Protein engineering and a Los Alamos National Laboratory-developed technology has led biologist Hau Nguyen to consider how an enzyme used to degrade plastics could change the future of plastic production.

'This is going to work'

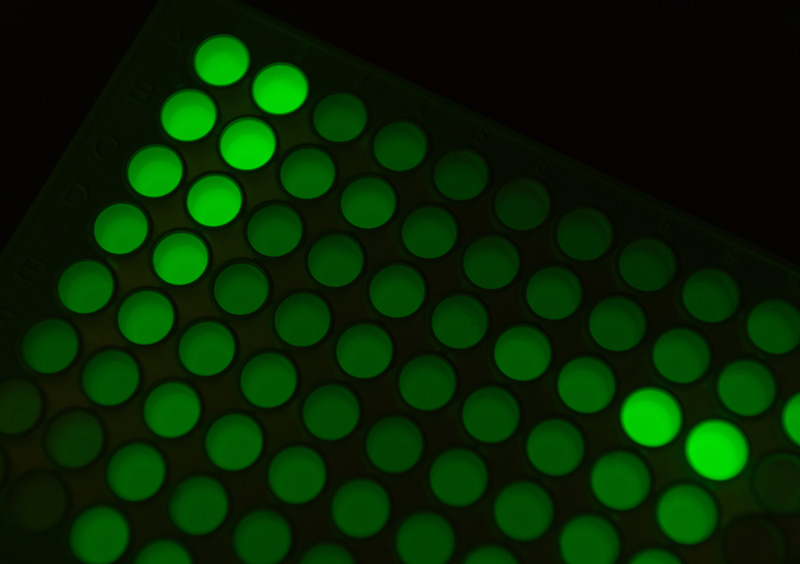

One day in December 2020, Nguyen was checking on her experiment when she felt a jolt of excitement about what she saw: tiny clear circles on an agar plate. "That's when I knew, yeah, this is going to work," Nguyen says.

She had spent months researching and testing various materials to find one for her plastic-degrading-enzyme experiment: it had to be chemically similar to plastic and able to visually indicate if her enzyme was working and to what degree. As Nguyen looked at the sample plate containing the latest option of opaque surrogate material, the clear circles instantly showed that her enzyme had degraded it.

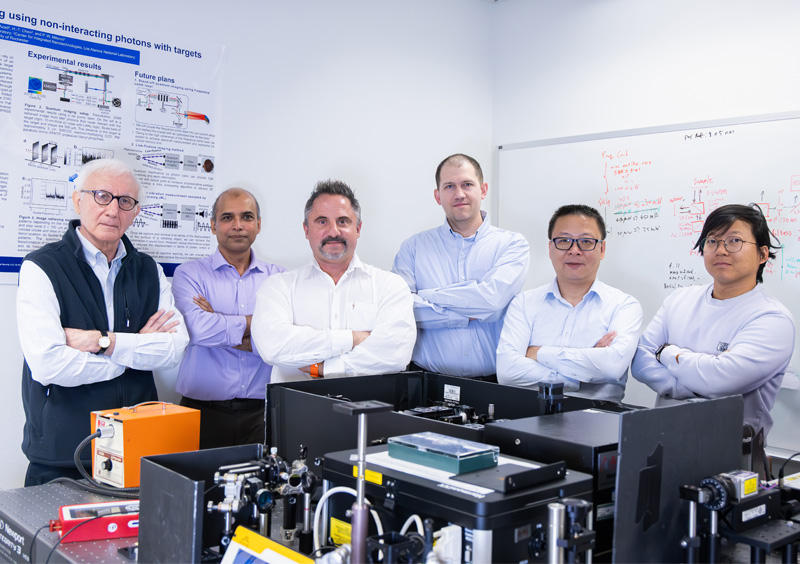

Five years later, the process that Nguyen's team used to develop the plastic-degrading enzyme is a success. Earlier this year, Nguyen, along with colleagues Taraka Dale and Thomas Groseclose, won an R&D 100 Award with special recognition in green technology for Platform to Accelerate Discovery of Tailored Industrial Enzymes (PAD-TIE).

