Hold everything

Los Alamos containment scientists ensure no contamination is released.

- Jill Gibson, Communications specialist

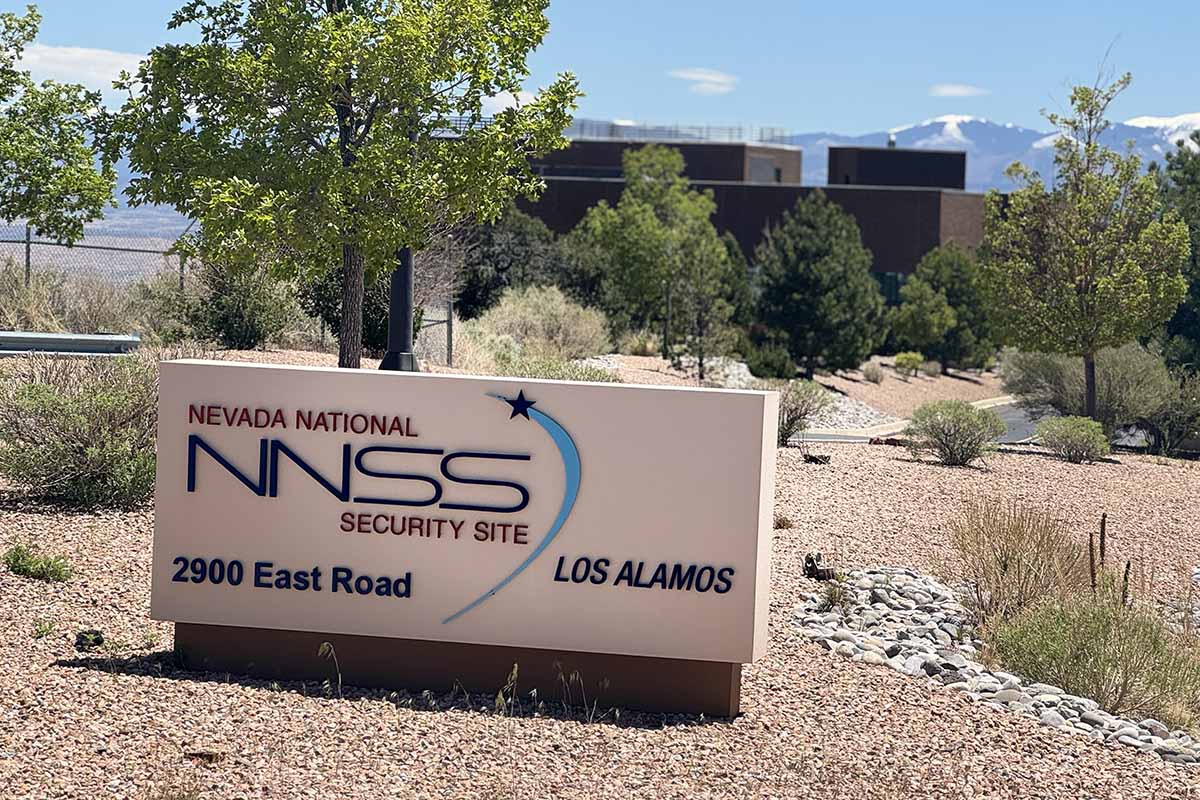

One of the primary challenges of conducting nuclear experiments beneath the Nevada desert is ensuring no radioactive material escapes into the environment. This is where the science of containment—a combination of engineering, geophysics, geology, thermodynamics, shock physics, radiological science, and more—comes into play.

“Any time you have high explosives interacting with special nuclear materials, you must follow containment protocols,” explains retired geophysicist Chris Bradley, a guest scientist in the National Security Earth Science group at Los Alamos National Laboratory. “We are obligated by treaty not to release any radioactive material.”

Containment became required after the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, which pushed full-scale tests of nuclear devices underground. Since then, Los Alamos scientists have pioneered advanced techniques to prevent radioactive release.

