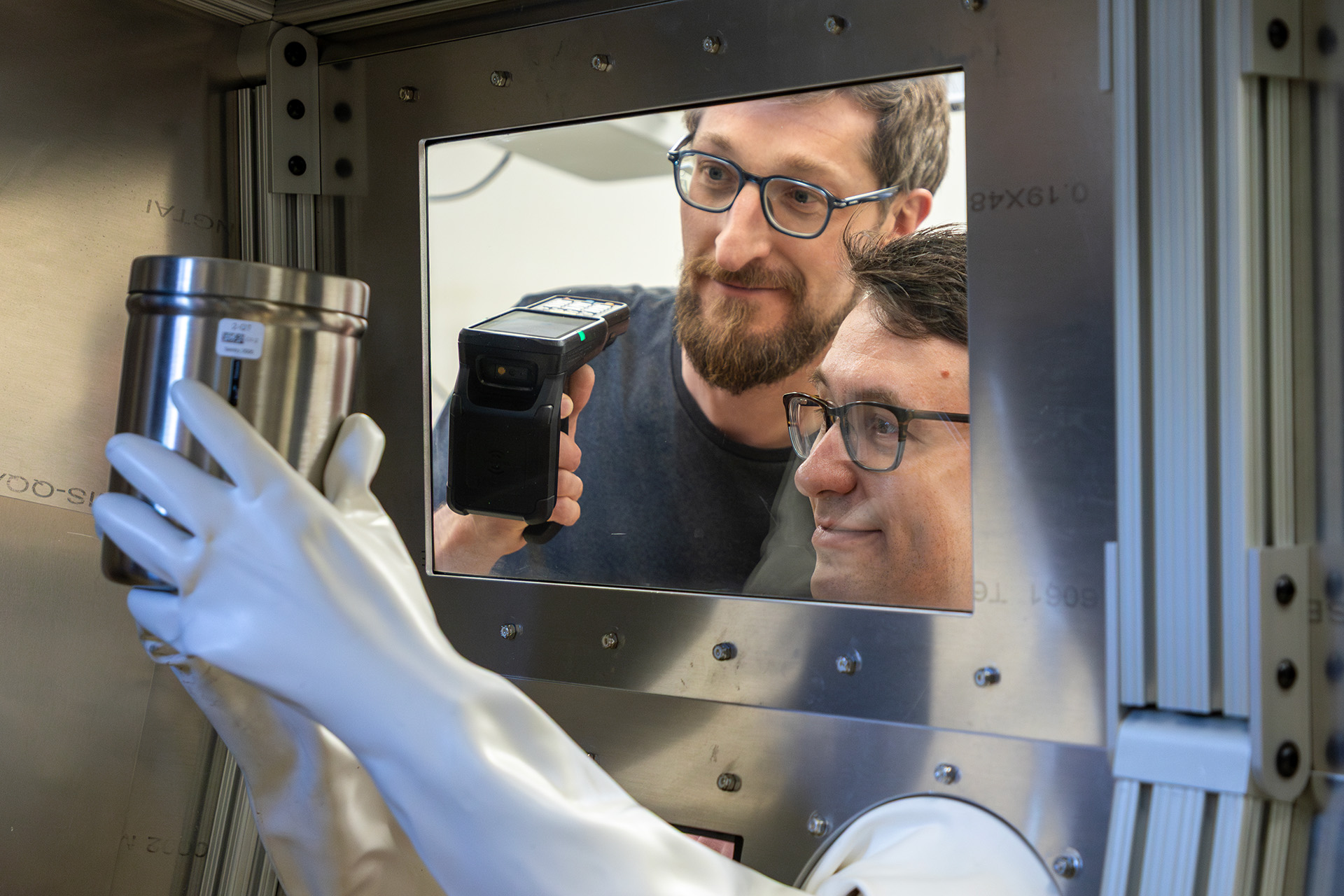

In the 400 wing, transuranic waste is packaged for disposition. Currently, waste in the 400 wing is bagged out into a drum, assayed in PF-4’s NDA laboratory, and measured with a high efficiency neutron counter (HENC; see Fig. 2). Then, it is packed and sent to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in southern New Mexico for long-term storage. This process involves moving waste three times—an inefficient arrangement that increases workers’ risk of exposure to hazardous material. Moreover, the limitations of current measurement techniques are such that the waste containers aren’t packed as fully as they could be.