Using PAD-TIE, the team has already developed multiple enzymes that can efficiently degrade plastic into its building block molecules and could be applied to making new enzymes for a multitude of other uses.

Seeing green

Nguyen joined the Lab in 2008 as a postdoc working with Geoff Waldo and Tom Terwilliger in the Bioscience division. Growing up in Vietnam, Nguyen had a strong interest in math and science that began in middle school. In high school, she became more interested in science, especially human health. She studied biology and chemistry and won first prize in the national biology Olympiad.

"For a long time, I thought I'd go to medical school," Nguyen says. "But later in high school, I decided against it because I didn't like the sight of a lot of blood."

Despite her change in focus, Nguyen's love for science "grew and grew" during college, and afterward she moved to the United States to pursue a Ph.D. in molecular biophysics at Florida State University.

Nguyen specialized in studying protein structures, but Waldo was doing something that truly fascinated her: protein engineering. When Nguyen joined Los Alamos, Waldo had already developed a few noteworthy techniques using a molecule called “green fluorescence protein” (GFP). He devised a strategy, called "split-GFP," that causes a protein to emit a green glow when it is folded correctly. Protein function is dependent on structure: when proteins are misfolded they are unstable, won't stay in solution and can't function properly.

"Using split-GFP, we can determine when a protein is soluble or stable, which helps facilitate making high-quality crystals of the protein so we can study its structure faster, or to decide which version of a protein is best to use in an experiment," Nguyen says. Waldo's split-GFP technique was becoming widely used and regarded. (The 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to three scientists for the discovery and development of GFP; although Waldo wasn't one of them, his involvement in the field earned him an invitation to the ceremony.)

When Nguyen joined Waldo's lab, she helped develop several new versions of the "split" systems that could further advance protein analysis using multiple fluorescent proteins and different colors.

Proteins for good

Nguyen left the Lab for a few years to launch a GFP-based biotech company focused on drug discovery. There, she screened for new molecules that disrupt critical protein-protein interactions. During that time, she also worked as a research scientist at the New Mexico Consortium, leading a team of researchers to develop novel protein therapy for citrus greening disease. However, around 90% of startups fail and, unfortunately, her effort was not an exception.

Nguyen returned to the Lab in early 2019 and continued to use GFP and the split approach for many of her new projects.

Solving problems with protein engineering

"I like to think about how to solve real-life problems and how to apply protein engineering in ways that can benefit humans," Nguyen says.

And that's exactly what she's been doing. Over the past few years, Nguyen has worked on a wide range of projects that could help find solutions. One project has been to predict if molecules are toxic, characterize toxin structures and engineer protein binders to advance new medical countermeasures to treat toxin exposure. Another project has her looking into engineering new split-fluorescent protein systems as reagents for detection test kits.

And then there is PAD-TIE.

"We invented PAD-TIE so that we could rapidly evolve enzymes tailored for new purposes," Nguyen says.

The first problem the team hoped to tackle with their enzyme technology was plastic waste. Conventional (mechanical) plastic recycling breaks plastic down into tiny pieces that can only be reused for a limited number of times, often to produce low-quality items. Alternatively, if plastics could be chemically deconstructed using enzymes (without toxic chemicals) into their building block monomer units, those building blocks — much like Lego bricks — could be rebuilt into new, high-quality plastics, which would reduce not only current plastic waste but also future plastic production.

Branching out with a new vision

Nguyen's team started with an enzyme called "leaf-branch compost cutinase" (LCC) that was discovered in Japan. LCC can break down the waxy coating of leaves and has been shown to also degrade polyethylene terephthalate, a common plastic used in food containers and other single-use items. Research groups from all over the world have tried to enhance the LCC enzyme — and one version is already being used by a recycling company in France — but further improvements are needed to boost efficiency and make the process economically viable.

