Fired up

Chemist Levi Lystrom has a passion for pottery.

- Whitney Spivey, Editor

On a Wednesday evening at the Fuller Lodge Art Center in downtown Los Alamos, eight beginner potters gather around 5-gallon buckets labeled with names like nutmeg, juicy plum, and Norse blue. Each bucket contains a glaze—a liquid into which ceramic mugs, plates, and bowls are dipped. Once fired in a kiln, each piece will emerge with a colorful coating.

“Understanding the chemical process during firing and cooling is fascinating,” says Los Alamos National Laboratory scientist Levi Lystrom, who is teaching the class. “As a chemist and a lifelong learner, for me, the most enjoyable part of pottery is glaze formulation.”

As he dunks a ramen bowl into a vat of lavender mist, Lystrom tells his students about experimenting with dolomite, a common lawn supplement, to create a matte glaze. “The calcium and magnesium in the dolomite crystallize as the kiln cools,” he explains. “These crystals alter the surface and appearance of the glaze, producing a unique effect.”

Lystrom’s enthusiasm grows as he describes soda firing, a technique he first encountered as an undergraduate at North Dakota State University (NDSU). He recalls tossing salt into the flames of a hot kiln. “The vaporized sodium interacts with the surface of the pottery in the kiln,” he explains. “Unloading the kiln was always exciting—the results were unpredictable and one-of-a-kind.”

A lifelong obsession

Lystrom’s love for pottery began more than 25 years ago. “I remember my elementary school art teacher making a pot on a kick wheel,” he recalls. “I was mesmerized by the process.” Determined to try it himself, he bought a toy pottery wheel at a garage sale. “It kept me interested,” he says, “but ultimately led to frustration because a toy can’t do what a professional wheel can.”

In high school and college, Lystrom finally had access to professional pottery wheels and formal instruction. He devoted himself to the craft. “I became obsessed,” he says. “It wasn’t unusual to see me walking around campus covered in clay.”

But in graduate school at NDSU, pottery took a back seat to computational chemistry. “I spent my days researching the electronic structures of quantum dots and organometallic complexes,” he says. “I didn’t have time to ‘play in the mud.’”

In 2016, Lystrom moved to Los Alamos for a summer research position, and pottery remained on hold as he focused on building a scientific career. It wasn’t until he returned to the Lab as a postdoc that a colleague suggested he check out the Fuller Lodge Art Center’s Clay Club. “I joined in December 2023,” he says. “Since then, I’ve been throwing.”

Balancing science and art

Lystrom estimates he spends 10 hours a week in the pottery studio, though much of that time is now dedicated to teaching beginner classes. “I love helping people with their throwing techniques,” he says, noting that teaching has made him more patient and adaptable. “To be an effective teacher, you have to approach problems from multiple perspectives.”

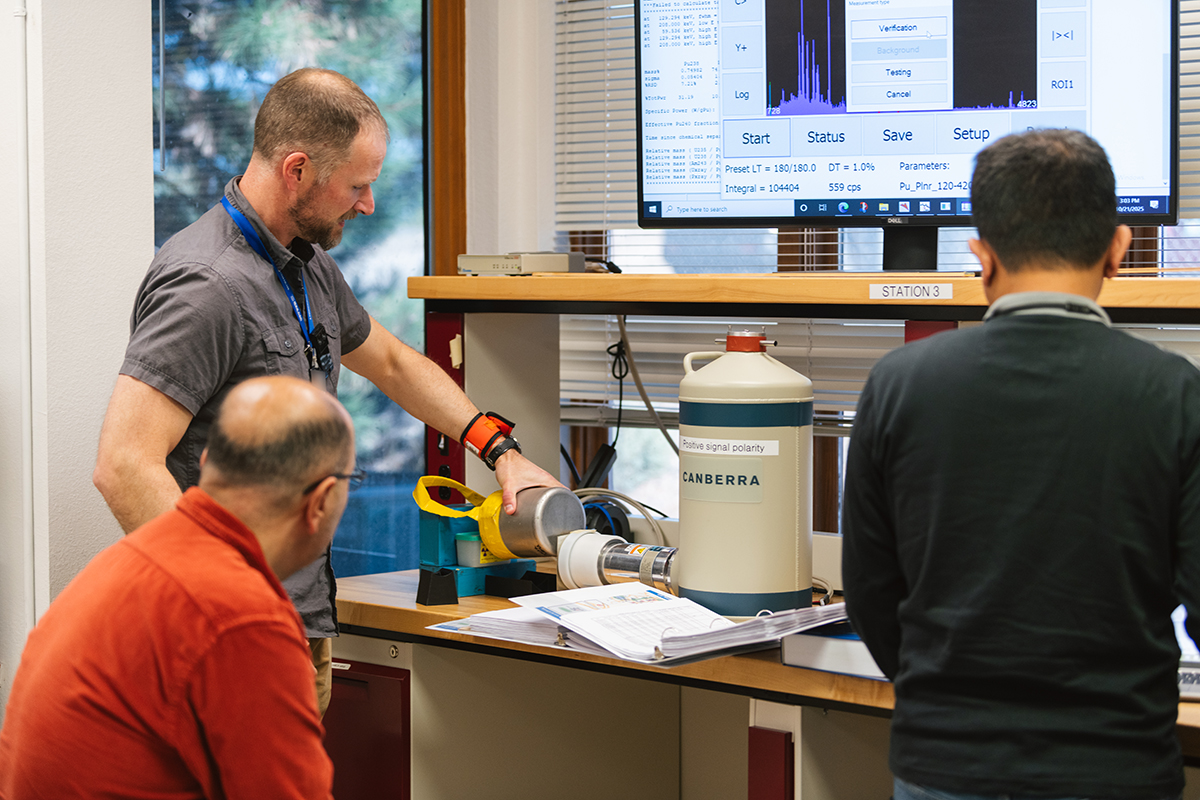

That mindset has also benefited his work at Los Alamos. As a staff scientist in the Lab’s High Explosives Science and Technology group, he studies the behavior and performance of high explosives, which are used in many national security applications. “My workdays are multifaceted,” he explains. “I design, model, and field explosive experiments in collaboration with colleagues across the Laboratory.”

Whether in the lab or the pottery studio, Lystrom finds that both disciplines demand creative problem-solving. “Out-of-the-box thinking is key,” he says.

Yet, perhaps the most important lesson he’s learned from teaching pottery is a practical one: “My students take home the pottery,” he says, “So my house doesn’t overflow with more than it already has.” ★