From Trash to 100-Tesla Treasure

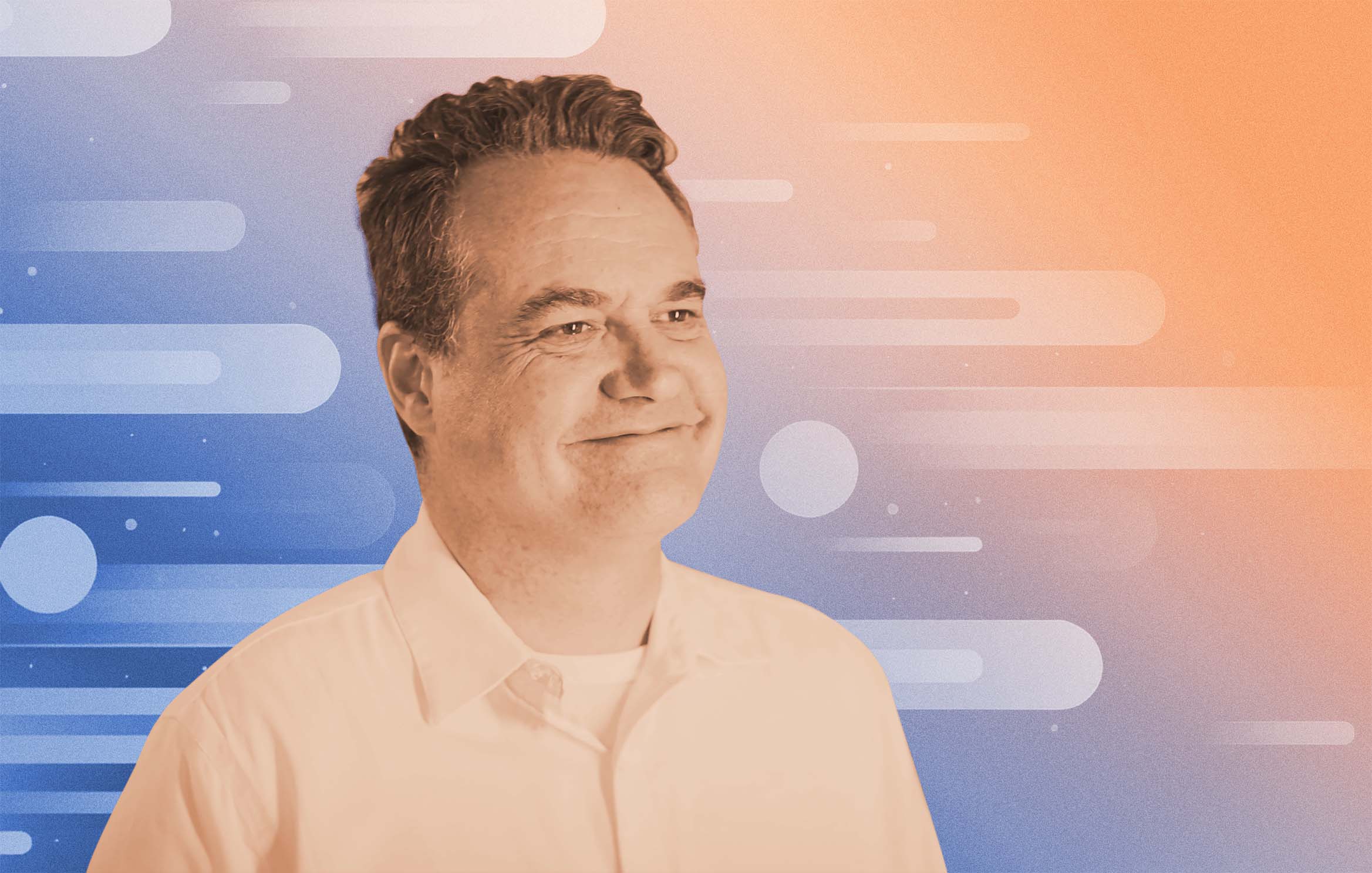

The Pulsed-Field Facility draws scientists from around the world to Los Alamos.

- Eleanor Hutterer, Editor

Inside a strange building with five‑foot-thick concrete walls and six‑foot-diameter portholes resides a family of magnets unlike any others in the world. This is the Pulsed-Field Facility (PFF) at Los Alamos, a paragon of ingenuity and one of three facilities that comprise the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, (the Magnet Lab). The building itself was inherited from another project, hence the anachronistic portholes. So too was the enormous motor-generator that powers the magnets from the more conventional building next door. This generator, once dormant and destined to be scrapped, is what makes the record-setting magnetic fields at this world-class research facility possible, though it was never intended for this purpose.