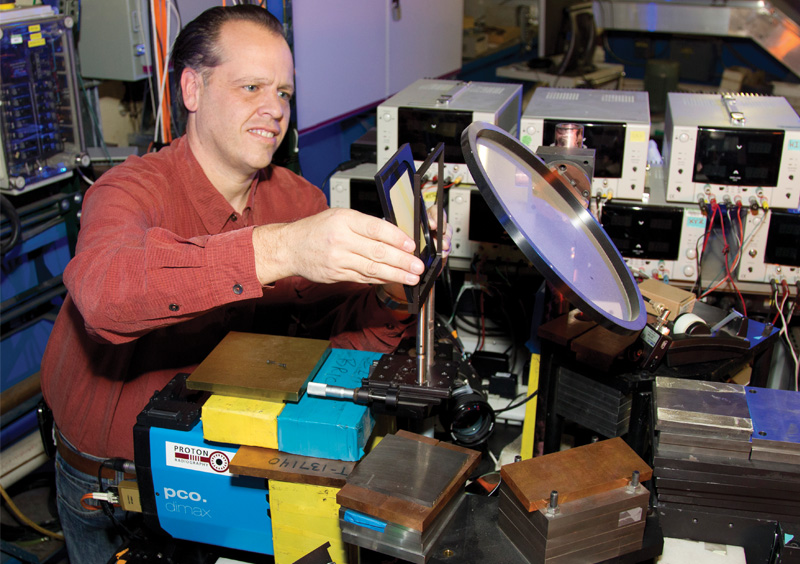

The PAD-TIE team set out to improve LCC's degradation performance and production yield using directed evolution, relying on two key approaches: surrogate substrate-based and split-GFP assays.

- First, they took the DNA sequence of LCC and made a library of tens of thousands of new enzyme candidates, hoping that some would randomly gain beneficial mutations.

- Then they tested and screened the enzyme candidates for their improved ability to degrade plastic, selected the best ones, and repeated the process until they felt they'd made a significant improvement.

Each cycle produced enzymes with increasingly better qualities for plastic degradation. This process is known as directed evolution because it mimics natural evolution, with the scientists creating selection pressures to get enzymes with high catalytic activity and stability under high temperatures — both important features for industrial recycling.

The split-GFP system is key to PAD-TIE because it makes it possible to screen large libraries of variants quickly and without the need for expensive equipment.

As the candidate enzymes broke down the plastic (first using the surrogate material and later actual PET), the empty spaces (the clear circles) showed where the best performing enzymes were located. GFP was used to visualize the amount of enzymes present: a more intense green glow coupled with large, clear circles emanated from enzymes that were both highly active and produced in large quantities.

Advancing two high achievers

Using PAD-TIE, Nguyen and her colleagues developed two unique enzymes that showed high levels of activity breaking down PET at high temperatures and have the potential to be used in industrial plastic recycling. They named one LCC-LANL and the other PHL7-Jemez.

In addition, the project demonstrated that PAD-TIE is an easy-to-use, highly adaptable and affordable platform for developing new enzymes for any industrial process.

"Because plastic is a solid material, it is challenging and expensive to do high-throughput screening using standard instruments," Nguyen says.

The team's use of the split-GFP system coupled with a surrogate substrate was key to the success of PAD-TIE. The split-GFP assay eliminated certain costly and time-consuming steps (such as protein purification). The surrogate-based assay quickly showed the enzyme activity level so the researchers could select only the most promising enzymes to test on actual plastic. Together, these methods helped PAD-TIE give a lower false negative and false positive signal about enzyme activity, stability and production level.

"People have used GFP in the past for several types of detectors, but PAD-TIE is a creative new approach, and the green glow of the split-GFP system is what makes it possible," Nguyen says. "It's nice to see this technology that started here at Los Alamos get recognized."

Giving plastics the one-two punch

Conventional plastic recycling has problems:

- It breaks the plastic into tiny pieces that can only be reused a few times.

- It usually results in low-quality products.

But there's a better way:

- Nguyen's invention can create enzymes to chemically break down plastic into its building blocks (called monomers).

- Companies could use these enzymes to make brand-new, high-quality plastic products without using toxic chemicals.

- This would help solve both our current plastic waste problem and reduce the need to make new plastic in the future.

Watch this YouTube video to learn more.