Shake, rattle, and roll

Engineers put nuclear weapons and their components to the test.

- Jill Gibson, Communications specialist

It’s not easy to be a nuclear weapon. Consider what the approximately 3,500 weapons in the U.S. nuclear stockpile potentially could go through during their lifespans. Put yourself in their shoes… or rather… in their missile silos.

First and foremost, nuclear weapons must always be ready to perform perfectly. They have to be safe, secure, and reliable; never detonating accidentally but always ready to do their jobs, serving as the country’s nuclear deterrent and maintaining America’s ability to hold an adversary at risk. While the goal of deterrence is never to use nuclear weapons, the nation’s nuclear weapons must remain in working order, which means enduring the often extreme conditions of transport (bumpy roads, hot storage containers) and flight (dramatic shifts in temperature, harsh vibrations, intense gravitational forces, radiation, explosions, pressure, and shock).

The weapons in the U.S. nuclear stockpile also must maintain their ability to function flawlessly well beyond their originally intended lifespans. Most weapons in the current stockpile were produced during the 1970s and 1980s. Perhaps you were produced… that is, born… 40 or more years ago. As an aging human, you go to the doctor for regular medical checkups. Modern doctors have developed many ways to extend people’s lifespans and increase their quality of life.

Just like humans who get checkups, weapons (or often just their components) receive tests to determine how they will function in the different environments and situations they might encounter during their lives. These tests play multiple roles. Some tests provide performance data early in a weapon’s design and development process. Other tests determine whether a weapon is ready to return to the stockpile after an update—rather like your doctor checking to see if you are ready to return to work after a surgery. “The goal of testing is to understand how these systems will behave in the real world,” says Evan Ferguson, an engineer at Los Alamos National Laboratory, which is responsible for four of the seven types of weapons in the nuclear stockpile. “We want these tests to be representative of a weapon’s actual experience. That’s our driving force.”

Jay Carnes, acting chief operating officer for Weapons Engineering at Los Alamos, has worked as an engineer and manager for more than 40 years. “Our work involves physical design, materials selection, understanding how things age and change, and examining future engineering problems,” Carnes says. “Weapons can change over time from when they were first fielded. They are sitting in storage going from 80 degrees to 30 degrees Fahrenheit. Our systems are extremely complex. Everything inside a weapon impacts everything else.”

