In a recent study of the contiguous United States, Los Alamos National Laboratory researchers found that the risk of disease from hantavirus is higher in drier, underdeveloped geographic areas with more socioeconomic vulnerability and increased numbers of unique rodent species. This is the first study to examine the combined effects of multiple variables — including socioeconomic, environmental, land use and rodent species — to determine which are most likely to predict the risk of people contracting hantavirus.

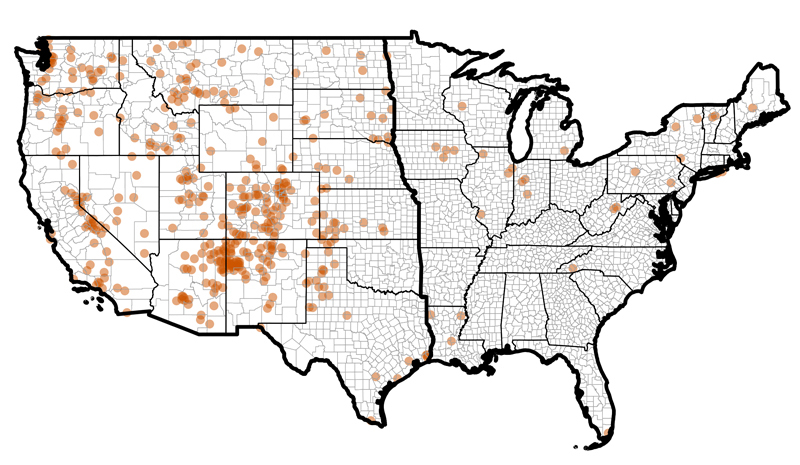

“We ran each of these variables separately — looking at where people are most at risk given just the environmental variables, just the land-use variables, etc. — and then we combined them all,” said Morgan Gorris, a scientist at Los Alamos and lead author on the study published in Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. “This gave us a map of where people are most at risk of being exposed to hantavirus and contracting hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS).”

HPS is an acute respiratory illness with a mortality rate of about 35% in the U.S. Humans become infected with hantavirus when they inhale the airborne particles of feces and urine of disease-carrying rodents. By estimating the long-term risk of contracting the disease across large geographic areas, this study can provide public health officials with information about populations most at risk for contracting hantavirus and the potential drivers of disease risk so they can target appropriate disease mitigation strategies.

The researchers used Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data of U.S. hantavirus cases from 1993 to 2022. When they combined the socioeconomic, environmental, land-use and rodent population variables, the models indicated that the drier western United States is at higher risk for hantavirus.

“The drier air in the West likely allows the virus to persist in the environment and aerosolize rather than get washed away into storm drains, as it probably does in the wetter eastern U.S.,” Gorris said. “Hantaviruses can survive in rodent feces for up to 15 days, so the drier climate in western states like New Mexico naturally allows infected feces to more easily accumulate in areas with human activity, like outdoor working spaces around sheds and barns.”

The researchers also found that “fringe” geographic areas, where human development intersects with natural rodent habitats, are at a higher level of risk for humans contracting hantavirus.

This is not, however, a result of more rodents living in these areas, but because of the stress put on their habitats, according to Andrew Bartlow, a scientist at Los Alamos and coauthor on the paper.

“This is common with diseases that pass from animals to humans,” he said. “When humans encroach on animals’ natural habitats, the animals’ stress levels increase, resulting in higher viral shedding, which increases the likelihood that humans become infected. We see this all over the world. It’s why it’s so important to establish buffer zones between human development and animal habitats.”

The authors also found that increased rodent richness — or the number of unique rodent species present in a specified geographic area — was associated with increased hantavirus risk. They noted that this warrants further study into how the abundance and community composition of rodents could impact long-term risk.

“Our hope is that the risk maps we’ve developed can help public health officials develop plans for mitigating hantavirus, especially for the most susceptible populations,” Gorris said. “They can also be used to further investigate regions estimated to be at high risk for hantavirus where disease cases have not been as common but may be underreported.”

Paper: “Hantavirus is Associated With Open Developed Areas and Arid Climates, Highlighting Increased Risk in the Western United States.” Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. DOI: 10.1155/tbed/7126411

Funding: This work was supported by the Los Alamos National Laboratory Technology Evaluation and Demonstration program.

LA-UR-25-31003

Contact

Public Affairs | media_relations@lanl.gov