Testing at Tonopah

Mock assemblies of nuclear weapons are put to the test just 160 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

- Ian Laird, Communications specialist

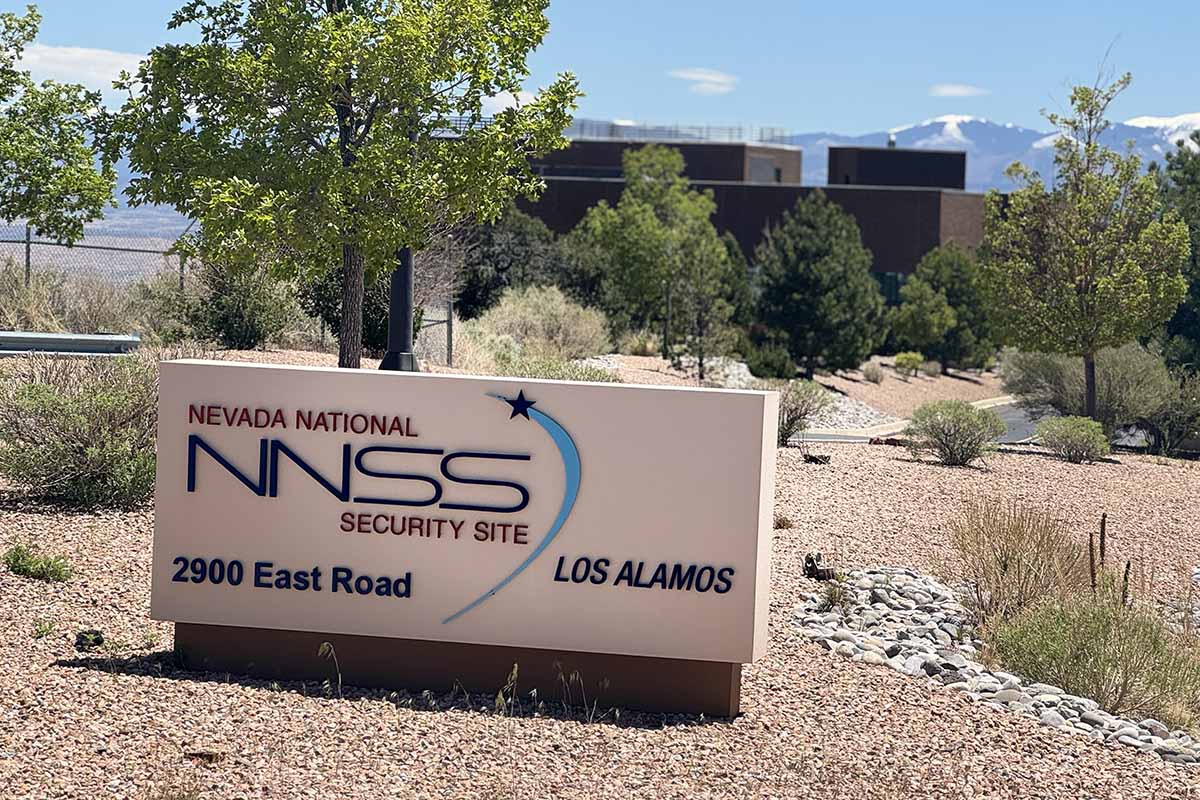

U.S. Air Force planes streak across the skies above the Tonopah Test Range (TTR), a remote military installation located about halfway between Reno and Las Vegas, Nevada. The planes support flight tests that help the Department of Defense and National Nuclear Security Administration labs evaluate the pathing, performance, and survivability of nuclear weapon assemblies.

At TTR, flight tests are limited to the two bombs in the U.S. nuclear stockpile: the B61, designed and maintained by Los Alamos National Laboratory, and the B83, managed by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. The tests use mock assemblies containing no nuclear material and often no high explosives. A nuclear-capable aircraft releases the test unit over a designated target zone.

Los Alamos research and development engineers Casey Door and Tim Rushenberg are the only full-time members of the B61 flight test team. A significant part of their role involves coordination with military partners, particularly the Air Force. “There are two formal meetings a year, led by Air Force Global Strike Command and Strategic Command,” Door says. “Outside of those, we work to keep those relationships strong.”

These biannual meetings are used to set test schedules and determine airspace availability. Once dates are confirmed, the focus turns to building test assemblies. “Some are low-fidelity, using surrogate materials,” Door says. “Others are high-fidelity and include nearly every component we can safely use.” Thanks to decades of B61 testing and a large repository of past assemblies, Door and Rushenberg can often develop the right configuration for a specific goal. Their work spans multiple B61 variants, including the recently fielded B61-13.