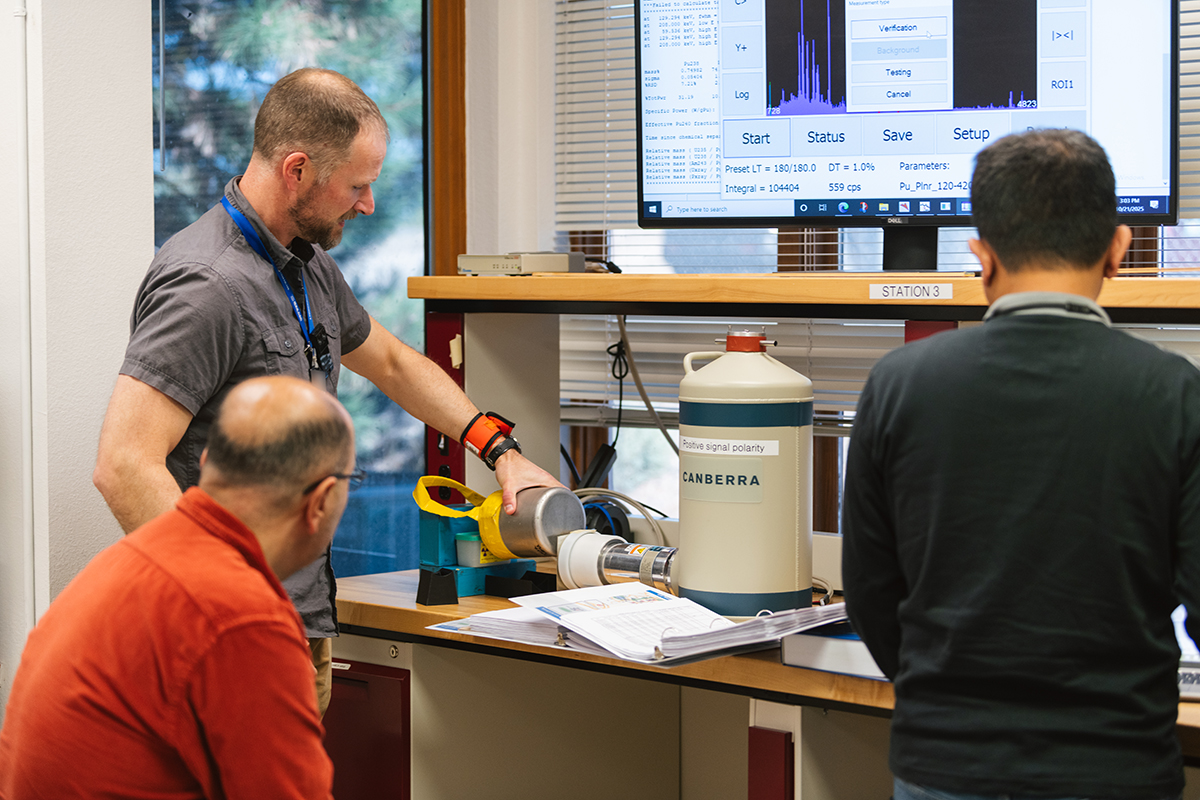

Environmental testing plays a key role in qualification—demonstrating that the weapon, components, or subsystems meet all required design specifications, environmental tolerances, safety standards, and performance expectations under anticipated conditions of use. The tests are non-nuclear, meaning that actual weapons systems and components are tested, but there is no special nuclear material (fissile material that can sustain a nuclear chain reaction) involved. Engineers often substitute mock versions of the nuclear parts of the weapon to ensure the systems match their ‘real-life’ equivalents.

The tests provide information about how weapons and components will function both in expected, or normal, conditions (like storage, transportation, and launch); unexpected, or abnormal, conditions (like accidents such as drops or fires); and hostile conditions (like an adversary attack). Engineers also study how weapons and components perform in combined environments where they may experience several stressors simultaneously. Data from the tests is used for computer simulations and engineering analyses, which in turn inform future tests.

“Testing is integral to engineering,” Carnes says, noting that environmental testing of weapons and components is a crucial part of the Lab’s mission. Los Alamos has several facilities and a variety of equipment that engineers use to put weapons to the test.

Shake it up

What can cause stress to a nuclear weapon? Stress can come from day-to-day operations like being transported from place to place. “Riding across the country on a truck causes vibrations,” Ferguson says. “We need to make sure those vibrations don’t lead to any changes like cracks or deformations.”

