Desert diagnostics

For more than four decades, Tom Sandoval has supported nuclear weapons and nonproliferation experiments at the Nevada National Security Sites.

- Whitney Spivey, Editor

Growing up in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Tom Sandoval was only vaguely aware of the mysterious town of Los Alamos, about 35 miles northwest. “I had relatives who’d been guards there,” he says. Home to Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, the entire community of Los Alamos was closed to the public from 1943 to 1957. All residents and visitors entered and exited through security checkpoints.

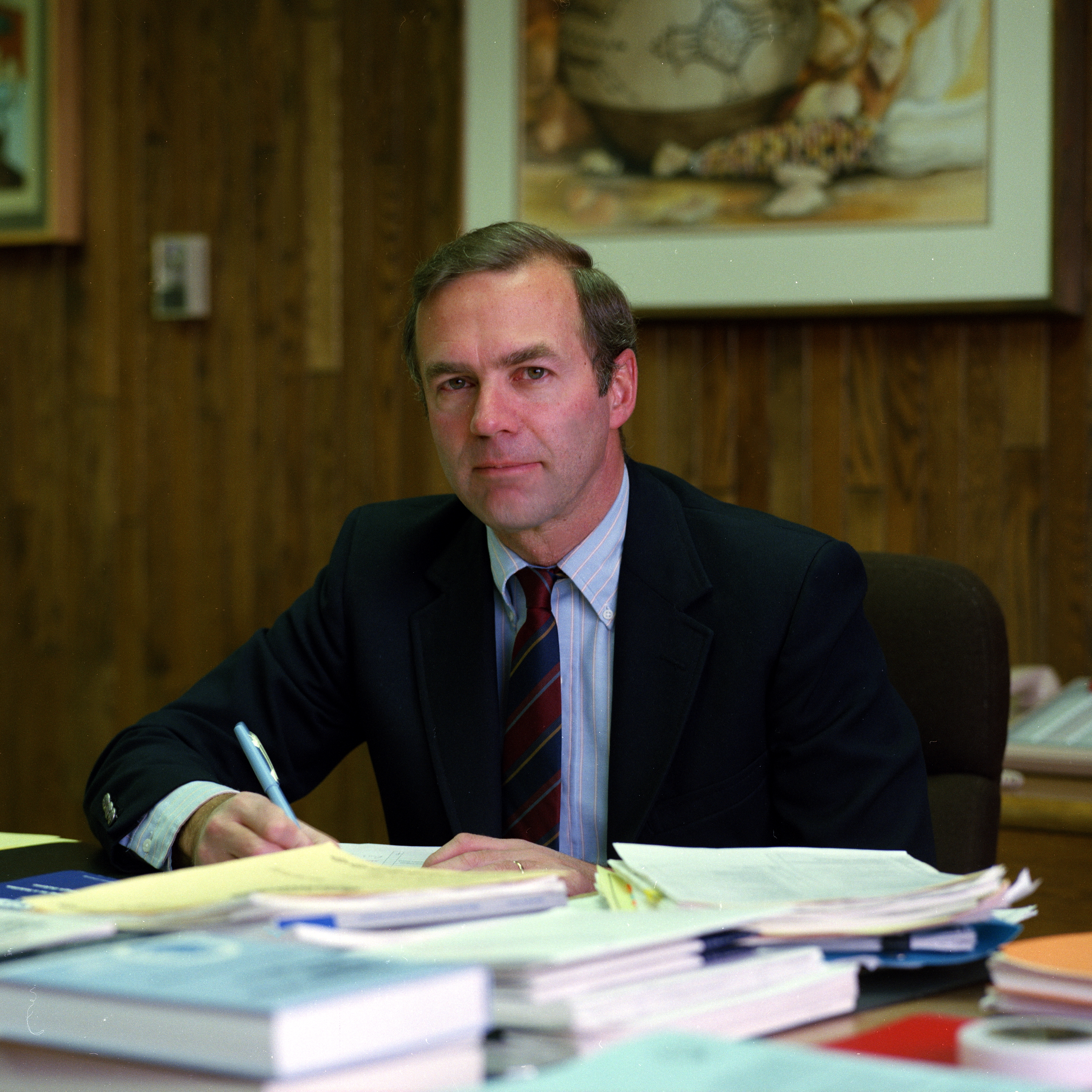

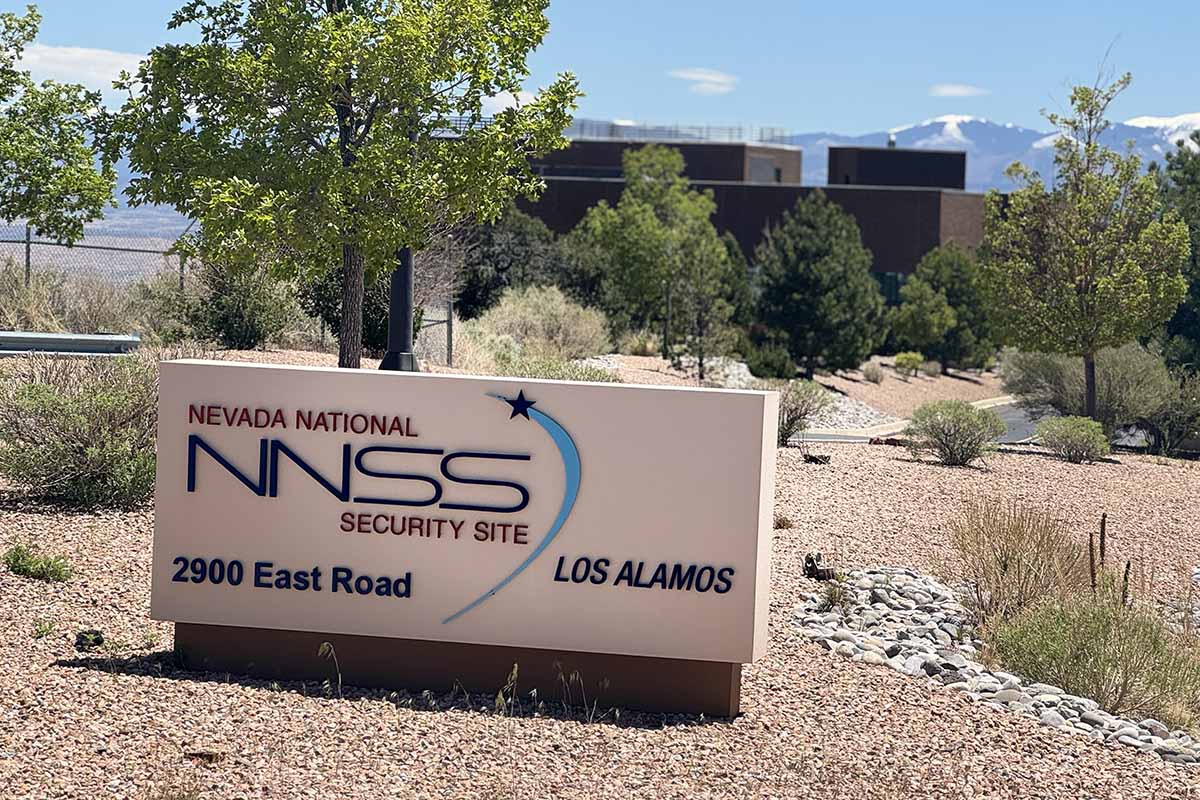

By 1983, however, Los Alamos had long been open to the public, the Lab had been renamed Los Alamos National Laboratory, and Sandoval—newly married and recently out of the Air Force—was looking for work. A family friend encouraged him to apply for a technician position with EG&G, the company that operated the Nevada Test Site (now the Nevada National Security Sites, or NNSS), just north of Las Vegas. Sandoval landed the job, which was based at EG&G’s Los Alamos office, and in early 1984, he began assembling circuit boards and working with fast-framing and streak cameras to record data from underground nuclear tests designed by Los Alamos and conducted at the test site.

The testing days

Sandoval traveled to the test site for the first time in late 1984 and rented a bed in a dormitory for 50 cents a night. He recalls the energy of Mercury, a hub of activity located just inside the site’s southern border. “Mercury had a pool, a bowling alley, and a steak house,” he says. “The test site was rocking back then.”

