Los Alamos National Laboratory physicist Diego Dalvit has had a lot of great ideas over the years, but he says this one feels different in part because of how it came to him. He has conceived a radar system that would use quantum states of light to detect faraway objects. A specialized frequency comb laser recently delivered to the Laboratory is key to the potential breakthrough design, and experimentalists are about to begin testing Diego’s concept.

Memory storage issues have hampered the promise of remote quantum sensing despite international attempts to make this mind-bending technology work since 2019, when it was attempted for the first time. Diego says he thinks he’s found a solution.

“I am fully engaged in a groundbreaking idea on remote quantum sensing that I got in the shower in December 2022 — the Eureka moment of my life,” Diego says.

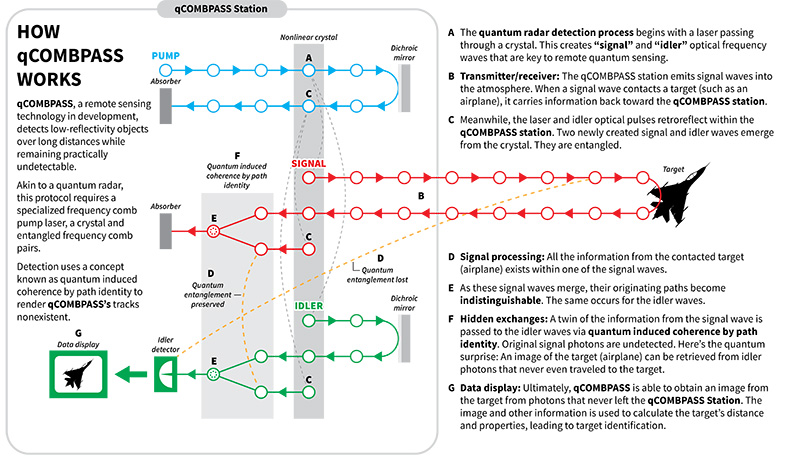

If his scheme, dubbed qCOMBPASS, is proven to detect faraway objects with finer sensitivity and resolution than traditional radar systems, it could lead to powerful new technology for defense and communications.

While sipping an espresso in his Theoretical division office, Diego recounts the unusual series of events that emboldened him to pursue this challenge.

Combing through options

Diego, an expert in quantum optics, has mostly built his 26-year career around high-risk, high-reward science funded by the Laboratory Directed Research and Development (LDRD) program. At a brainstorming meeting with other scientists in 2022, he suggested their next project should explore quantum sensing, an emerging field and a subset of quantum optics. From research he did 15 years before, Diego knew which quantum states of photons offer a quantum advantage for remote sensing.

In passing, Jonathan Cox, a scientist in the Intelligence and Space Research division, mentioned he was using frequency comb lasers, an unfamiliar area of optics for Diego. These specialized lasers allow scientists “to measure and control light waves as if they were radio waves,” according to the National Institute of Standards and Technology, plus they work over long distances and play a role in classical remote sensing.

