A critical crew

Behind every subcritical experiment is an army of people and years of work.

- Jill Gibson, Communications specialist

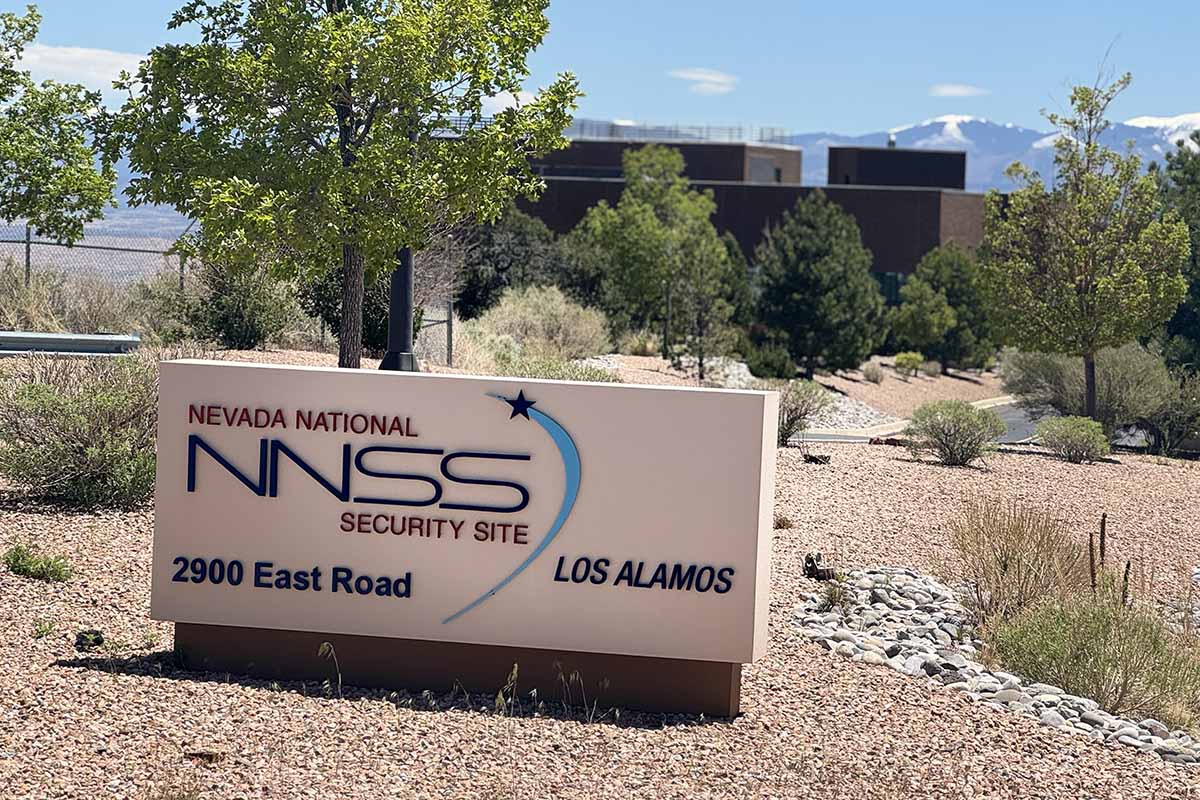

Carrying out a subcritical experiment requires hundreds of people and extensive collaboration and coordination. Every test brings together experts from across the nuclear security enterprise.

At Los Alamos National Laboratory, numerous people work behind the scenes for years leading up to each test series.

