Engineering in the national interest

Los Alamos and Sandia national laboratories collaborate to support the nuclear security enterprise.

- Jake Bartman, Communications specialist

Although engineering is an essential part of Los Alamos National Laboratory’s work, only one “engineering laboratory” exists in the nuclear security enterprise, and that is Sandia National Laboratories.

That’s because Sandia, which has primary locations in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Livermore, California, is responsible for designing the nonnuclear components of the nation’s nuclear weapons. Around 6,300 of the approximately 6,500 parts in today’s weapons were designed at Sandia.

“Sandia is very much focused on engineering,” says Rita Gonzales, who is Sandia’s deputy laboratories director for nuclear deterrence and chief technology officer. “I’d say that Los Alamos is focused more on physics with a little bit of engineering, and we’re probably the opposite of that—we’re mostly engineering with a little bit of physics and other science critical for our component work.”

Sandia began as part of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos but split off after World War II, becoming a partner laboratory in Albuquerque with more room and improved proximity to what is now Kirtland Air Force Base. Today, Los Alamos and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory are responsible for designing and engineering nuclear weapons’ physics packages—the part of a weapon that uses high explosives and special nuclear material to create a nuclear explosion. However, a nuclear explosives package can’t be deployed as a weapon without the nonnuclear components that Sandia develops, making Sandia’s role a unique and vital one within the nuclear security enterprise.

In addition to designing weapons’ nonnuclear components, Sandia is the lead systems integrator for each weapon system. Sandia works with the U.S. Department of Defense to ensure that weapons are compatible with delivery systems (such as missiles and airplanes), and Sandia also ensures that each system’s physics package functions with every other component. “We work closely with Los Alamos to negotiate requirements,” Gonzales says. “We have to understand what Los Alamos needs from the physics package—its optimal capability—and we collaborate to get that system to function.”

To deter the United States’ adversaries, a nuclear weapon must be safe, secure, and effective. That means that the weapon must perform reliably after exposure to conditions such as heat (after sitting beneath a plane on a hot runway) or cold (after arcing into outer space). The weapon must also detonate only when it’s supposed to.

As the designer of the arming, fuzing, and firing systems that make nuclear weapons usable, Sandia takes the lead on developing the safety and security systems that keep weapons from being detonated by accident (such as in a plane crash) or without authorization by the president of the United States. Gonzales says that this process is collaborative, however. For example, in January 2025, the National Nuclear Security Administration, which oversees Los Alamos, Livermore, and Sandia, completed the last production unit for the B61-12 life extension program (LEP). This program lengthened the life of the B61-12, a nuclear gravity bomb that entered service more than half a century ago, by 20 years.

During the B61-12 LEP, Los Alamos and Sandia worked together to design the system’s safety and security architectures. “We looked at various accident scenarios and at various conditions to ensure that there wouldn’t be any accidental nuclear yield,” Gonzales says. “That takes both our laboratories to accomplish. It’s a real partnership.” The laboratories are currently partnering on another iteration of the B61: the B61-13.