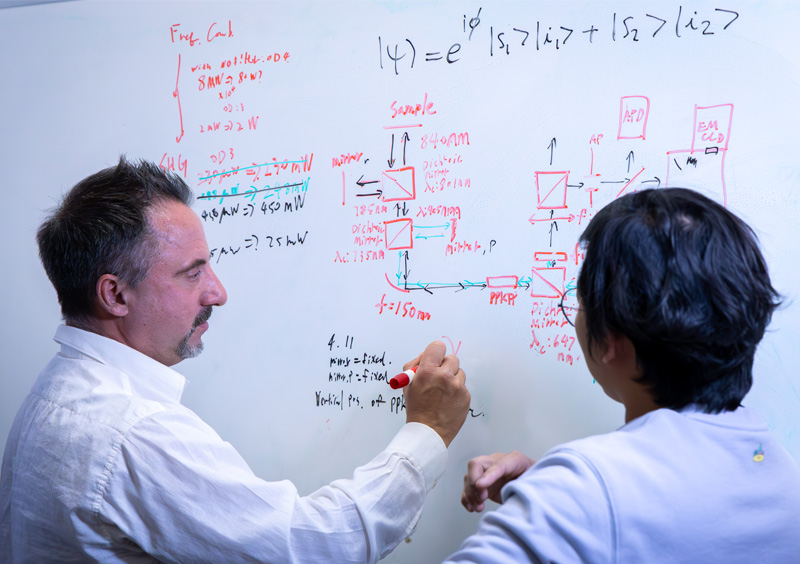

Feverishly, Diego burrowed in, and soon he had a plan and a name. qCOMBPASS is an abbreviation for “quantum frequency combs with path identity for remote sensing of signatures.”

Eureka moment replay

The evening of the LDRD brainstorming session, Diego began reading technical papers to understand the state of the technology. He was drawn to a picture of an airplane on a quantum sensing paper. “I love airplanes,” he says. “When I was a kid, my grandfather took me every Friday after school for picnics at Buenos Aires airports to watch planes, and that stays in my heart.”

Although an airplane was depicted in the paper, Diego realized the authors’ scheme did not operate across the skies. It was limited to hundreds of meters at most. He couldn’t find any other prototypes that broke that barrier.

Diego wondered: How can we extend the sensing range to detect faraway objects, from here to the moon or from satellite to the Earth or from satellite to satellite?

Weeks later, qCOMBPASS was born out of an intense experience.

“I was taking a shower and then my brain started to work. My line of thought was: I have to store a photon for a long time, but it cannot be done. How can I do remote sensing without storing a photon?” Diego recalls.

While puzzling over potential solutions, he says he entered a trance-like state in the shower. Then came the aha moment: he believed the answer was to use frequency comb lasers, which he had learned about two weeks before. These super-stable lasers, which garnered a Nobel Prize in Physics in 2005, send spaced pulses that are identical to each other.

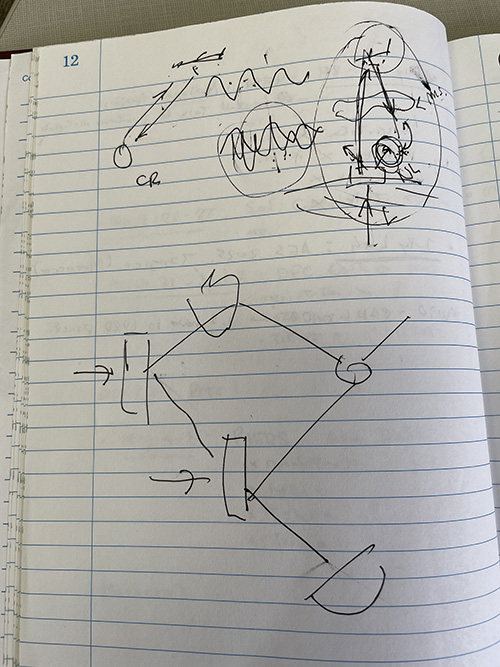

Diego emerged with a clear sense of how to overcome quantum storage and photon loss challenges over long distances. He jotted down the ideas, which mashed together methods from a 1991 University of Rochester paper, light squeezing technology to make photon pulses more robust against loss in the atmosphere and frequency comb lasers.

“I started to shake,” Diego says. “I immediately saw the implications … this could sense and image an object faraway with precision better than classical physics and with many other advantages. One advantage is it could detect low-reflectivity objects in very noisy environments, so it’s basically anti-stealth technology.”

Sprinting from idea to proposal

The following morning, he texted Marcus Lucero, science and engineering program manager for the Lab’s National Security and Defense Program Office, to set up a meeting. Days later, he dropped off a 35-page technical overview of his vision.

“He’s a very unique and focused person who is an absolute delight to work with,” says Marcus, who knows him well. “He overdelivers on everything.”

Marcus invited program managers and quantum scientists to hear Diego’s presentation, and “they picked it up almost immediately,” he says.