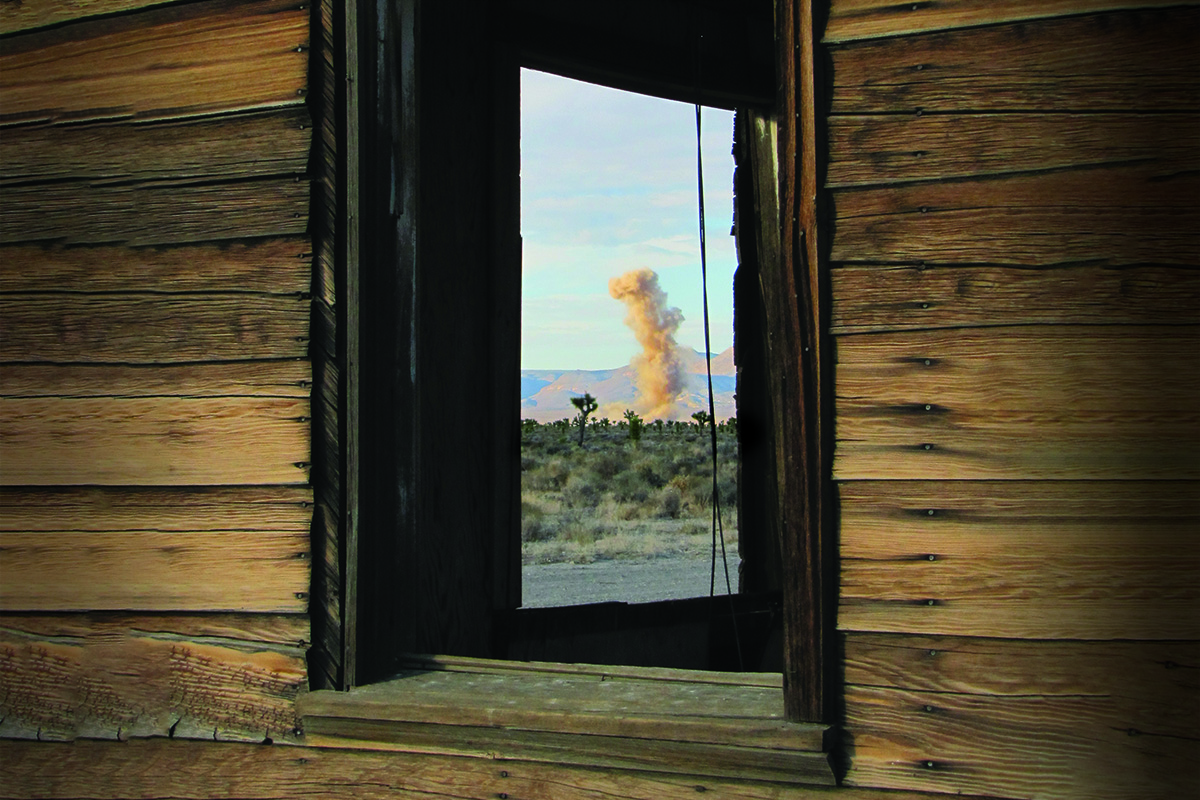

Hundreds of scientists, engineers, and technicians design, develop, and manufacture the devices, diagnostics, and experimental platforms for each subcritical test. In Nevada, miners, electricians, pipefitters, inspectors, and many others contribute to building and maintaining the state-of-the-art subterranean facility where subcrits are detonated.