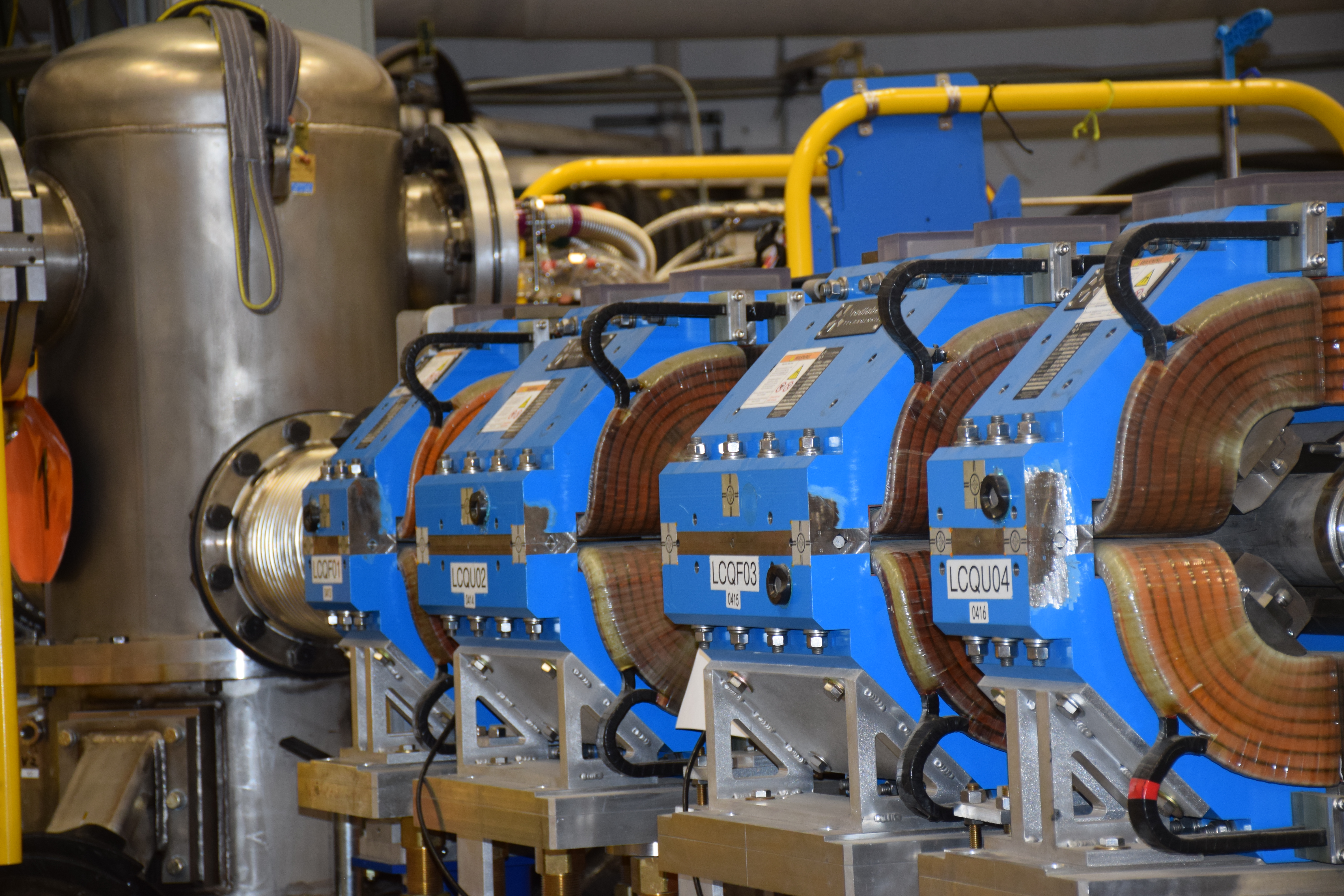

To test this, the Lab uses several electrodynamic shaker systems, commonly known as shaker tables, that simulate the kind of vibrations that weapons and components could encounter in various situations—from transportation to a missile launch. Engineers secure the piece being tested to the table, a large platform that shakes side to side, front to back, or up and down, with 20,000 to 50,000 pounds of force. “We commonly have over 100 channels of data acquisition hooked to the weapon while it’s on the shaker,” Ferguson says. “This allows us to characterize the system’s response from a dynamic standpoint.”

Weapons and components can spend more than 20 hours at a time on the shaker tables with engineers monitoring the process in person. “Our test environments simulate the cumulative vibration stresses a system would endure over thousands of operations hours.,” Ferguson says. “The shaker works like the speaker you have in your car. An amplifier pushes the signal to a massive scale—you can play music through it.”

Undergoing vibration tests helps qualify a weapon to enter the stockpile. “These shakers are booked for the next two years,” Ferguson says. “They’re really in demand.”

Feel the heat

Another potentially stressful situation for a weapon could be extreme temperatures and rapid temperature changes. Simply waiting “on alert” at a military base as the seasons cycle from winter to summer could have an impact. So could sitting on scorching tarmac at an airport during the hottest months of the year.

“A B61 (a Los Alamos–designed and –maintained gravity bomb) will be at its hottest when it’s hanging off a fighter jet on a runway,” engineer Alex Malliett says. “Then the jet soars into the atmosphere, taking that weapon to −40 degrees Celsius. We must make sure it doesn’t experience thermal shock.” That’s why the Lab uses Thermotrons, large thermal chambers that subject weapons and components to extreme heat and cold. Some of the chambers can create rapid temperature changes. Other chambers can maintain high or low temperatures for long periods of time. “Some of our tests last two years,” Malliett says. “This allows us to study how different materials that make up the weapons react to each other during long-term exposure to heat or cold.”

Malliett says he aims to push the limits of what the weapons might experience. “Even if a weapon may only see these conditions one time, or possibly never, we want to have tested it. We want margins for extremes.”

What goes up

Establishing margins is also important when it comes to abnormal environments, which include accidents such as the unlikely possibility that a weapon falls off a truck. One of the Lab’s test devices is a 25-foot indoor drop tower that can speed an object from top to bottom faster than gravity. This simulates a drop farther than the actual 25 feet.

Engineers capture data from the drop tests using accelerometers and other diagnostics. “We use the tower to evaluate safety, assess impact performance, and verify that the components meet required specifications,” Ferguson says.

Take it for a spin

Another environment that weapons engineers must plan for is what a weapon goes through when launching out of or re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere. Engineers use a large centrifuge to recreate gravitational force caused by high levels of acceleration. The weapon or component is attached to the arm of the centrifuge and spun at high velocities around a central axis.