Combined, Door and Rushenberg take about a dozen trips to TTR annually, with each test spanning about a week. The process includes extensive setup and coordination. On test day, the aircraft performs a communications check followed by dry runs over the target area to ensure the aircraft is meeting the test parameters. Once alignment is verified, a “hot pass” is conducted and the mock weapon is released.

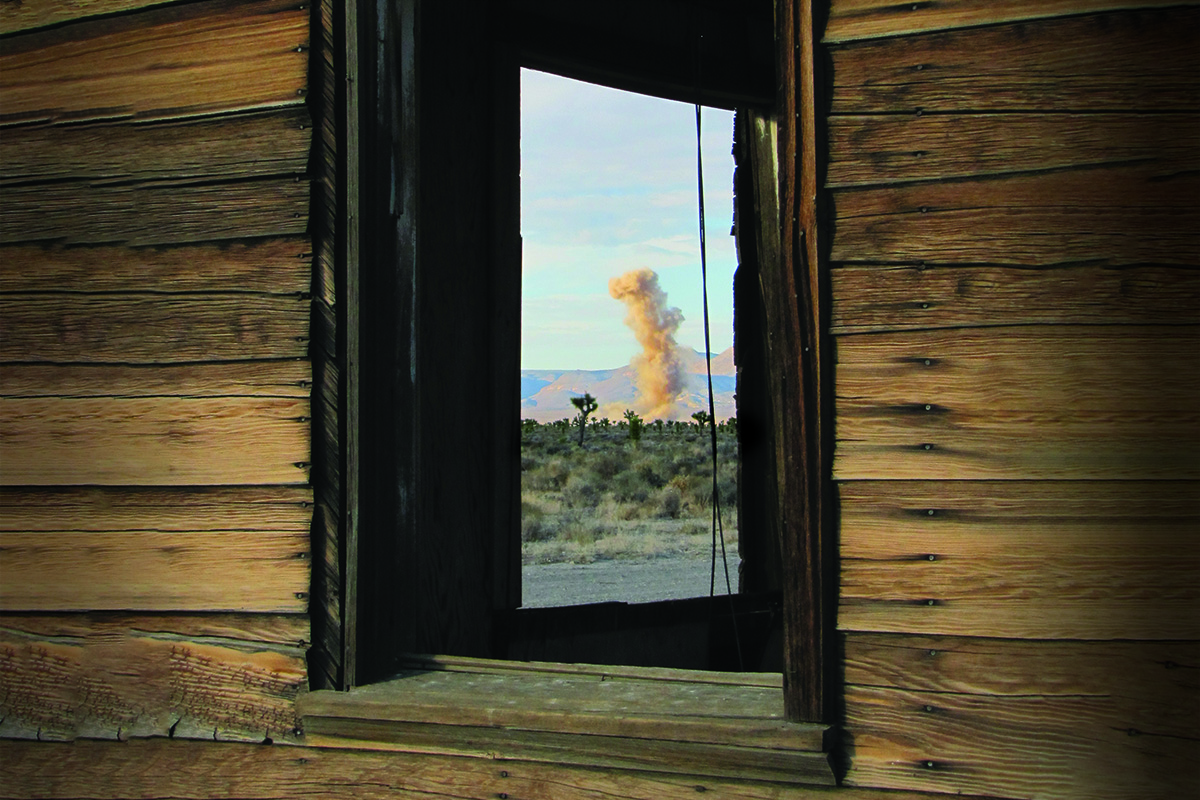

Data collection begins immediately. Instrumentation on the plane and assembly provide live readings, and while that telemetered data can be hard to interpret as it streams in, once analyzed, it helps the team evaluate if the flight and release went as expected. “The live feed comes in fast,” Rushenberg notes. “Sometimes we get what we need right away. Other times, recovery is required to get the necessary data.”

Recovery is mandatory after each test to retrieve materials and prevent contamination. Timing varies—some units are recovered immediately, others during batch trips. The data collected helps evaluate component function and environmental response. According to Door, the team has a high success rate in both test execution and data quality.

One persistent variable is the weather. “We’ve had hurricane-force winds, calm heat, and even snow in June,” Rushenberg says. “One time, we almost didn’t make it out of the valley before the roads closed due to snow. It can get wild.” ★