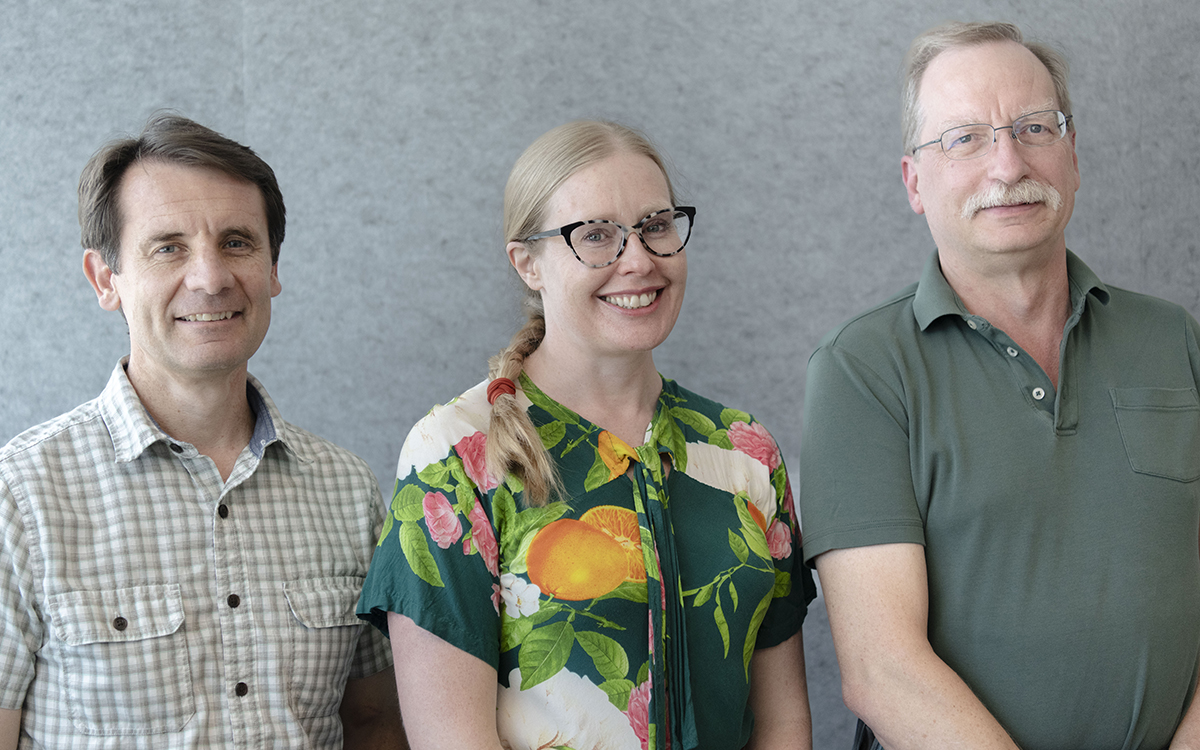

It's difficult to capture the intense time, effort, and expertise that goes into these underground tests in Nevada, but three important roles in each subcrit are the test designer, the test director, and the diagnostic coordinator. The people in these roles can change from test to test, but National Security Science was able to sit down with the three people involved in an upcoming subcrit.

Meet the designer

Los Alamos physicist Candace Joggerst designs weapons primaries—the first stage (which involves fission) of thermonuclear devices. Her goal is to create weapons systems that address specific requirements, function properly, are cost effective, are fast, and are easy to manufacture and produce. “Today’s threat environment is radically different, so we must be ready,” she says.

Joggerst uses high-fidelity computer codes to create her designs, but she needs real-world data to ensure the devices will perform as predicted. That requires testing, which in this case means subcrits. “We can put every other component of a weapon through its paces, but a subcrit is the only way to push the plutonium in the way a nuclear detonation would. We need this data, and the only way to get it is through subcritical experiments. We have no other opportunity.”

So, when Joggerst was offered the chance to design a subcritical experiment to test one of her primary designs, she quickly replied, “That would be awesome.” Although she has worked on many subcrits, an upcoming test, planned for early 2026 using the Cygnus test bed, will be the first time she has put one of her own designs through its paces. She says no two subcrits are exactly alike. “Every experiment is its own special snowflake.”

For Joggerst, the data will be invaluable. “My job is to answer questions about how the device operates, the impact of aging plutonium, safety and surety, how the systems work together in real life conditions, and more. When it comes to answering questions, there is no substitute for actual data.” She adds that designing an experiment to produce the much-needed answers is challenging. “A nuclear device involves complex, tightly integrated components. It’s not Garanimals,” she says referring to the mix-and-match children’s clothing brand that helps children dress themselves because they can pair any top with any bottom. “It’s all coupled systems, and you must design and test in an integrated way.”