DAIL, which is a bit larger than a washing machine, is intended to reduce the movement of material and increase efficiency by assaying material in the production line itself, right before it is loaded into 55-gallon waste drums. The instrument consists of a gamma detector and a thermal neutron detector (hence the “dual assay” in its name) in a central cavity that is large enough to accommodate a 5-gallon waste container (Fig. 3). The material could be anywhere in that space, causing measurement uncertainty and requiring the 55-gallon drum in turn to be conservatively filled to less than the legal limit. However, with list mode, the helium-3 neutron sensors can be used to triangulate, with a high degree of precision, the location and volume of material in the 5-gallon container, allowing operators to determine (for example) if the waste is evenly spread out or concentrated near the bottom of the container, where its neutron flux could be problematic.

“The location of material inside the container is the single biggest source of uncertainty for this kind of measurement,” Weinmann-Smith says. “Our studies show that this design allows us to cut down on uncertainty by 75%.”

DAIL incorporates an outer ring of sensors that take background radiation into account, as described previously. This crucial innovation—which was matured at DYMAC’s testbed—allows for assay to be conducted in the production line, while ensuring that sudden changes in background don’t hamper the detector’s measurements. To develop DAIL, researchers drew on several earlier detectors such as HENC and ENMC (epithermal neutron multiplicity counter).

In fiscal year 2023, Los Alamos sent 817 drums of transuranic waste to WIPP, each costing hundreds of thousands of dollars to process. If DAIL was incorporated into the 400 wing, the instrument could make it feasible to pack 20 to 40% more material in each drum than is possible with current methods—a significant reduction in the number of drums sent. In addition to saving millions of dollars, DAIL could speed up the characterization process by around 20%—saving some 36 days per drum—all while reducing workers’ potential exposure to hazardous material. The detector is expected to enter operation by the end of 2026.

2. Aqueous chloride processing: The XL Line detector

Another project inaugurated under DYMAC 2.0 is an NDA instrument for PF-4’s XL Line. At this processing line, plutonium and americium are extracted from materials including legacy waste—primarily salt residues that were used decades ago in research—and the tail, or waste, from another separation process (see Actinide Research Quarterly First Quarter 2023 for more information). In effect, it is a salvaging operation for valuable radiological elements. Part of processing requires quantifying extracted plutonium to keep track of it, and like other analytical processes in PF-4, this is a tedious process that involves bagging out and transporting material to the centralized NDA laboratory.

An in-line thermal neutron counter would bolster worker safety and substantially improve the XL Line’s efficiency, says Nick Smith, who leads the XL Line detector’s development. “Any time you can introduce an in-line detector, you can substantially reduce the time you need to make a measurement, you reduce effort, and you increase safety,” Smith says. “And, really, safety is the biggest thing here. Whenever you have to bag out material, you have the risk of an accidental release. We can eliminate that risk with an in-line detector.” Lakis adds that the decrease in time and effort associated with in-line measurements will substantially increase efficiency for the pit production mission, too.

The minifridge-sized instrument is based on DAIL, with a similar neutron detecting well that employs dynamic background subtraction techniques and list mode. There are, however, some unique challenges for the XL Line detector. The processed actinide salt solutions vary greatly in composition, complicating efforts to meet the required precision and accuracy standards. Moreover, unlike DAIL, which was designed to integrate with a newly constructed glovebox, the XL Line detector must be retrofitted onto an existing one.

“Like a custom car, there are aspects of these detectors that you just don't change.”

— Nick Smith, Safeguards Science and Technology

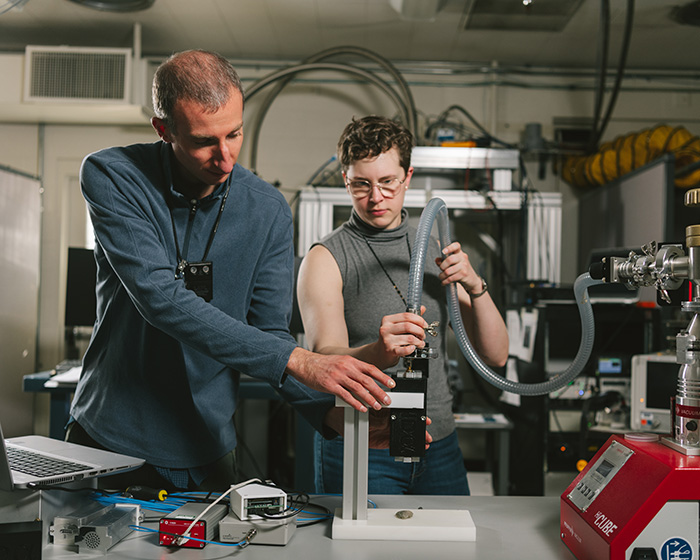

Rachel Connick, who recently converted from a postdoctoral to staff position, has been working to help design the XL Line detector. Connick says that, among other difficulties, developing a detector small enough to fit beneath an existing glovebox complicates the design because a shorter detector means shorter helium-3 tubes, reducing efficiency. Connick’s work has also involved implementing a custom gamma detector into the detector’s design. In addition to difficulties related to space constraints, incorporating a gamma detector into the bottom of the neutron detector’s well affects the behavior of neutrons inside the well, adding complexities that must be accounted for to ensure that the detector meets requirements.