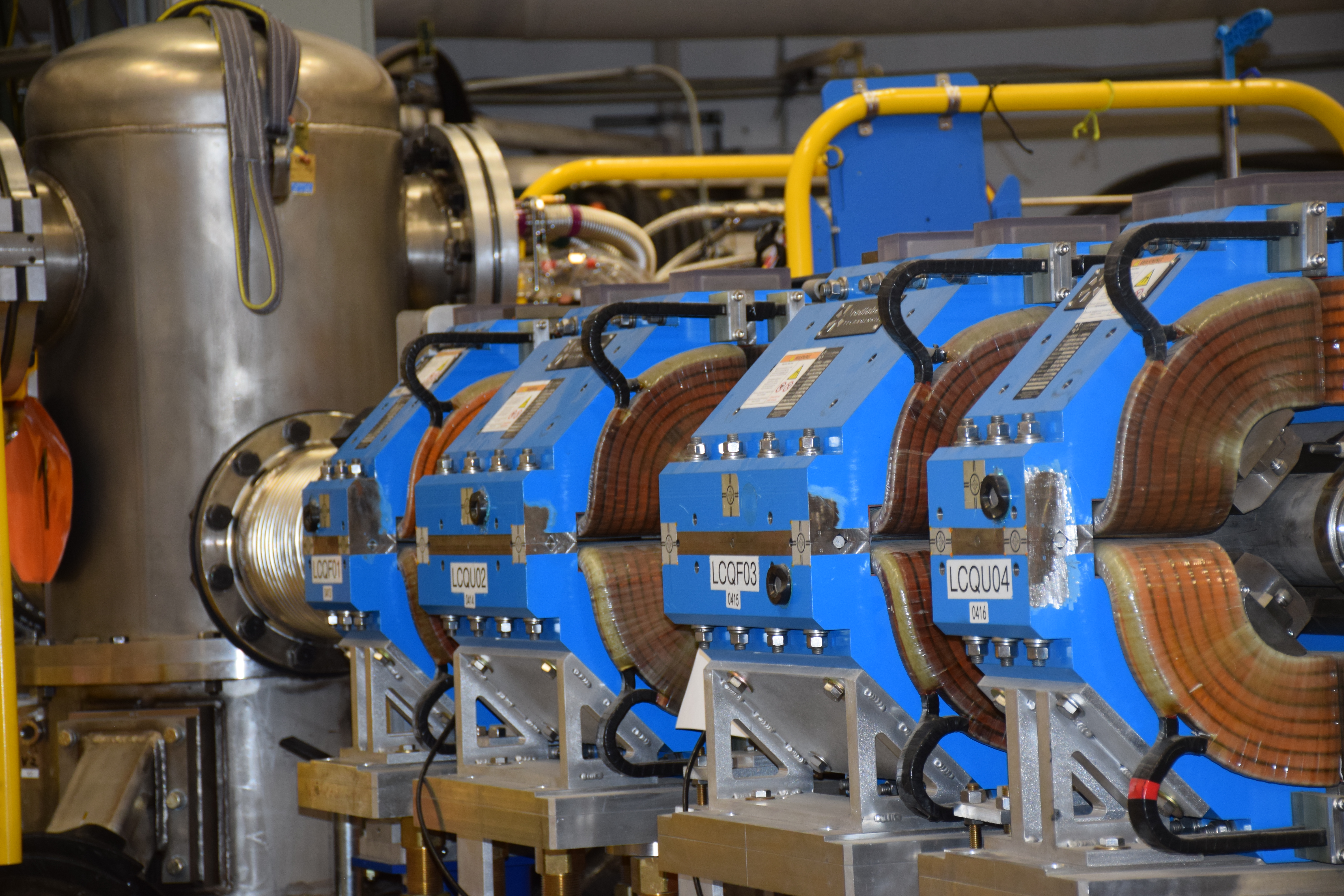

The proximity of Los Alamos to Sandia’s main location in Albuquerque—the laboratories are less than two hours apart—supports this partnership. Scientists from Los Alamos often make use of Sandia’s Z machine, which is the world’s most powerful pulsed-power facility and x-ray generator, and researchers from both laboratories collaborate on experiments at Los Alamos’ Dual-Axis Radiographic Hydrodynamic Test facility, which images imploding weapon components.

Gonzales says that the nuclear security enterprise benefits from the redundancy of certain tools, such as blast tubes (which are used in explosives testing) and centrifuges, at the two laboratories. “When one site is at capacity, we can easily go to the other, and that happens both ways,” she says. “That’s good for keeping programs on schedule.”

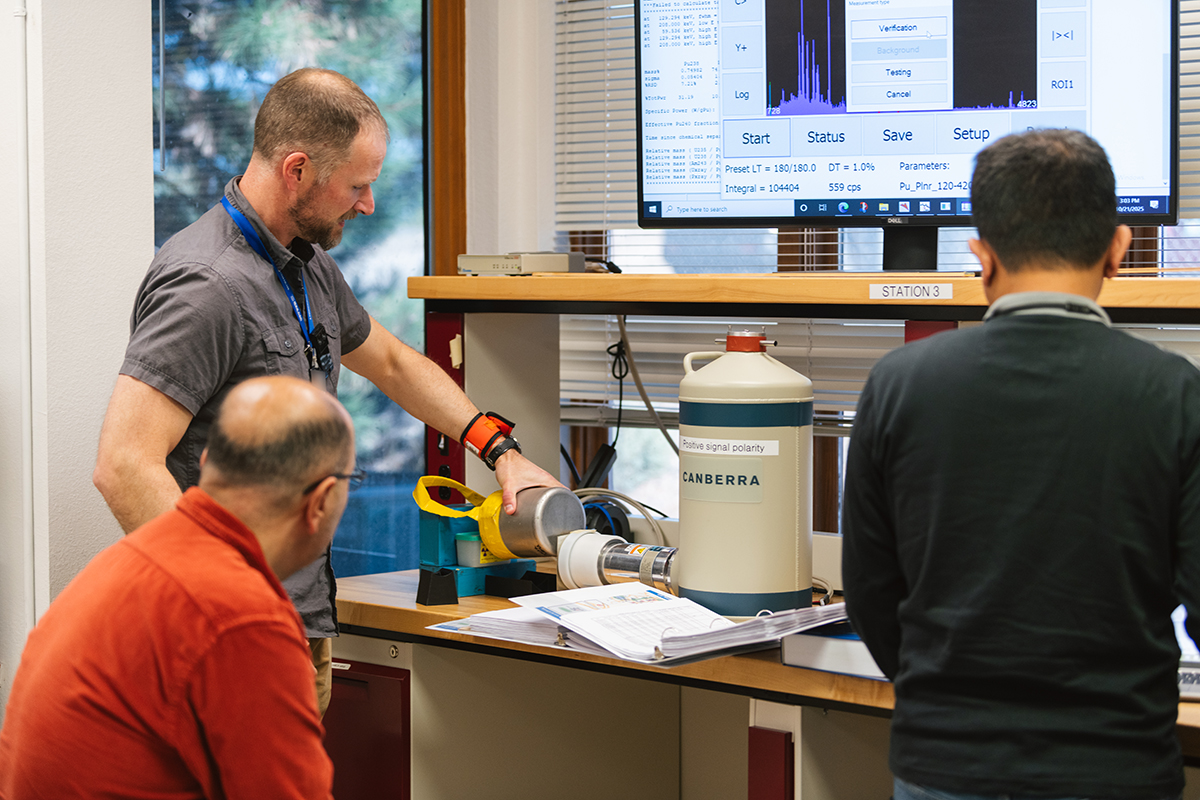

Los Alamos and Sandia also support each other during the annual assessment process. This process, which comprises evaluations by each laboratory of the state of the stockpile, requires the laboratories to share data from their weapon surveillance programs.

To ensure thoroughness and accuracy, as part of their annual assessments, the laboratories conduct peer reviews by challenging each other’s findings. And yet, it is indicative of the close relationship between Los Alamos and Sandia that oftentimes, both laboratories arrive independently at similar conclusions.

“Usually, each lab has something unique at their site or within their areas of responsibility, but there is also quite a bit of overlap on the themes of what folks are seeing and what they’re concerned about,” Gonzales says. “We each have distinct roles as part of the annual assessment, and we draw on each other’s unique expertise and capabilities.” ★