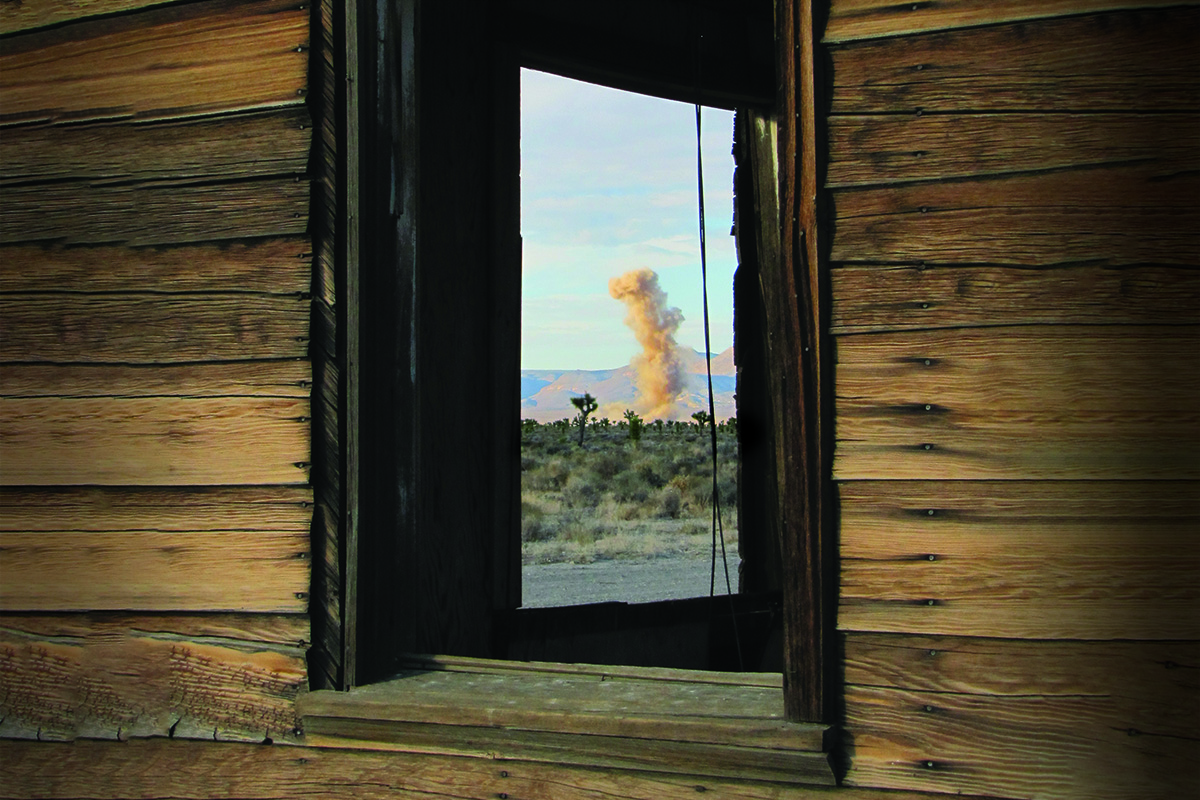

Wendee Brunish, a retired Los Alamos containment scientist, says that simply moving testing underground provided the first step. “It was a huge adjustment, but we found out that the minute we did go underground, if you just drilled a deep open hole and put the bomb down at the bottom of the hole, you would reduce by more than 90 percent the amount of radioactivity released to the atmosphere.”