All that activity was in support of nuclear testing. In the throes of the Cold War, the United States was rapidly developing its nuclear arsenal, and one of the ways that the country’s weapons labs—Los Alamos and Lawrence Livermore—fine-tuned their weapons designs was through nuclear testing. Initially, these tests happened aboveground (mostly at the Nevada Test Site or over the Pacific Ocean), but when the Limited Test Ban Treaty was signed in 1963, testing moved underground, primarily at the Nevada Test Site. The first test that Sandoval supported was Correo, which was detonated on August 2, 1984.

An underground nuclear test began aboveground—with the construction of a towering “rack,” roughly four stories tall. This rack held both the nuclear device and an array of diagnostic instruments designed to capture data from the detonation. Sandoval spent his days climbing the rack’s stairs, installing diagnostics. “I was a lot skinnier back then,” he jokes.

Once ready, the rack was lowered into a vertical shaft up to 3,000 feet deep. The hole was then “contained”—backfilled with rock and soil to prevent radioactive gases from escaping. The only elements emerging from the shaft were long cables connecting the diagnostics to recording trailers on the surface.

By the late 1980s, Sandoval was working with a cutting-edge diagnostic system called CORRTEX (Continuous Reflectometry for Radius versus Time Experiments). “It’s fancy time domain reflectometry,” he explains. “You send an electrical pulse down a cable, and when it reaches the end, it reflects. That tells you the cable length, and from that, you can derive the explosion’s yield.”