Smith, who expects the detector to be deployed within the next four years, likens the development to the process of designing a custom hot-rod car. Although all cars have certain characteristics in common—four wheels, an engine, and a transmission, for example—cars vary widely depending on what kind of driving the car is intended for (a drag race or the Indy 500).

Similarly, although different NDA tools have characteristics in common, each tool must be designed to suit a specific application.

“Like a custom car, there are aspects of these detectors that you just don’t change,” Smith says. “Different detectors may be similar in principle. But they’re very different in practice.” Lakis observes that this is the “art and practice of detector engineering— balancing the design and performance, within constraints, to best accommodate the mission.”

3. DBCM: Continuous background monitoring for plutonium in PF-4

Connick and Weinmann-Smith are both contributing to another DYMAC 2.0 project, the DYMAC background characterization module (DBCM). This portable system comprises eight neutron detectors on flagpole stands and a cart bearing data acquisition electronics (Fig. 6). It can be positioned around a glovebox to monitor the production processes inside, allowing for tracking and accountancy of plutonium and other special nuclear materials (Fig. 7).

DBCM was designed to evaluate the signals and background that a network of sensors might pick up inside PF-4. A fully developed version of the system could resemble the glovebox unattended assay and monitoring system (GUAM), which was developed at Los Alamos for implementation in Japan Nuclear Fuel Ltd.’s J-MOX facility (slated to enter operation in 2028). GUAM uses a sensor on every glovebox, passively measuring plutonium levels overnight and providing data to operators every morning about the plutonium’s quantity and location. A similar scheme, the plutonium inventory measurement system, was created for the Rokkasho facility.

Recently, DBCM detectors were deployed at a process (or room) inside PF-4, with the goal of capturing neutron data and continuously tracking nuclear material inside the glovebox. However, during this test, the neutron detectors proved sensitive enough to pick up neutrons emitted from plutonium-238 processing in an adjacent room. This background signal overwhelmed the detectors, preventing measurement of the primary source material—not the outcome that the DYMAC 2.0 team had expected. The result highlighted the need for detectors spread out through the entire facility. But background is always a signal from somewhere, and the team directly mapped the background fluctuations to processing plutonium-238.

“We could see to the minute when different processing steps started, and on the weekend or at night, the signal was dead flat,” Weinmann-Smith says. “In the future, we’d want to track everything happening in each of the room’s gloveboxes on a minute-by-minute basis.”

Researchers hope to put DBCM in another room of PF-4 this year, demonstrating proof of concept before deploying it facility-wide. Although there are significant engineering challenges to pioneering such a system in a busy work environment like PF-4, doing so could almost eliminate operational pauses for nuclear material control and accountability.

Looking to the future

Today, Laboratory researchers are leveraging decades of experience in safeguards research to overcome the challenges that led to the original DYMAC system’s dissolution. The tools and techniques that are in development as a part of DYMAC 2.0 represent a broad-based approach to solving enduring challenges in nuclear material accounting. Some of these developments, such as DAIL, are nearer to implementation; others, such as DBCM, need additional research to be developed into mature systems. Taken together, these methods point toward a future in which nuclear material accounting at Los Alamos is faster and more effective, supporting production and bolstering safety throughout PF-4 for decades to come.