“We use the centrifuge to look at how hundreds of Gs could impact components,” engineer Charlie Tappan says. “Each test takes about a minute, but there are many technical procedures and specifications we must follow due to the potential hazards and the high amount of energy used.” Tappan notes that the centrifuge runs on electricity and uses a vast amount of power. “All the lights in the facility dim when we run it,” he says.

Have a blast

Los Alamos engineers also ensure that weapons can withstand shockwaves. These sudden—and massive—changes in pressure, temperature, and density could result from something like an adversary-triggered detonation. To replicate such conditions, Los Alamos engineers use a blast tube that simulates how weapons or components react to such hostile environments. The 150-foot tube is 8 feet in diameter, large enough for an average sized person to stand up inside, and made of 2-inch thick steel. At the end of the tube, the test object hangs from cables; when released, the object is in free fall, simulating the experience of being in flight when the shockwave hits. The blast itself is created using hundreds of pounds of explosives. When the shockwave hits the test object, it propels the weapon or component forward into a padded catch pit.

“We use two high-speed cameras to capture 3D strain maps (representations of how objects or materials change shape) during the experiment,” Tappan says. He adds that they are redesigning the blast tube to sustain higher forces for increased qualification requirements.

Twist and shout

Measuring strain, torque, and load are the goals of another testing facility, where engineers use a variety of machines (some nicknamed after monster trucks) to carry out tests. “Here we are applying dynamic loads," Malliett explains, gesturing to a machine called a servohydraulic load frame, which uses fluid pressure and precise control systems to apply forces that stretch, compress, and bend parts. “High-speed digital cameras capture images that strain is correlated from,” Malliett says, pointing out how applying a speckled pattern of paint to parts allows engineers to track movement and deformation.

Another device, called a Rapid Angular Acceleration Test Stand (RAATS) exposes parts to rotational acceleration to see what happens when they spin rapidly. Across the room, pneumatic actuators simulate what happens during a re-entry body kickoff, such as when a warhead separates from the missile and begins re-entry into the atmosphere. Nearby, a test rig called the Products of Inertia Machine measures how unbalanced or asymmetrical a component is with respect to rotation, which is important for understanding the impacts of components on flight properties.“We twist, turn, move, and pull parts, condensing what a weapon or part might experience in a lifetime into hours or days,” Malliett says. “We try to identify problems and figure out the best ways to solve them.”

A lifetime of testing

Environmental testing takes place throughout a weapon’s lifetime. In fact, testing begins before design decisions are even finalized. Recently, Malliett has been testing several potential parts for the W93, a new U.S. nuclear warhead the Lab is designing for submarine-launched ballistic missiles. Although the W93 is still in development, it is already going through tests. “We need to make sure we can design individual components that will work,” Malliett says, explaining that it’s important to catch potential problems early in the design process.

Finding failures early heads off future issues, Malliett says, adding, “We get paid to break stuff. We are all about destroying things.”

But testing goes far beyond the initial design phase. The W93 components that make it into the final warhead will be tested routinely throughout their time in the stockpile through a surveillance program and whenever any updates or changes are made.

During their lifespans, any weapon could undergo updates called alterations, modifications, and life extension programs. These updates can involve switching out certain parts for newer or different ones or changing a weapon’s capabilities to meet new military needs. Any significant changes mean it’s time to retest.

After environmental testing, the next step is flight testing. Los Alamos National Laboratory works with commercial rocket companies to conduct “smaller” suborbital launches that test components and prototypes; “larger,” military-conducted flight tests (called Joint Test Assemblies) put mock-weapons and delivery systems through the experience of a real full-scale launch.

“Testing is part of assessing our systems to ensure they are safe, secure, reliable, and will perform,” says Anita Carrasco Griego, acting associate Laboratory director for Weapons Engineering. She also points out that assessing weapons isn’t a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach. Los Alamos is responsible for four of the seven nuclear weapons systems in the nuclear stockpile, and she says each system is unique. “It’s like a parent with children; each one is different. They experience different things as they go through life; they have different environments that they are exposed to. We have to be aware of that and sensitive to the unique characteristics and experiences each system has.”

Carrasco Griego says that means certain weapons may require more or different types of testing. “The weapons are unique for a reason and that means they need to be treated a little bit differently, each one. If one’s going through a hard life, we need to look a little harder and pay attention a little bit more.”

Ferguson, Tappan, Malliett, and the many other Los Alamos engineers who carry out environmental testing understand how hard it is to be a nuclear weapon. “Our aim is to achieve the purest representation of what the weapons, components, and systems might go through,” Ferguson says. “These tests help ensure that America’s nuclear deterrent is ready for whatever it may face.” ★