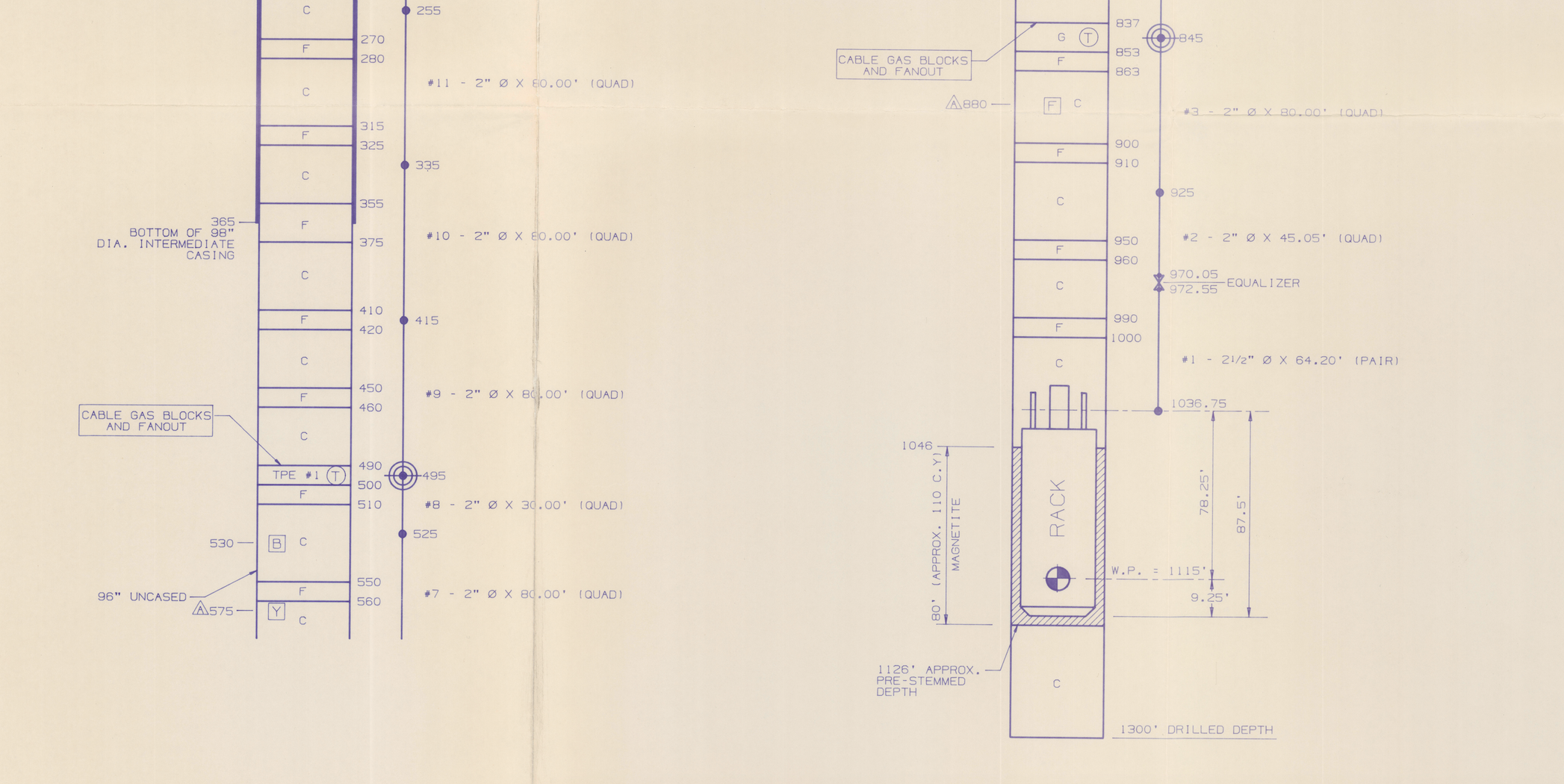

During full-scale nuclear testing, researchers lowered devices into deep vertical shafts and backfilled the holes with stemming materials, mixtures of gravel, fine sand and magnetite, concrete, bentonite clay, and even ball bearings. The “stemming column” acted as a plug to stop the escape of gases, debris, and radioactive material. “It was a huge win without even doing anything fancy,” Brunish says. “Right away we were like, this is obviously something we need to do.”

In 1992, the United States declared a moratorium on full-scale underground testing, but containment operations and research have continued, sustaining the Lab’s expertise.

“Containment science represents decades of effort, and the work is continuing,” says Michelle Bourret, the Los Alamos containment team lead. The subcritical experiments now conducted in Nevada must meet strict regulations to contain any possible radioactive release.

“The Los Alamos containment team takes part in all operations and fielding of the Lab’s subcritical experiments,” says containment scientist and geophysicist Garrett Euler, also of the Lab’s National Security Earth Science group. “Inside the underground tunnels, we have bulkheads, barriers, steel, and concrete. And the ground is also a good containment barrier,” he says, noting that containment requires a thorough understanding of how energy interacts with the earth.

Along with containment, subcritical experiments also rely on confinement—confining the explosion and radioactive materials in specially constructed steel vessels to minimize any release. Containment and confinement work together to ensure all Department of Energy safety standards and regulations are met.

Bourret says that her team has expertise with shallow- and deep-test borehole preparation, diagnostic placement and optimization, ground fracture and cratering, and many other aspects related to both historic and current underground testing. “Our research in underground experimental site preparation, characterization, and signature science all support national and global security,” she says.

Containment science also plays a significant role in global monitoring of explosions and low-yield testing. “One of the many things containment scientists understand is how to look at a pile of dirt and identify what took place,” Euler says. “We conduct experiments using tracer gases as surrogates for special nuclear materials and have developed the techniques and advanced instrumentation and modeling to monitor nuclear test activity around the world.”

Bourret adds, “Although since the testing moratorium, scientists no longer face the issue of containing radioactive releases from nuclear device detonation, our ongoing commitment to containment research enables treaty compliance and monitoring and works to maintain test readiness.” ★