Big booms

The Los Alamos National Laboratory team at Kappa West, a remote firing site in the Nevada desert, handles large explosive experiments.

- Ian Laird, Communications specialist

“Five…four…three…two…one.”

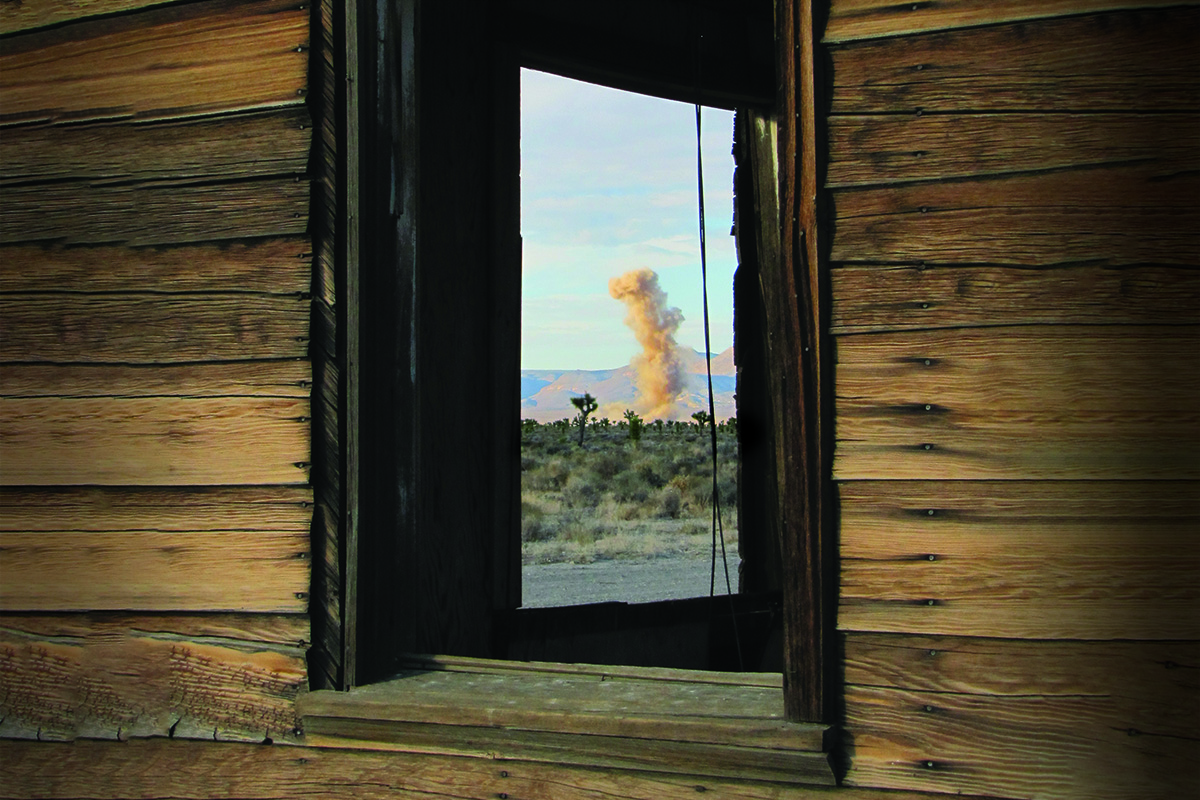

For the second time today, Alex Tafoya’s countdown crackles across handheld radios spread through a cluster of trailers in the heart of the Nevada National Security Sites (NNSS). At zero, in the distance, a fireball emerges against the desert backdrop as more than 560 pounds of explosives detonate.

Seconds later, the sound arrives—sharp, resonant, and chest-thumping. The fireball is gone, replaced by a rising cloud of dust and smoke.

“That was a pretty good one,” murmurs Art Villalobos, his eyes fixed on the dissipating plume. The leader of Los Alamos National Laboratory’s Integrated Weapons Experiments Nevada Operations group, Villalobos has worked for more than 40 years at NNSS, and he knows explosions. Today’s high-explosives (HE) “shots” at Kappa West, part of the Big Explosives Experimental Facility (BEEF) at NNSS, are two of hundreds that Villalobos has overseen.

Nearby, technologist Matthew Teel checks cameras designed to capture the detonation at up to half a million frames per second. Today’s shots will yield no formal data—the purpose is to destroy sensitive parts—but for Teel, it’s practice with his instruments.

The evolution of BEEF

So, what leads up to this chest-thumping explosion? BEEF’s roots stretch back to the 1950s, when its earth-covered bunkers supported imaging of atmospheric nuclear tests. After atmospheric testing came to an end in 1963, BEEF was largely unused until the mid-1990s, when Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, constrained by California’s suburban sprawl, turned to Nevada for HE work.