In theory, qCOMBPASS would be able to collect high-resolution images of objects, as well as information about distance, velocity and material composition. Diego’s method would be extremely hard to detect, plus provide intrinsic security against jamming and spoofing by adversaries.

Mark Wallace, then of the Intelligence and Emerging Threats program office at the Laboratory, envisioned potential applications in direct service to national security.

“I was impressed by Diego’s ability to explain a complex set of ideas in a coherent way; that is often a big challenge when dealing with quantum effects,” Mark says. “Once I understood it, the potential for nearly unlimited range got me most interested as that means there is a clear path to a broad set of applications and not just interesting phenomena in a laboratory.”

Hand calculations, peer review

Diego reconvened with the LDRD team to prepare a funding proposal. qCOMBPASS was just an idea and now he had to do the math, which he did with good old pen and paper (he’s not a computer geek). Other scientists checked his calculations for flaws, at his request.

Next, he contacted “his idol,” retired Laboratory Fellow Peter Milonni who is famous for his quantum optics work. Diego was thrilled with his encouraging response. But a former mentor cautioned Diego, “This is too good to be true.”

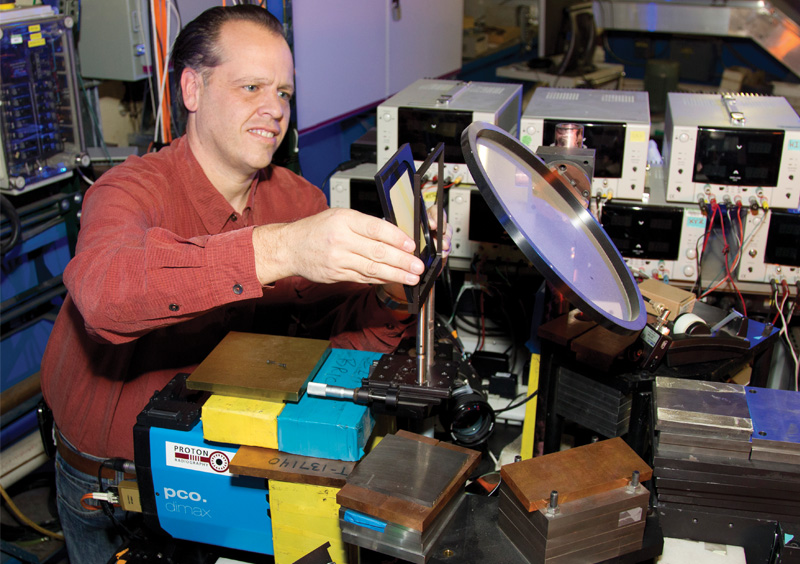

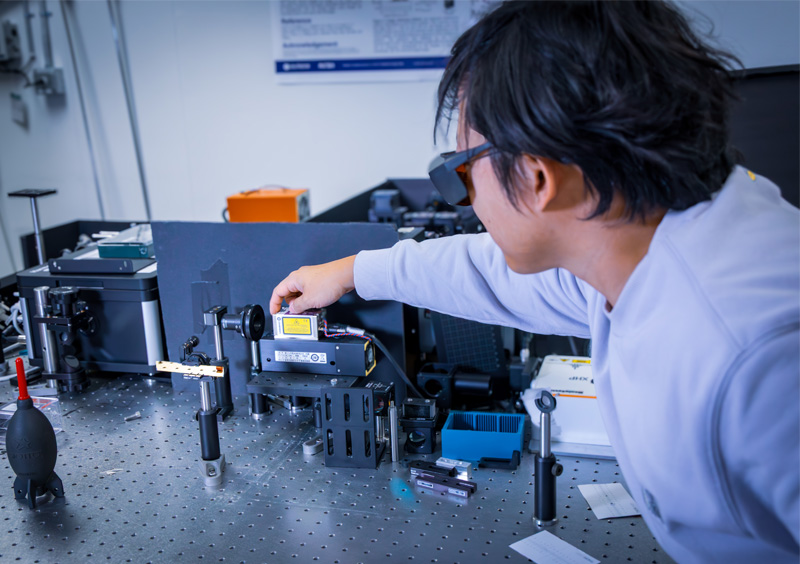

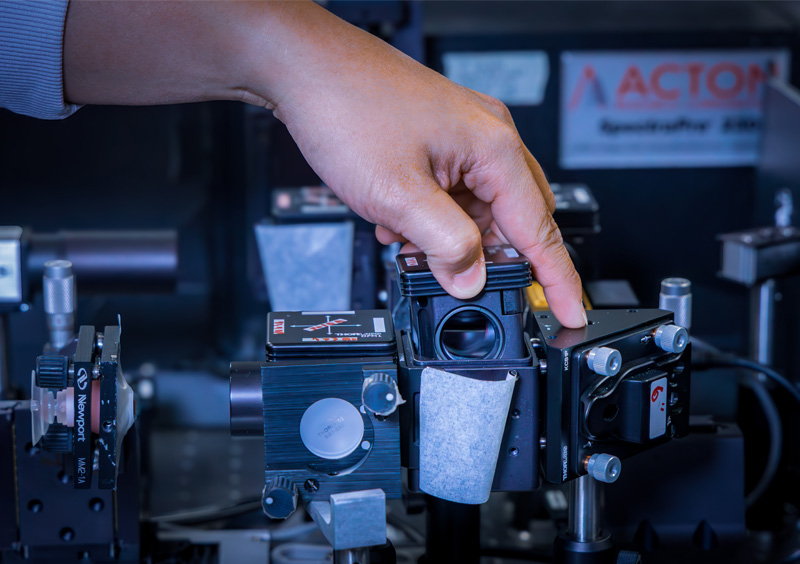

Diego enlisted the help of experimentalists at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies (CINT). With success, Los Alamos postdoctoral researcher Yunseok Choi repeated the 1991 Rochester experiment using continuous wave lasers and quantum-induced coherence by path identity to image an object at a close distance in the lab.

Refining theory, rejection letters

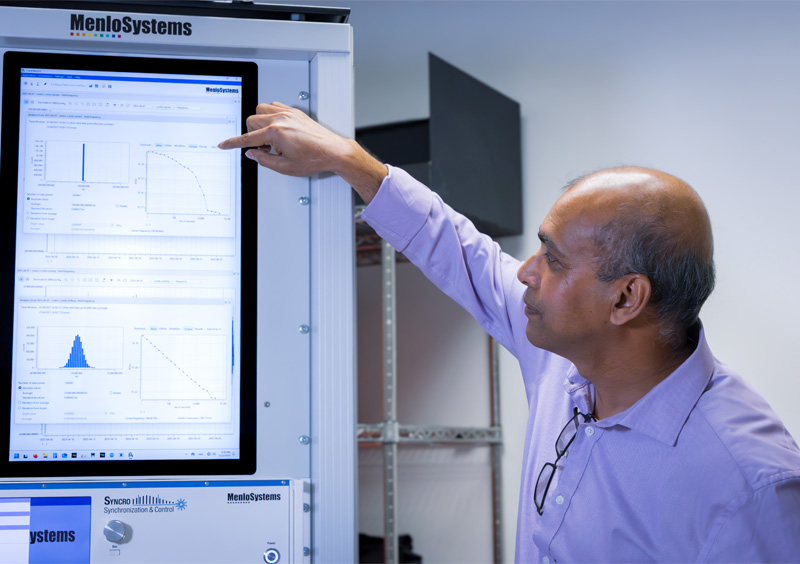

On Diego’s second attempt, he received one-year LDRD-Director’s Initiative funding, which covered the frequency comb laser, and the team began the project in January 2024.

The first task was the development of the theory of reflectivity sensing with undetected photons. Los Alamos Physicist Tyler Volkoff worked with Diego to incorporate squeezed states of light for ultra-precise measurements. The second task was to analyze the feasibility of an experimental realization. CINT Researcher Houtong Chen had long discussions with Diego and helped design potential schemes for the experimental demonstration.