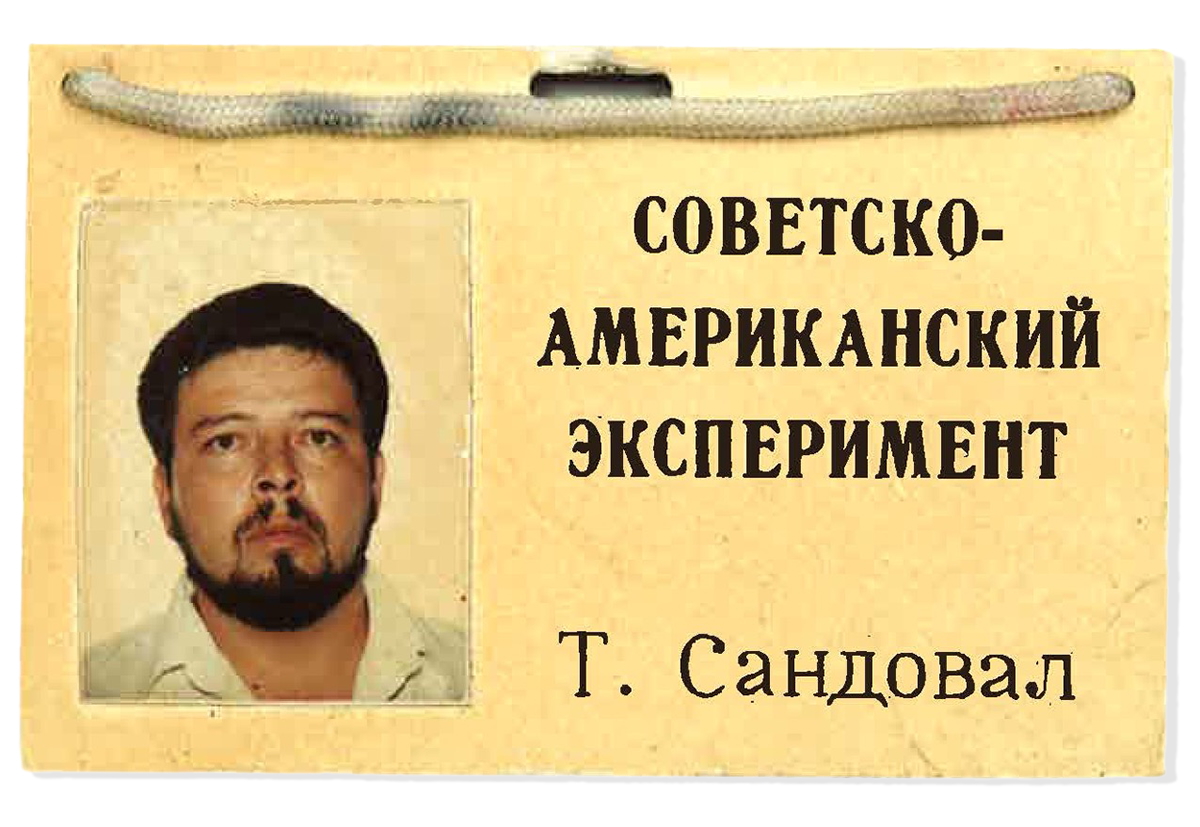

Sandoval built CORRTEX systems at Los Alamos and deployed them in Nevada. The data from CORRTEX was so valuable that soon Sandoval was installing CORRTEX on Livermore-designed tests and even on tests in the Soviet Union. In 1988, Sandoval spent seven weeks at the Semipalatinsk Test Site in Kazakhstan, fielding CORRTEX on a Soviet test as part of the Joint Verification Experiment (JVE), during which U.S. and Soviet scientists worked together at one another’s nuclear testing sites to evaluate methods of measuring the yields of nuclear tests. CORRTEX was a crucial part of this process and helped enable the 1990 ratification of the Threshold Test Ban Treaty, which limited nuclear tests to 150 kilotons.

Infrasound

Sandoval supported the September 1992 Divider test, after which a moratorium on all nuclear testing was put into effect. That moratorium, which is still in place today, meant that Sandoval had to find other work. Sandoval started working with Los Alamos scientist Rod Whitacre and quickly became familiar with yet another type of diagnostic: infrasound. He learned to field infrasound arrays—systems of sensors (usually infrasonic microphones) that can detect sound waves with frequencies below the range of human hearing.

Sandoval traveled all around the country setting up these arrays. “You can get a sense for where things are in the atmosphere and how fast they’re traveling by the way they sound,” he explains. “Among other things, we were looking at how meteors were traveling through and breaking up in the atmosphere.” He pauses and continues. “When the Challenger exploded, we picked it up on three arrays.”

In September 1996, the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty came into effect, and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization (part of the United Nations) needed ways to verify that countries weren’t clandestinely testing nuclear weapons. “That’s when I was going to places like France, Austria, and Germany to talk about infrasound,” Sandoval says.

As the CTBTO dialed in locations for infrasound arrays, Sandoval would go install them. “I was in Ascension Island—in the middle of the Atlantic—for three weeks,” he remembers. “I spent 18 months going back and forth to Fairbanks, Alaska.” He also traveled often to Alabama, Wyoming, and Virginia.