In the mid-1980s scientists at Los Alamos were planning a new facility, the Confinement Physics Research Facility, to study nuclear fusion. The project required strong magnetic fields, which in turn required a very large power source for the intended electromagnets. Unlike permanent magnets, electromagnets are transient and are only magnetic when powered by electricity. After scouring the country, the scientists happened upon a giant sleeping in a Tennessee field, near the banks of the Cumberland River.

The behemoth lay in pieces inside a warehouse, its life seemingly over before it had begun. The nearly 700-ton Swiss-made steam turbine generator was one of several that had been purchased new a decade earlier by the Tennessee Valley Authority for the planned, and then abruptly canceled, Hartsville Nuclear Plant. Never even assembled, it was sold to Los Alamos for little more than the price of scrap.

The 1200-mile journey west began in 1987 and required numerous feats of engineering, as the generator, weighing about the same as four large blue whales, was the heaviest single load ever to travel on New Mexico roads. First, the stator and the rotor, the two largest pieces of the generator, were repacked into their original crates and loaded onto a barge, which traveled down the Cumberland River to the Ohio River, then by way of the Mississippi River to the Arkansas River and into Catoosa, Oklahoma. Next, the crates were loaded onto special train cars custom built for the second leg of the voyage, a convoluted rail route dictated by bridge weight restrictions, to Lamy, New Mexico. Finally, in the spring of 1988, the generator completed its journey with much fanfare, traversing the 65 miles from Lamy to Los Alamos by road, in a slow-moving convoy that drew crowds, closed roads, and used special temporary bridges and load spreaders for the 17 bridge and culvert crossings along the way.

Bizarrely, no sooner was the enormous generator finally installed in its brand new building, than the plasma confinement project, like the nuclear power plant, was abruptly canceled. It was late 1990 and the rotor had been turning for one week.

Meanwhile, elsewhere on the Hill, discussions were under way about Los Alamos joining a National Science Foundation collaboration, as the site of a new pulsed-field facility for the Magnet Lab. One aim of this proposal was to build the first long-pulse 60-tesla magnet. (A tesla is a large unit of magnetic field strength; even a hospital MRI usually operates at only 3 tesla). Among the Laboratory’s assets were an essentially new generator, recently orphaned and ready to power the proposed 60-tesla magnet, and a robust body of expertise in explosives-generated high magnetic fields and capacitor banks. And so, Los Alamos was chosen as the home of the PFF.

This time the project didn’t fold, and over the past 28 years the generator has powered the PFF to new limits and world records. In 1997 the facility achieved the original goal of generating the first 60-tesla pulse to last longer than 100 milliseconds. And in 2012, facility scientists set a world record for the highest non-destructive magnetic field with their “100-tesla shot,” a heart-stopping moment during which the facility’s largest magnet surpassed 100 tesla for a thousandth of a second. That magnet, the crown jewel of the facility’s user program, now routinely provides 95 tesla for scientists from around the world.

The machine behind the magnets alternates between motor and generator. First it’s a motor, spooling up to store electrical energy from the grid. Then it’s switched into generator mode and dumps this energy as a short but incredibly powerful burst—the generator itself is capable of a staggering 1.4 gigawatts—into the waiting electromagnets. All that power can raise a large magnet’s temperature from –200°C to room temperature in a second or two. Between the heat from the current and the force from the magnetic field itself, these extreme electromagnets can only be used in quick pulses, lest they melt or blow themselves to bits.

The PFF boasts the most reproducible high-field magnets in the world. Scientists studying the physical properties of metals or superconductors, for example, need many pulses to really learn anything useful. A tiny sample of the material of interest is placed in the bore of the magnet, the magnet is turned on, measurements are made, the magnet is turned off, and the whole thing is reset to go again. On any given day, multiple teams of scientists from around the world may be running experiments; during the 100-tesla shot, experiments on eight different materials were performed simultaneously.

The PFF at Los Alamos embodies a coalescence of capabilities: very high magnetic fields, unique magnet designs and pulse shapes, exquisite temperature control, and innovative probes and measurement technologies. These capabilities, in concert, keep the facility at the forefront of the institutional, national, and global materials-research communities.

Sometimes it takes the very large—like a football-field-sized facility—to understand the very small—like the subatomic properties of semiconductors. And sometimes it takes three tries for a gigantic generator to find its fate.