However, by the 2010s, activity had waned again. That’s when Los Alamos stepped in. Tom Sandoval, then the Los Alamos group leader for Focused Experiments, spearheaded the effort to establish Kappa West in a legacy radiological zone adjacent to BEEF’s original footprint. “BEEF had power, it was flat, it had a bunker,” Sandoval says. “I could do large shots of depleted uranium. My clearance circle was 6,200 feet, and I could fire 2,500 pounds of fragment-producing shots.”

What began as three people working at Kappa West is now a 26-member team that continues to grow. The team members—all Lab employees—support not only Los Alamos programs but also the Department of Defense, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and other federal customers.

The work is diverse: dismantling classified parts, testing blast effects, modeling shrapnel dispersal, and supporting global monitoring efforts. Customers often commit to multiyear campaigns, keeping the calendar full a year in advance.

“We can pretty much do anything done at Los Alamos,” says Villalobos, noting that explosive tests are conducted frequently at the Laboratory. “But Kappa West lets us go bigger.” The site’s remoteness is an asset. Unlike Los Alamos, where wildfire closures or population proximity limit operations, Kappa West provides flexibility. “We don’t face the same constraints,” Villalobos says. “We’re approved for 5,000 pounds of explosives now and we can scale to 50,000 with additional approvals. That’s why demand keeps climbing.”

A day in the field

Reaching Kappa West requires a 45-minute drive north from NNSS’s main entrance. On shot days, the team gathers in a trailer for a safety brief. Today’s work continues a series of weapon dismantlement and disposition (WDD) shots, in which the goal is to reduce classified parts to unrecognizable fragments.

Tafoya, as firing site leader, coordinates and executes the experiments. Fielding coordinator Lewis “Trey” Allen III manages the explosives and the classified inventory. Teel runs cameras, assisted by Kaleb Howard, who has expertise in optical networks and diagnostic communications. Mechanical engineer Justin Cole and electrical engineer Aaron Rogall are both in training to become HE handlers. Deputy group leader Ryan McCombe oversees operations together with Villalobos. With roles clarified, the team disperses and gets to work.

At the firing site, the ground is pockmarked from past detonations. There are three towers of concrete barriers, which have been stacked 20 feet high and bolted together with steel plates. The barriers are equipped with pulley systems that enable some assemblies to be lifted as high as 14 feet off the ground.

Tafoya and Allen prepare sealed metal assemblies containing classified components slated for destruction. The team wraps each assembly with detonating cords, a process that is quick, practiced, and laced with camaraderie. “Most of them have been here at least five or six years,” Villalobos notes. “Everyone’s trained to do everything, so we can adapt as needed.”

Meanwhile, Teel positions his cameras—one of which captures 500,000 frames per second—behind concrete shields, mirrors angled to capture the blast. He knows the risks—shrapnel often threatens delicate optics. Still, each shot is a chance to refine his methods. “I love WDDs,” he says. “They let me test setups without risking critical data.”

Dismantle and dispose

Sitting at the firing console, Tafoya confirms with access control that the firing point is vacant. He inserts a key, counts down, and triggers the explosion, which is inaudible from inside the bunkers.

After a few minutes, team members head back to the firing point to assess the damage and prepare for the second shot to further destroy the assemblies, which have cracked and broken into pieces. These pieces are placed into three 55-gallon drums along with depleted uranium that lis also designated for destruction. The contents are layered with explosives. “We have enough experience where we know what explosives materials need to be used and how much,” Villalobos says. “For experiments where we need data, we will do calculations beforehand, so we know exactly how to position things, but it’s not as precise for WDDs.”

The full drums are wrapped with detonating cords, and the site is vacated once more. However, this time, “We will stand outside,” says Villalobos, positioning himself about a mile-and-a-half away but with a clear view of the firing site. “It should be cool.”

Indeed, 563 pounds of explosives detonating is loud and powerful. A fresh crater marks the ground, surrounded by chunks of warped metal. Some pieces have flown meters away. After determining that the site is safe for reentry, Tafoya holds up a jagged fragment that is still warm from the explosion. Although it will take some time to assess the damage, the drums appear to be sufficiently destroyed.

Not everything went to plan, however. Sun glare washed out one camera’s footage. Another camera got knocked askew by the explosive shock wave and was left facing the wall of the camera shelter. But for Teel, these are valuable failures. “We learn what goes wrong before it really matters,” he says.

Each misstep refines future experiments, where capturing data is paramount. “You see something new every time,” Villalobos says. “That’s the beauty of it. New technology, new systems, new customers—it keeps you motivated.” ★