It all seemed to check out, and Diego was convinced “this is the most important result of my whole career.”

Although Diego had trouble getting published because of the theoretical nature of the work, Physical Review X, a journal of the American Physical Society, published “Quantum frequency combs with path identity for quantum remote sensing” in December 2024.

A year ago, the Lab filed for a patent on the theory of quantum radar with undetected photons. The Lab’s Richard P. Feynman Center for Innovation is now a supporter of the work through its Strategic Investment Initiative program.

Experiments and field demos

This year, the qCOMBPASS team hopes to take a step toward demonstrating what might be the world’s first credible remote quantum sensing scheme. Los Alamos’ Abul Azad is leading the effort, which involves repeating that same 1991 Rochester experiment — only this time with the Lab’s new frequency comb laser. Something similar was done with this specialized laser in South Korea, so that’s why they are optimistic.

“I am excited to see the partnership developing between the theory Diego has come up with and the experiment expertise of Abul,” says Mark. “The nature of the innovation necessitates testing it over significant distances to demonstrate a practical benefit but first requires a series of increasingly complex laboratory measurements. Their approach looks sound in doing that.”

Current technology suffers from memory storage problems because photons can only hold onto images for a few milliseconds. Diego’s method doesn’t need a quantum memory, a compelling feature that could overcome barriers to long-distance sensing.

Diego and his team propose to solve the memory storage problem by employing frequency comb lasers to extend the coherence time to more than 2,000 seconds, long enough that the initial signal stream can reach its target and return (but are undetected), and a twin stream of photons can reach a detector. The image of the target is retrieved from the twin photon pulses that never traveled through the skies.

This innovation is expected to enable quantum remote sensing at distances of tens and even hundreds of kilometers, he says. If it works in the lab, then the team will move on to field experiments.

“The quantum sensing scheme we have developed achieves a sensing capability that is impossible in classical physics,” says Diego.

With qCOMBPASS, the Lab could gain the capabilities to become a world leader in quantum photonic technologies, including quantum sensing, imaging, computing, networking and communications, he says.

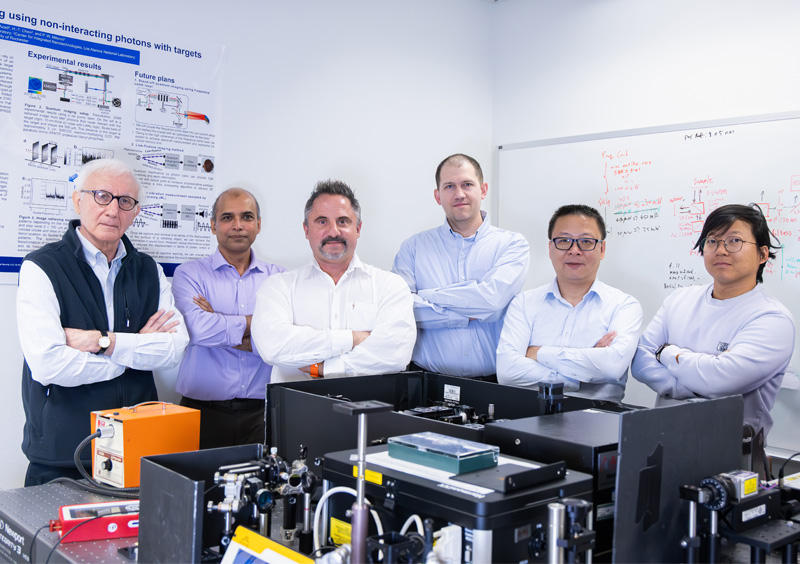

Meet qCOMBPASS innovators

- Diego Dalvit, Tyler Volkoff (T-4)

- Yunseok Choi, Houtong Chen, Abul Azad (MPA-CINT)

- Peter Milonni (Lab Fellow, retired)

Want more technical details about qCOMBPASS? Read this story.