During the week leading up to the test and the actual experiment, Joggerst says she will be in Nevada, “showing my commitment but trying not to get in the way. Data will be available almost immediately. We’ll know right away if something unusual is happening,” she says.

Joggerst describes the upcoming test as “super exciting and also terrifying” because of the time and effort she and her colleagues have devoted to designing and building the experiment. “My hands are sweating just thinking about it and about all the people who have worked so hard to get us to this point. The machinists, the engineers, the diagnostics team… everyone works together.” She says the test will provide critical information for potential systems and build capabilities for future tests.

Meet the test director

Los Alamos engineer Stephen Sintay spends a great deal of time in Nevada. That’s because Sintay is the test director for a series of subcritical experiments that will kick off in early 2026. He says he’s been preparing for the test series since 2018, and things are moving fast. “There’s lots of momentum,” says Sintay. “I can see that across the project.”

The first in the upcoming series of five subcritical experiments will be executed in the Cygnus test bed, while the other four will take place using ZEUS, which is currently under construction. Three other nonnuclear experiments will be conducted in Los Alamos. These experiments will use surrogate materials that mimic the behavior of nuclear components to prepare for the subcritical tests.

As test director, Sintay is responsible for multiple moving parts that include everything from getting the facility ready and integrating schedules to preparing the actual device. “One of the test director’s jobs is to demonstrate compliance with all rules and regulations governing a nuclear facility,” Sintay says. He must understand who is responsible for fulfilling compliance elements and providing evidence that requirements have been met.

Sintay describes the actual test day of a subcrit as “very choreographed.” “We will have lots of practice runs, and I will be playing an actual directing role,” he says. “On the day we insert the device into the facility, all the multiple project elements will converge.”

Sintay notes that one of the last things that will happen before the test is executed is connecting the diagnostics. “The team will be hooking hundreds of fibers together and testing every one of them.” Diagnostics preparation often takes weeks, according to Sintay. “The objective is to get nanosecond precision on every signal.”

Sintay says this series of experiments is crucial. “The series will establish a baseline to characterize how weapons design changes nuclear behavior,” he says. He points out that the ZEUS test bed will allow scientists to evaluate the nuclear performance of plutonium and examine when it achieves criticality.

“This series will generate a data set that will reduce uncertainty and generate new lines of inquiry,” says Sintay, adding, “I’m excited and nervous. The data will be spectacular.”

Meet the diagnostic coordinator

“Diagnosticians are the providers of ground truth,” says Los Alamos physicist Chris Frankle. Frankle is the diagnostic coordinator for an upcoming series of subcritical experiments that will take place at PULSE. “Diagnostics is the end of the chain,” Frankle says.

There are about 100 people on Frankle’s diagnostic team, and his work involves collaboration amongst multiple entities. “Once we are underground, you can’t tell which people are from where,” he explains. “We are very much an integrated team.”

Frankle says a typical subcrit may have 10 different diagnostic systems and several hundred channels of incoming data. “Diagnostics demands a great deal of preparation,” he says. “Part of my job is to be meticulous.”

Frankle’s attention to detail has paid off. He worked on his first subcritical experiment in 2001 and has developed his expertise over the decades. “You have to be sure when you go into the final countdown that things will work,” he says, adding, “Our track record is very good at returning data.”

Another of Frankle’s roles as diagnostic coordinator is to play referee, because the vessels that confine the experiments and the test beds themselves have a finite amount of room for diagnostic equipment. “Everybody would like to have a spot, but you can only fit so many probes, so ultimately I decide on the best diagnostic suite to meet the requirements of the designers,” he says.

Frankle says in many ways subcrits resemble the full-scale underground tests that once took place in Nevada. “There is definite overlap with the types of diagnostics and skillset, but our technology has changed.”

He emphasizes that the main similarity is that subcrits provide real-world data. “Subcrits take away the guesswork and give scientists actual measured data to prove whether their computer codes are correct,” he says. “In diagnostics, our job is to measure performance, to get that information from the test.” ★