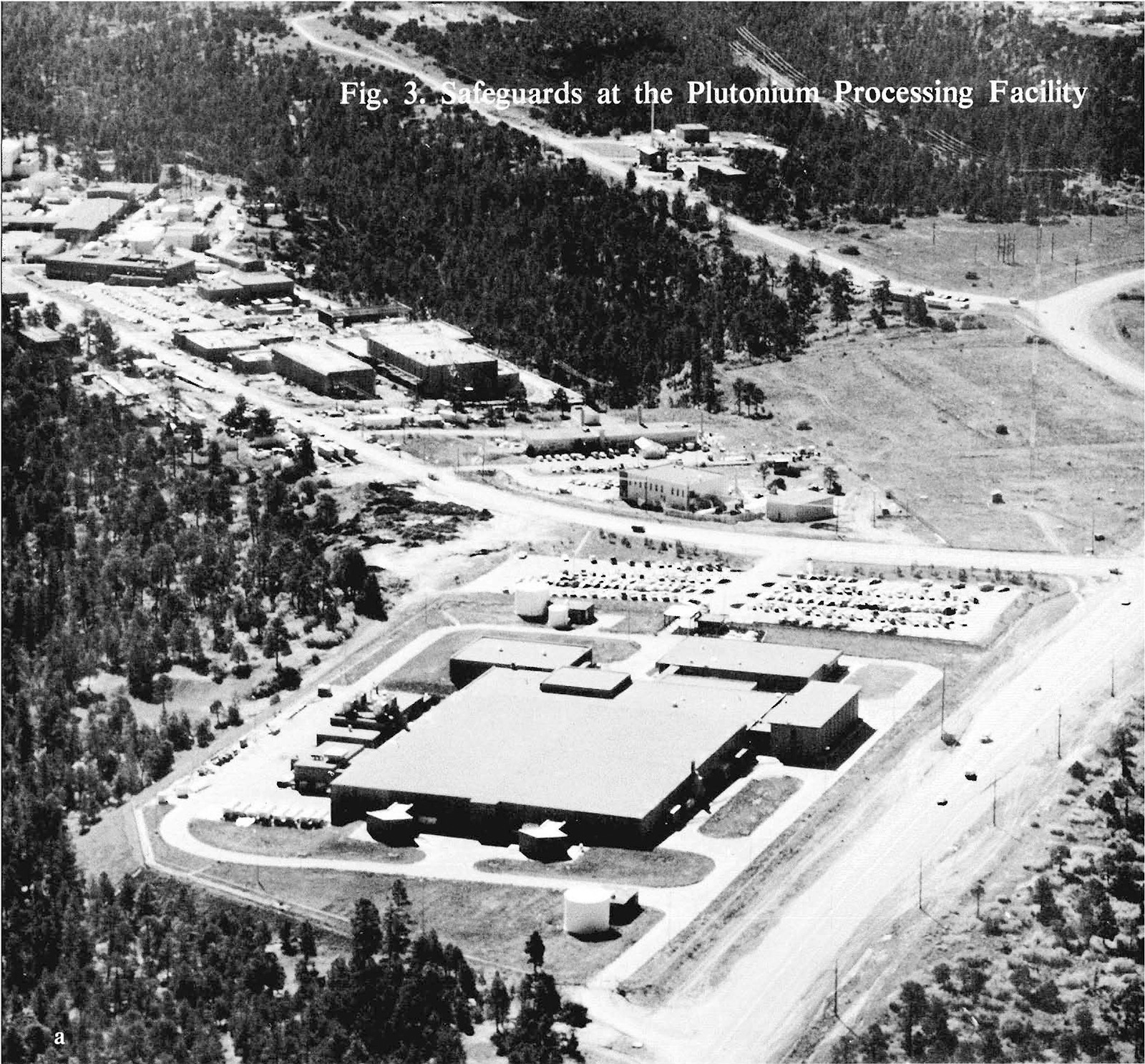

A Look at the Past: DYMAC 1.0

In the mid-1970s, Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory (as the Laboratory was then known) was developing plans for PF-4—a high-tech facility that would research and process plutonium. Researchers in Los Alamos’ safeguards program understood the importance of accounting for special nuclear material inside the new facility, and they proposed implementing what they called the Dynamic Materials Accountability (DYMAC) system in PF-4. DYMAC would combine video cameras and NDA tools with computer technology to keep an accurate and near-real-time account of all the nuclear material inside the facility. By taking advantage of the latest computing developments and NDA techniques, it would be possible to develop a system that would measure nuclear material during processing.

DYMAC entered operation when PF-4 received its first shipment of special nuclear material in January 1978. Four years later, in 1982, a group of researchers published a report that evaluated the DYMAC system. The report noted that the system was a significant improvement over pre-DYMAC methodologies. Prior to DYMAC, “accountability of nuclear material lagged weeks behind the constantly changing physical inventory” because the methods involved relying on process personnel to write paper transactions on a timely basis. With its incorporation into the production line itself, DYMAC reduced the need for these post-hoc inventories. However, the report noted that DYMAC’s implementation remained imperfect and that the system was accomplishing around 75% of its design goals, largely because it lacked certain key tools for analyzing the collected data.

In subsequent decades, the DYMAC system deteriorated. For one thing, the system was ill-designed to handle new workflows in PF-4, which introduced new kinds of special nuclear material—and higher volumes of material—into the facility. These changes created challenging levels of background radiation that hampered the system’s accuracy, and over time, the system of dynamic material monitoring that Bob Keepin and others had envisioned went by the wayside.