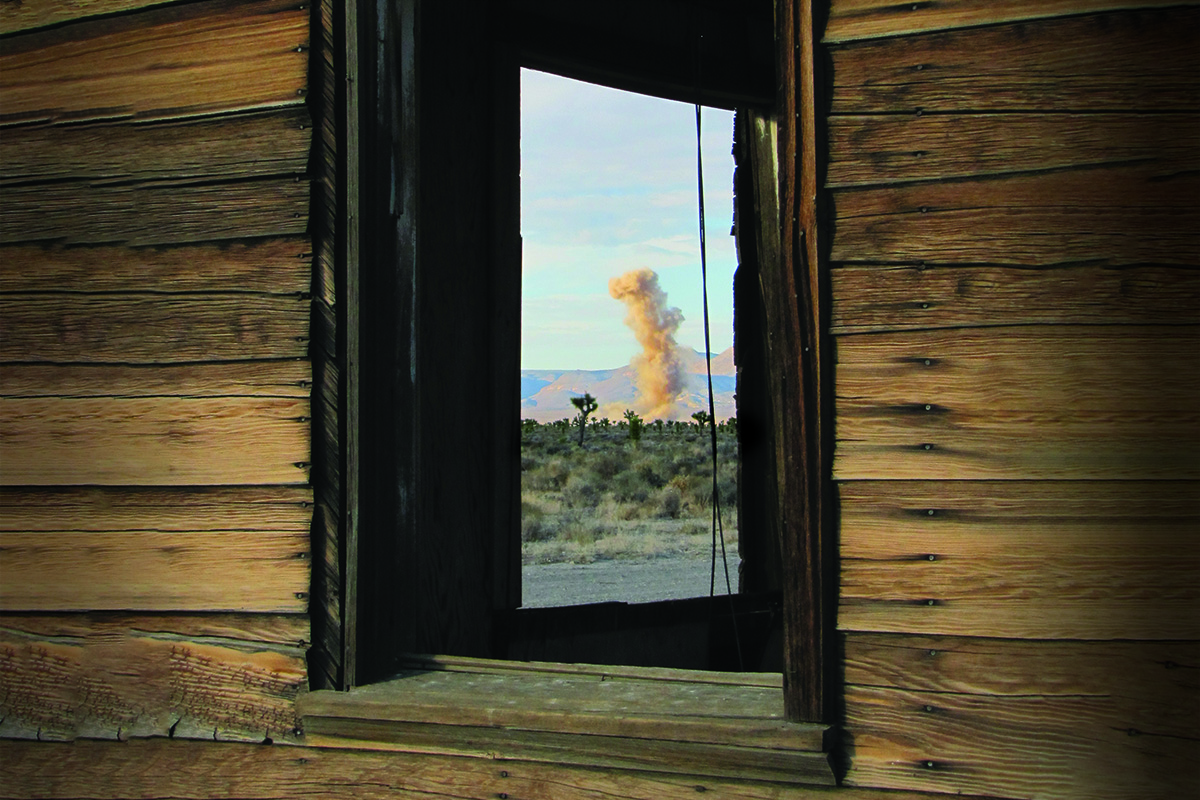

Explosives

Of course, Sandoval, now a Los Alamos employee, was still spending plenty of time at Los Alamos and the Nevada Test Site—both of which had infrasound arrays. “I knew infrasound and CORRTEX,” he says. “So I fit right in at the firing sites—the places where the Lab conducted high-explosives experiments that also incorporated a lot of diagnostics.” Before he knew it, Sandoval was hired into the Dynamic Experiments group and began leading explosively driven experiments. He used tools such as photonic doppler velocimetry, x-rays, and pins to study fragment impact—how pieces of an explosive are propelled outward upon detonation. Some of his work happened at Los Alamos’ Lower Slobbovia firing site, but bigger experiments were conducted at Nevada.

Some work led Sandoval farther afield. In 2008, Sandoval supported Chevron Corporation, which had a cooperative research and development agreement with Los Alamos. That work took Sandoval up to Rifle, Colorado, to study oil shale fracking. “We tried different explosives on different boulders to see how they split apart,” he remembers.

In 2015, Sandoval became the acting group leader for Focused Experiments at Los Alamos and subsequently the permanent group leader. During his tenure as group leader, 300 experiments were successfully executed in one year at the Laboratory. Despite this cadence, Sandoval recognized that the group should be fielding more and bigger experiments. The hang up was at Los Alamos, where increasing numbers of red flag days meant it wasn’t safe to detonate explosives. And because of the Laboratory’s proximity to residential areas, the detonations were limited in size. The solution quickly became apparent: Nevada.

In December 2016, Sandoval stood up the Kappa West firing site at Nevada’s already established Big Explosives Experimental Facility (BEEF). As demand surged for large, fragment-producing experiments, Sandoval built a dedicated team. “We’ve gone from 2 employees there to a team of 24,” he says. “If we have a capability, we will have customers.”

In 2017, Sandoval became the group leader for Los Alamos employees based in Nevada. During this period, he also played a key role in upgrading the NNSS U1a facility—now known as the Principal Underground Laboratory for Subcritical Experimentation—from a Hazard Category 3 to a Hazard Category 2 facility. This reclassification means that greater quantities of special nuclear material can be used for experiments.

Nevada Programs Office

In 2020, Sandoval was on the verge of retirement but reconsidered when Los Alamos stood up its Nevada Programs Office to coordinate Lab work at NNSS. Today, Sandoval leads the Nevada Experimental Operations branch of the office. In this role, he oversees experiments at Kappa West, PULSE, and other areas, such as P Tunnel, where various global security experiments are underway.

Sandoval continues to travel regularly to Nevada, and even after four decades at NNSS, he finds his work as engaging and meaningful as ever. His pride in the Laboratory’s national security mission remains strong, and he’s deeply appreciative of the extraordinary journey it’s taken him on—across the country and around the world.

“It’s been a hell of a ride,” Sandoval says. “Where else is a kid from northern New Mexico going to do stuff like this?” ★